Where is the truth in the homelessness crisis?

Shannon Badiee via wikimedia commons

Under the freeway, homeless tents are lined up in San Francisco.

February 2, 2023

As a Bay Area kid, tell me if these experiences sound familiar: walking across Civic Center and seeing mentally ill persons at every corner; waking up in the middle of the night to ravaged screams and shaking gates; watching druggies shoot up heroin while grabbing a bagel.

Homelessness is an issue. Full stop. It hurts people who aren’t homeless, it kills people who are. Nobody questions that it’s a crisis, and nobody even questions what to do about it.

Yet despite the homelessness crisis worsening year after year, homelessness seems to always be addressed in the same way: more soup kitchens, more public services, more low-income housing, more aid for homeless people right here, right now.

But the reality is homelessness cannot be solved by simply soup kitchens or rent control because homelessness isn’t an issue of the government or the people; it’s a reality of space.

Before you blame the failures of our cities to address homelessness, consider one thing beyond the systemic or immediate issues facing homeless people today: what is the root of their problem? Simple: they can’t afford rent.

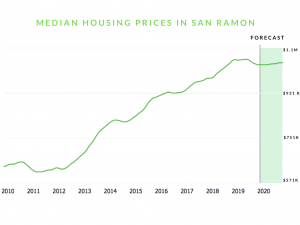

Yet, rent prices aren’t as extreme as some people make them out to be. Sure, the average rent listed on Redfin for an apartment in San Francisco is $3,340 a month. In Los Angeles, $2,043 a month. But in Sonora, the average rent is $892 a month. In Independence, it’s $935 a month.

Those cities didn’t enact rent control. They didn’t suddenly and magically solve the supposed “high prices” of rent in California by fiscal responsibility. They did so because the invisible hand of the market dictated the prices of rent in Sonora and in San Francisco.

These illustrate the undeniable reality that rent isn’t something to turn with knobs and dials, it’s a reflection of the reality around us.

If the market lists a two bedroom apartment in San Francisco for $4,000 a month, then that means the value of that real estate is $4,000 a month. Controlling rent or adding more housing doesn’t change that fact, and it won’t improve people’s conditions. No, what it says is that people can’t afford to live in San Francisco, and that they can afford to live in Sonora.

San Francisco is an island seven miles long, seven miles wide, and we expect it to fit 815,000 residents? No amount of rent control can fix the hard truth: San Francisco isn’t big enough to fit everyone.

So if the market has decided that rent should be $3,340 a month, and people can’t afford that, then they have to move. Move to places with less people, with starving economies, with lower rent. Live in places they can afford to live, who would’ve thought that? Yes, the problem with homelessness isn’t homeless people or failing governments, it’s a problem of the rural and urban divide.

In every county in California, as the lowest average rent increases, the number of homeless people in that county increases. There’s nothing complicated to it; as rent prices increase, the number of homeless people increases. But again, that’s not an indictment of rent control or failing zoning on the government’s part, it’s an indictment of people’s expectations.

The notion that cities ought to accept the hefty price tag associated with the homelessness crisis for improving their real estate market and their economy is ridiculous. And it’s ridiculous to expect that for their marked economic successes, they are expected to support an ever-growing homeless crisis. No, the expectation should be that they create the best economy possible, and those who can’t afford to live there, ought to live somewhere else.

California isn’t a collection of cities on the brink of collapse, it’s an odds and ends spectrum with San Francisco and Los Angeles on one side, and Tracy and Woodland on the other. These smaller counties and towns, rural in nature and spread thin in their economy, are desperate for immigration. It’s why they rely on it, in fact, because there aren’t people who actively want to live there.

But why should that be the case? Why should it be the case that everyone wants to and tries to squeeze into these seven mile long, seven mile wide islands of overpopulation? Why can’t it be the case that people who can’t afford to live in San Francisco live elsewhere?

The data is clear on this. As you increase population density for each county, the number of homeless people increases. Sure, population density correlating with increasing homeless people is because of responsive rent prices, drug addiction and ignorant city governments. But those are only because of the strain of supporting impossibly large cities.

These megacities can’t and shouldn’t be expected to support all of California’s homeless on their backs, and these rural communities can’t be expected to die on the vine, struggling each day for labor and companies to finance their cities while city dwellers complain of overpopulation and too many big corporations hogging up their land.

These homeless people deserve the opportunity to live in areas that want them and to be offered jobs that suit their needs. And if there were enough low skill jobs for homeless people in these megacities, then why would there be so many homeless people?

In the tech capitals of California, what role is a homeless person, without proper education and without the proper skillset, supposed to play in a white-collar office? That’s a question megacities will refuse to answer, but abandoned rural communities will offer readily: as a thriving member of their community no matter their background.

The reality that homeless people exist in, as well as the roots of their predicament, are staring us right in the face. Instead of moralizing the lives and harsh economic realities of homeless people, let’s take a step back from our privileged properties and consider what we can actually do to help others.

Don’t assume like always that others have the same privilege as you. That homeless people, if only they had the right rent control or mental illness support, could suddenly button up their suits and work at Citibank or Salesforce. That if only the government did more, we could all cram into San Francisco with the same living conditions and live perfect lives. For once, I plead to both sides, consider what we can actually do, what is actually happening, and why it’s actually happening.