San Ramon housing crisis prices teachers out

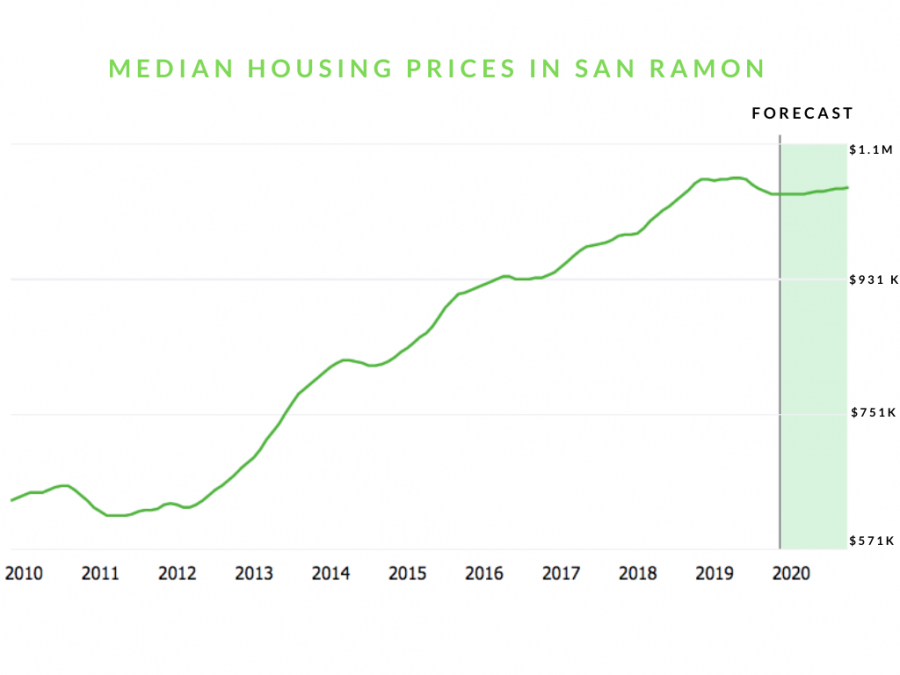

Since the 2009 housing crash, prices have skyrocketed, with median house market value forecasted to reach $1.05 million in January 2020. Data from Zillow.

December 6, 2019

Former Dougherty Valley High School math teacher Mr. Colin O’Haire spent the first nine years of his teaching career in San Ramon. Yet as rent increased, he and his wife, who also taught in San Ramon, struggled to find a comfortable house for their growing family — even on two full-time teacher salaries.

Ultimately, O’Haire moved to Rocklin High School in 2019, where he bought a home at a fraction of San Ramon’s housing prices.

O’Haire’s story is far from unique. An escalating San Ramon housing crisis is driving away Dougherty teachers, whose salaries cannot match skyrocketing market prices.

Impact on DVHS teachers

While unaffordability of housing in San Ramon for teachers has long been an issue, the problem has accelerated recently. In Oct. 2009, the median sale price of a house in San Ramon was $592,000, according to data from Zillow. Now, a decade later, this figure has skyrocketed to $985,000.

Since 2017, multiple tenured DVHS teachers across various departments have left the school.

Ms. Julie Lazar, a former DV history teacher who currently teaches at Vista del Lago High School in Folsom, California, cited her and her partner’s desire to own a home as her primary reason for leaving DVHS in 2018. While at DVHS, Lazar rented an apartment in Walnut Creek, but rising rent costs left her unable to save for a down payment on a house in the San Ramon area.

“Every year the rent would go up by $200 … and with housing prices [in the Bay Area] … to put even a 10% down payment is almost insurmountable on a teacher’s salary,” Lazar said.

In addition to teaching at DVHS, Lazar tutored students and drove for DoorDash Inc. to generate extra income. However, even with multiple jobs, Lazar was unable to accumulate a down payment, eventually spurring her move to Folsom, where she was able to buy a house for almost half the price of East Bay homes.

Ms. Dana Pattison, another former DV history teacher who now teaches in Bellingham, WA, echoed Lazar’s concerns, which also caused her to move in 2018.

“I wanted to own my own place. And as a single teacher that’s not possible … even to rent a one-bedroom apartment in San Ramon is $2,300 a month, which is more than half of my paycheck,” Pattison said.

Pattison, who had lived in California since her childhood, feels that her inability to pursue her passion in teaching and buy a comfortable home in the East Bayhas jeopardized her right to the American Dream.

“I’ve been robbed of this American Dream access, where no matter what I do, I can’t get the home,” she reflected.

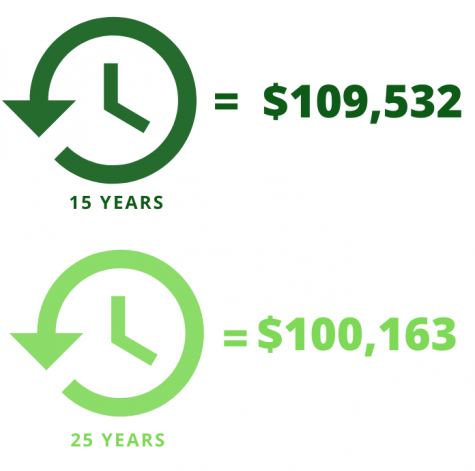

While Pattison understands that housing unaffordability in the Bay Area has been exacerbated by market conditions, she still believes it is partially perpetuated by the way the SRVUSD teacher salary schedule is set up. Currently, teachers with a master’s degree and 75 additional teaching units, which they can gain through various teaching courses and workshops, reach a maximum pre-tax salary of $100,163 after 25 years of teaching. Additionally, while teachers can move up the salary schedule by earning additional credentials such as master’s degrees, they often need to pay thousands of dollars out-of-pocket in tuition or fees to acquire such credentials.

The salary schedule for teachers dramatically differs between SRVUSD and other school districts, with teachers at Bellingham Public School District making $109,532 in 15 years, while teachers in SRVUSD make $100,163 after 25 years.

However, Pattison feels that teachers should be able to reach the maximum salary sooner, considering the living costs in the Bay Area. In the Bellingham Public School District, where she currently teaches, teachers are able to reach the maximum pre-tax salary of $109,532 after only 15 years of teaching.

Pattison believes that decreasing housing costs for teachers ultimately needs to start with the City of San Ramon and SRVUSD collectively outlining a variety of possible initiatives, including government subsidized loans, negotiations with builders for teacher-specific housing and increased salary compensation.

Mr. Robert Gendron, a co-lead negotiator for the San Ramon Valley Education Association (SRVEA) and DVHS mathematics teacher, agrees. Specifically, he believes that SRVUSD should increase salaries for teachers, especially since current salary increases do not match inflation rates and cost of living increases.

Gendron also feels that SRVUSD could afford to pay teachers more if they tapped into the unrestricted reserve section of the annual budget, which is meant for discretionary usage by the district. Although SRVUSD has cited the importance of maintaining robust reserves in case of an economic downturn, Gendron believes that SRVUSD’s unrestricted reserve percentage of 18% demonstrates excessive fiscal conservativism.

Gendron explained, “We had an economic downturn in 2008. And during that time, [SRVUSD] was asking for furlough days from teachers, which means we don’t go to work and don’t get paid … During that time, [SRVUSD’s] reserves increased. So the money that they had to spend when things were down, they didn’t even spend.”

However, O’Haire understands that some of the issue is out of SRVUSD’s control.

“They could have met us more toward what we wanted … And made things more tangible. But the housing prices they don’t have control over.”

He also agrees that SRVUSD has given teachers commendable benefits packages, especially compared to other districts in the state.

“[SRVUSD health benefits] are a good amount of money. [My wife and I] in our new district, pay $500 a month for benefits versus free [in SRVUSD],” he explained.

Still, he maintains that higher salary compensation is possible.

“It’s really heartbreaking to have to leave a place that you love [due to unaffordable housing] … And it’s so exhausting when you’re doing such a human, personal job, but you’re treated like a line item,” O’Haire expressed.

Educator housing assistance in Bay Area school districts

Many Bay Area cities and school districts have recognized the unaffordability of local housing and thus created initiatives to mitigate the burden on teachers.

Santa Clara Unified School District, for example, built an apartment complex for teachers, Casa del Maestro, to address the rising housing prices in the area.

According to EdSource, “Rents for the 72 apartments [in Casa del Maestro] are about 80% of market rent, between $1,430 for a 722-square-foot one-bedroom unit to $2,195 for a 1,170-square-foot two-bedroom, two-bath unit.”

Additionally, San Francisco Unified School District has instituted a program known as Teacher Next Door. According to the San Francisco Mayor’s office, through this program, eligible teachers in the district qualify for loan assistance from the district for their first home, which provides $40,000 to teachers for a market rate unit, or $20,000 for a below-market-rate unit. Additionally, the loan is forgiven for teachers after 10 years, given compliance with all program requirements.

Recently on Nov. 5, San Francisco voters also passed a $600 million affordable housing bond, some of which will go directly to building affordable housing for educators.

In addition to these developed programs, various other Bay Area school districts similar in composition to SRVUSD have taken action on teacher housing, including West Contra Costa Unified, Mountain View Whisman School District and the Sonoma County Office of Education.

SRVUSD perspective

Insufficient funding from the state has caused SRVUSD to struggle to balance their expenses, including matching teacher salaries to cost of living increases.

“Funding from the state doesn’t keep up with our actual expenses,” Daniel Hillman, Director of Facilities Development at SRVUSD, stated. “[We have] to balance the books, meaning covering all of our expenses and our [previous] commitments to employees.”

In response to low education funding, Proposition 98 was passed in 1988, which mandated that a 40% minimum of the state’s general fund be spent on K-12 and community college education. Despite its passage, education funding has remained an issue.

“Before [Proposition 98] went into effect, it was seen as this minimum that we’re going to spend on education. But what it’s actually paradoxically turned into is this maximum,” Hillman explained.

A 2017 report from the California Legislative Analyst’s Office found that since the passage of Proposition 98, K-12 funding, adjusted for changes in enrollment and inflation, has not changed significantly from 1988-1989 levels.

“It isn’t just that the state is short on money, it’s that they don’t have a commitment to fund education to our actual expenses. They have a system set up to fund education to a certain level, and they do that. But that’s not the true cost of what it takes to do business,” Hillman continued.

Regarding the growth in the district’s reserves during the 2008 economic downturn as cited by SRVEA, Hillman clarified that SRVUSD was actually forced to tap into their reserves after an unexpected mid-year cut in revenue from the state. However, after receiving funds from the federal government through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, SRVUSD invested some of that money back into the reserves to protect against future cuts, resulting in the observed increase in unrestricted reserves.

SRVUSD also attributes varying regional salary schedules to differences in negotiations between individual districts and their respective teacher unions. Although SRVUSD’s salary schedule increases more slowly compared to nearby districts, it provides nearly $25,000 in benefits to its employees, spending $102,200 on teacher salary and benefits on average per capita, which is greater than similar school districts.

“[When you get more funds] you use the money and you negotiate with the teachers union to figure out how those dollars will be spent in the district,” Hillman said. “[Salary, benefits and salary schedules] are trade-offs. Neither decision is good or bad; it’s just the local decision.”

Due to teacher input, SRVUSD has recently considered affordable housing initiatives, such as a teacher housing bond, and is currently in the process of gauging community interest. SRVUSD expects to receive the results from their research by early spring of 2020.

Furthermore, although they have not reached out formally, SRVUSD is open to potentially partnering with the City of San Ramon and the Town of Danville to outline such initiatives.

SRVUSD Chief Business Officer Greg Medici reaffirmed that despite financial constraints, the district is committed to its teachers and students.

“We know we have a lot to accomplish, but everything we do is for [teachers and students,]” he said.

An introduction to San Ramon affordable housing

In San Ramon and beyond, affordable housing is becoming an increasingly prevalent issue. A 2019 EdSource analysis found that “in 47 school districts in [the Bay Area], the highest-paid teachers only earn enough to rent an affordable one-bedroom apartment, using the federal definition of affordable housing as 30% or less of household income.”

Cities have tried to increase affordable housing through Inclusionary Zoning policies. These laws mandate that a certain percentage of units built by contractors be set aside for affordable housing, which are then distributed to low-income residents by local governments on a discretionary basis, as long as state guidelines are met.

Affordable housing is also promoted through the Regional Housing Need Allocation (RHNA), a state-wide mandate overseen in the Bay Area by the Association of Bay Area Governments. RHNA sets general housing quotas that cities must meet and creates specific income categories that each require a certain number of units built. These categories are based on the area median income of that region, with extremely low income, very low income and low income individuals making 0-30%, 30-50% and 50-80% of the area median income, respectively.

In Contra Costa County, with a relatively high area median income of $111,700 per year, public workers such as teachers may automatically qualify for affordable housing by falling into the low income or very low income categories. However, as teachers stay in the district, they earn more and move out of the low-income brackets, removing their eligibility for rent assistance and low income housing. Consequently, greater experience in the district does not guarantee an increased ability to afford housing.

City of San Ramon perspective

Another avenue for promoting affordable housing for teachers is through the City of San Ramon, which oversees local housing policies and is tasked with meeting the city’s RHNA, which the city fulfills by creating zoning plans that meet the quotas for affordable housing.

According to Deputy City Manager Steven Spedowfski, San Ramon’s plans are in compliance with the current RHNA cycle, which requires 795 very low or low income units from 2014-2022. However, as the city only approves housing developments, rather than building them, the onus is ultimately on developers to construct units. As of 2017, only 102 of these units have been created. Spedowfski explained that market forces such as high land and labor costs discourage construction, and while the city can incentivize development by decreasing building fees, its ability to do so is limited.

“[The city] goes after fees, but it charges those fees in order to recuperate the cost for providing services to the homes,” Spedowfski said.

As for housing initiatives such as San Francisco’s Teacher Next Door program and Santa Clara’s Casa del Maestro apartment complex, Spedowfski said that to his knowledge, the city council has not yet proposed similar programs. San Ramon’s ability to replicate these programs is also constrained by the low property tax and sales tax revenues that fund their budget.

“We have a very low business license fee to retain and attract businesses, and with our limited sales tax base, we receive about $9 million to $10 million a year in sales tax revenue,” Spedowfski said, citing higher such revenues in neighboring cities such as Pleasanton and Livermore.

Spedowfski added that the city’s tax revenue is also limited by Proposition 13. The 1978 California measure mandates that property taxes for homes and businesses only be reassessed when they are sold, effectively freezing property taxes for some businesses at 1970s levels. It also requires local tax increases to be approved by two-thirds of voters, making it difficult to raise revenue.

“Santa Clara and San Francisco have so many jobs and their revenues are far higher. In San Ramon, a program like that, with the cost of living here and our budget … you might be able to do something very small, but it wouldn’t be a noticeable impact,” he said.

However, while large scale housing assistance for teachers may presently be out of San Ramon’s reach, future changes could alleviate some of the burden. In June, the city designated a company known as HouseKeys to administer their affordable housing program. HouseKeys determines the eligibility of residents for affordable housing and conducts orientations about the application and lottery process.

Additionally, according to Communications and Engagement Analyst Simone Finney, the city is working with housing developer Lennar to develop Priority Preference criteria that would give public workers, like teachers, additional weight in choosing affordable housing. In affordable housing lotteries, all entrants have equal chances of being selected, and of those selected, those with Priority Preference will have weighted choice of the units. These new criteria are expected to be adopted by spring 2020.

Planning is also underway for the development of 4,500 units in Bishop Ranch, 15% of which would be demarcated as affordable.

“The city is looking into densifying our core — denser apartments that go upward instead of outward. When you have more units coming in that are within that [income] level, those are units that a teacher can look at,” Spedowsfki said, although he acknowledged that the units would only be rentals.

Finally, a ballot measure to overhaul Proposition 13 to reassess businesses’ property taxes every three years is on the ballot for the 2020 election. If approved, the change would raise $11 billion in revenue per year, mostly going to public schools and local governments, and could infuse the city with new capital that could expand its affordable housing capabilities.

Looking forward

As housing prices continue to soar, affordable housing for teachers and teacher turnover at DVHS is likely to remain a challenge for years to come. Alleviating this crisis will require cooperation between all relevant parties, including SRVUSD, the City of San Ramon and local teachers.

However, teachers remain optimistic about progress on the issue.

“It does take refocusing priorities, but it can clearly be done,” Pattison expressed.