Feeling like a cultural “outsider”: three perspectives

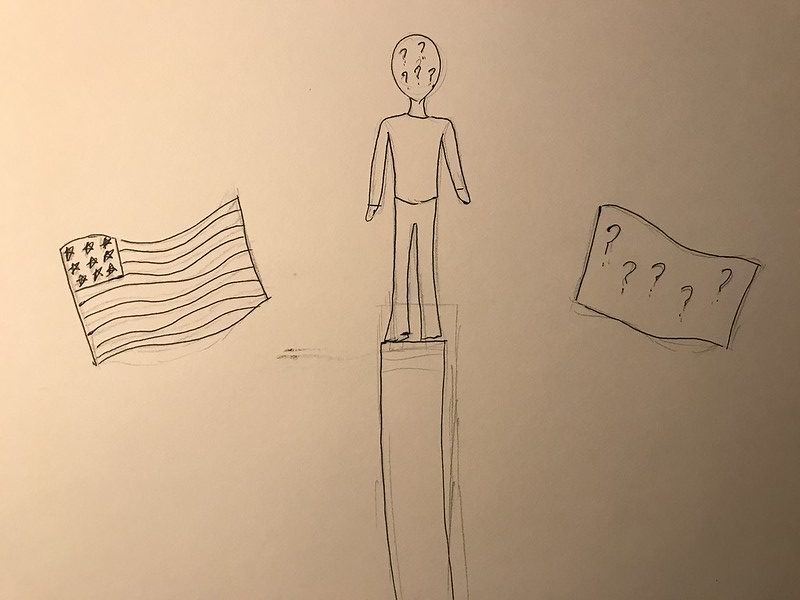

Having multiple cultural identities can lead to an internal struggle.

June 9, 2022

Second-generation Americans, U.S.-born residents with one or more foreign-born parents, often struggle with feelings of alienation from both their ethnic heritage and American culture. Distraught with clashing identities, we struggle to find groups we can belong in, despite, ironically, being a part of multiple cultural groups.

Dougherty Valley High School has a vibrant community with students and staff who struggle with their cultural identities. According to a poll conducted by the Wildcat Tribune, 74% of respondents felt like an outsider in their own culture.

Despite all three of us (the writers of this article) being second-generation Indian Americans who currently live in the same city, we hope to explore different aspects of what being “Indian-American” means to us by sharing our own experiences.

Nayja’s Anecdote: To be or Not Be “Indian Enough”

“Oh, they’re American.”

Scorn masked with a knowing look. Our Indian cousins’ tone said it all. The moment my sister and I broke out into an English conversation amidst a discussion with our cousins during a visit to Mumbai, India, they assumed us uncultured, for the American accent was perfect evidence of our torn roots. We were something else: not Indian, definitely not Indian, at least, to them.

They continued to speak Hindi, my mother tongue, with a hint of slang supposing we wouldn’t understand. And we stayed silent. Smiling and silent.

I couldn’t tell them that our first language was Hindi, not when I was afraid that a hint of my American accent would slip through. If my tongue slipped, if my r’s rolled a little too softly and my mouth forgot to enunciate every syllable, it would be concurrent to telling them, “Yes, we’re American … We’re the same Americans you see in the movies, arrogant and uncultured.”

During my family’s visits to India, sprinkled among the delightful experiences I enjoyed were such similar scornful encounters where people thought I wasn’t Indian enough. These moments stirred feelings of anxiety and anger; despite enjoying my culture, such experiences made me question my authenticity to my culture. Consequently, I felt the need to consistently prove that I was Indian enough.

In hindsight though, I didn’t need to prove anything, especially because the very people I was verifying my authenticity to held similar degrees of knowledge of Indian cultural heritage as myself. But they would remain sneering due to their arrogance. Instead of trying to prove myself to such people, I learned to ignore them just as they ignored me. Instead of moving in circles filled with insecurity, only I can decide how authentic I feel to my culture.

And yes, while sometimes my r’s don’t roll right and I forget how to say something in Hindi, this cannot erase my “Indian-ness”; in fact, nothing really can unless I decide to push that aspect of myself away. And so:

“Yes, I am American. I’m Indian American.”

Anaisha’s Anecdote: The Identity Crisis

My feelings about my cultural identity are … complicated to say the least. I’m Indian American, specifically Bengali American, but the label holds an overwhelming weight, feeling as if I have to maintain an impossible balance between two clashing identities.

Growing up in the Bay Area with its significant Indian American population, I have the privilege of not being an outsider because of my Indian heritage. I never felt weird eating Indian food during lunch because I knew there would be at least one other kid eating food from a similar cuisine. I have a small but close group of Bengali American friends.

Despite this, I’ve always felt somewhat alienated from my Indian heritage. Sure, I love traditional Bengali food, watch Bollywood movies and practice Bharatantyam, an Indian classical dance. Yet, the core of who I am always felt American. Even though I’ve always attended schools with a significant Indian American population, I’m aware that I’ll never be a 50-50 balance between the Indian and American aspects of myself.

I worry that I might be growing distant from my culture, as it becomes harder for me to speak in Bengali and have proper conversations with my grandparents. I worry that I may lose complete touch of my mother tongue, that I’ll never be able to cook Bengali food myself, that I’ll stop watching Bollywood movies every Friday night.

DVHS English teacher Ms. Kim gives some words of advice for students who feel uncertain about the mix of cultural identities that comprise them.

“If you’re struggling with this identity crisis, finding a community is really important,” she explains. “But if you can’t find that community, you can also resort to literature and memoirs … Finding a community of authors and writers who talk about these topics can be a good way to understand the various feelings you may have about this.”

Books I’ve read in Ms. Kim’s English class, such as “Born a Crime” or “The Best We Could Do,” open doors for conversations about the complex web of culture we’re faced with. Although one’s cultural identity is unique, the experience of being an “in-between” of multiple groups is universal for so many people, regardless of their background or where they were born and raised. In the end, it’s only through our communities and conversations that we can realize the common ground that we all hold, and try to confront our anxieties about our conflicting cultures.

Mayukhi’s Anecdote: Just One isn’t Enough

FLEP (short for Foreign Language Enrichment Program): a special program in my elementary school dedicated to exposing kids to different cultures and languages. I was in this program for about five years, from kindergarten to fourth grade, until it got canceled when I entered fifth grade. The class was no different than your usual elementary school classroom, with days of learning English and math and other common subjects, except for the fact that we learned Mandarin as well. Along with learning this beautiful language, I also learned about the different cultures and customs of many East Asian countries. From a very young age, I was exposed to a variety of cultures. However, I sometimes still have trouble finding my own.

As the daughter of first-generation Indian immigrants, I grew up in a very traditional household. I started doing the Indian Classical dance Bharatanatyam at the age of four and since then, it became a very prominent part of my identity. I watched Telugu movies along with family and friends and grew up eating classic South Asian cuisine, like dosa and lemon rice. I indulged in my Hindu religion and eagerly learned about its mythology, yet sometimes I felt far from “Indian.” I felt far from my culture when I visited India and could only speak in broken Telugu. I felt far from my culture when I started preferring American pop music and when I wore shorts in India, with people around me giving me weird looks. I feel more “American” during these times.

But even, the American part of me is not complete. While my friends would bring peanut butter sandwiches for lunch, I would bring my grandma’s handmade chapati and sweets. As a little girl growing up, I never felt like I was purely Indian or American; I always swam through both, picking and choosing parts I related to the most. I learned about different cultures, but never knew which one was mine. As I spent five years in my FLEP class being one of the only people who wasn’t East Asian, I learned that you didn’t have to just be one culture.

I’m not East Asian, but that didn’t stop me from enjoying learning about the culture and hanging out with East Asian friends. This experience helped me understand my own culture more. I realized that I’m not fully Indian or fully American and it’s okay. I’m a mix between the two cultures and even though I might feel like an outsider in either one of them, I shouldn’t change myself in order to fit into either one.

I’m sure many other immigrant children can relate, but it’s important we know that even though we might not fit exactly into a single culture, we shouldn’t change ourselves or pressure ourselves to conform to a single one.

The Ending Note

Cultures, like many aspects of society, serve as identifiers: influencing our clothes, foods, languages, faiths and many other aspects of our lives. However, they can serve as barriers as much as they can help foster character. To be consistently one “thing,” especially in a place like the Bay Area, the melting pot of culture, is unbearably restricting.

As second-generation Americans, there is often pressure to conform with your specific cultures. While assimilating to the American identity, there is also a need to meet the traditional standards of your other cultures on the home front, whether it be through being fluent in a language other than English, knowing a religious prayer or wearing traditional clothes. It becomes a game of “see-saw” to balance two or more identities while also learning to establish your own individual identity.

But, this isn’t a game of see-saw. We are much more than one or two things. We are a beautiful blend of many different cultures, experiences and perspectives. And while there is no single way to overcome the feeling of being an outsider, we hope you remember that there is also not a single way to be “something.” The numerous expectations of what it means to be “anything” leave flaws in everyone’s attempt to belong. You are not alone in this journey and though it may seem a steep climb up, you should not need to change yourself to belong to a home that was always yours.