Recognizing the Asian American Identity for what it is: a myth

Jason Leung via Unsplash

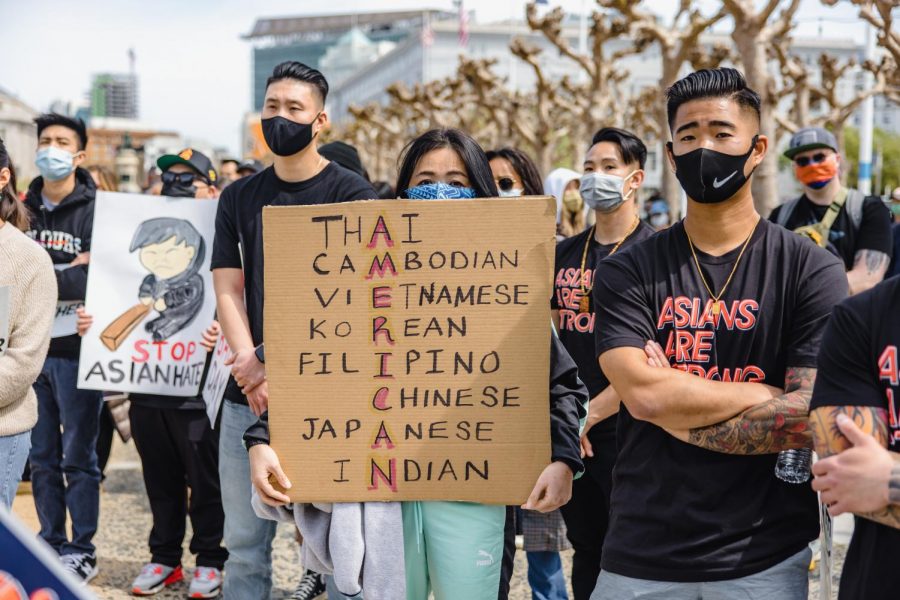

While unity amongst any Asians seems appealing at first, it only masks the stark differences between us instead of wiping them clean.

May 15, 2021

When we think about what defines Asian Americans, usually a couple of key traits will stand out: hard-working, well educated, on a path to Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) or professional degrees and especially in more recent times, the victims of targeted hate crimes and the model minority myth.

What people will not tell you is that all of these assumptions are based on or are outright lies themselves.

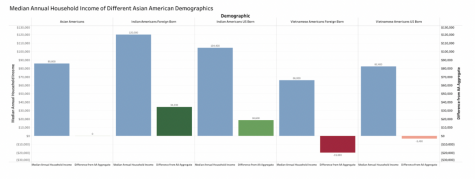

From an initial glance, that claim seems ridiculous if not clearly wrong. Locally, we seem to be built on a manifestation of Asian American success. In a town where 45 percent of the population is Asian American, the median household income of San Ramon families is close to triple that of the American median. Our poverty rate sits at four percent, 260 percent lower than the national average.

Across the nation, the success seems to only multiply: 24 percent of Asian Americans have post-graduate degrees, 84 percent higher than the American average; 54 percent have access to quality schools, the highest among minorities; most staggering of all, the median annual household income of Asian American households is $17 thousand greater than the national average, sitting at nearly $86 thousand.

These statistics are nothing to sneeze at, but it is important to remember that they don’t tell the full story.

In reality, the percent of Asian Americans in the U.S. with at least a high school diploma is actually slightly less than the nationwide average, more Asian Americans graduate with degrees in the humanities than in some STEM fields and Asian Americans hold a slightly higher poverty rate than non-Hispanic white Americans. All of these turn the conventional narrative of Asians in America on its head.

So what’s the deal? Assumptions come from somewhere, so why does the data seem so conflicted?

The answer lies in the fact that Asian Americans are a race, not a monolith. Yes, it is true that 60 percent of Asian Americans come from less than a handful of nations and that their immigrant populations at least in recent years have found great success and socioeconomic gains, tending to shape our ideas about Asian Americans. It is also true however that our definitions cannot simply be accurate for 60 percent of its representatives to be representative of each and every Asian American individual. We cannot blindly accept that entire groups’ historical experiences are discounted from the narrative of the Asian American.

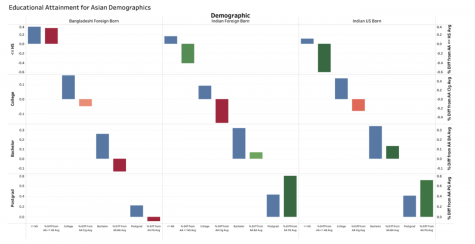

For example, while newer waves of Asian immigration into the U.S. are founded on high economic status from the get go, only a generation ago was the trend entirely different. Vietnamese Americans, the fourth largest demographic of Asians in the U.S., have historically immigrated to the U.S. seeking political asylum and escape from the war-torn and frequently dictatorial conditions of Vietnam. This led to many Vietnamese immigrants coming to America without strong economic safety nets or being highly educated. Thus, Vietnamese Americans historically have been marred by poverty and low educational attainment.

What’s worse is that these contradictions aren’t limited to smaller minorities of Asian populations, they are baked into the disparities of some of the most prevalent ethnic Asians demographics today as well.

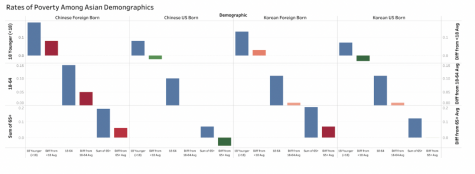

Take Chinese Americans for instance. While we traditionally think of them as the cookie cutter example of the high-achieving “Asian American,” the data is less reflective of that assumption. In fact, Chinese Americans have a higher rate of poverty at nearly every age, and have a slightly higher percentage of people over 25 with a high school degree or less than the Asian standard here in America.

This is skewed surprisingly by the foreign born population, with foreign born Chinese Americans having an average poverty rate 162 percent higher than the American average. This can arguably be attributed to many Chinese Americans historically coming from southern China, a much poorer region than the rest of China, as can be seen by the vast majority of older Chinese American populations speaking Cantonese (a dialect from southern China) as opposed to Mandarin, a dialect spoken more in northern China.

In contrast are U.S. born Chinese Americans, with 43 percent of their population attaining a bachelor’s degree and 29 percent holding a postgraduate degree, and poverty rates below even the Asian American average.

A less surprising contradiction to the Asian American narrative can be seen with modern Korean American history, which can be divided into two parts: pre-economic boom and post. Although today we think of South Korea as an economic powerhouse and politically sound nation (granted even this can be debated), the Korean peninsula just 60 years ago was a hotbed for poverty and bombshells, as the Korean War, Japanese Occupation and political coups and instability decimated their country.

While later economic reconstruction and growth certainly shifted our view of South Korea, this leaves a great divide between older generations and newer generations socio-economic status here in America.

Older immigrant Koreans, who came here seeking political asylum and as refugees from the crises at home, have a 58 percent higher rate of poverty than Asian Americans, still today affecting foreign born Korean populations with a 21 percent lower median household income compared to Asian Americans. New immigrant populations on the other hand benefit greatly from the economic boom of 1970-95 in South Korea.

The annual income of Korean Americans increased by $8 thousand over a four year period from 2010-14 likely due to these newer Korean immigrants, who in the early 2000s were one of the largest benefactors of H-1B visas, or skilled worker visas that provide significant salaries and thus increases to income.

This over-inclusivity of the brutally successful Asian American narrative is not just unrepresentative, but has tangible effects too, being largely responsible for one of the most harmful stereotypes about Asians: The Model Minority Myth.

The Model Minority Myth is generally twofold. Outwardly, it takes the form of assumptions made by a White majority that because Asian Americans can and do attain high levels of success in America, any minority can and should, and so other minorities ought to stop complaining because of Asian Americans achievements.

However, by defining Asian American by only singular instances of success, we not only ignore the varied experiences of many Asians, we support the notion that we are the only minority that can achieve prosperity in America; that because we are the only ones consistently capable of climbing the American social ladder, other minorities are somehow just complainers and not working hard enough. In this we fail to recognize the complex, varied historical experiences of different Asian American subgroups.

Inwardly, the myth pressures relatively less successful Asians to keep quiet about their experiences, that they are failures rather than often products of a complex web of socio-economic and historical conditions. Spoiler: these people tend to be of the less acknowledged ethnicities under the Asian American umbrella.

This oversimplification of the Asian American experience leads to many more hardship stricken Asian ethnicities believing that they should keep quiet about their situations. Instead of bucking the idea of “Asian success,” they should ignore the historical differences between the most successful Asians and the least, and submit to the idea they have failed to live up to supposedly reasonable expectations.

In essence, both facets of the Model Minority Myth can be attributed to the use of “Asian Americans.”

Now of course I am not suggesting that we should abandon all forms of ethnic naming and categorization because of exceptions to the standard. I would go as far to say that they continue to be useful in explicit circumstances. What I am saying is that the broad claims attributed to Asian Americans only perpetuates stereotypes and generalizes experiences that are simply not true for many of its subgroups.

These newly constructed terms like AAPI (Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders), BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of color), and even Hispanic, which are in theory meant to unite groups in solidarity, ironically reveal and often deepen the vast differences in subgroups’ experiences. Moreover, the generalizations we are forced to make actually worsens our conditions and by definition form stereotypes, taking the specific successes of certain sub minorities and assuming they are the baseline for the entire group.

These terms are simply too general and too broad to have practical or beneficial application for most people, if not being outright harmful for others. Until the day comes that all or even a significant number of Asian American experiences become homogeneous, it is just not fit for use. We must come to realize this and stop using terms like Asian American.

Sometimes, recognizing our similarities absolutely has the power to bring us together, and in these cases, we should build up these terms and shared experiences to be celebrated. Other times though, it has the power to reduce us to simple stereotypes, and so we should throw away these categorizations instead. We must remember social constructs are just that: things that we construct and can just as easily tear down.

It is our obligation and our right to pick and choose what social labels we accept and which ones we don’t, because without the ability or the willingness to choose, we leave our devils on the doorstep.