Staying in and coming out: questioning and queerness during quarantine

Isolated and swamped with time to think, many teens began questioning their identities over quarantine.

November 21, 2021

*Names have been changed to preserve privacy.

On the first day of Pride Month 2020, Isabella* came out to her mother. It was 4 a.m.; outside, it was dark and a pandemic was raging.

The two sat on the couch, watching the Netflix sitcom “One Day At a Time.” As character Elena Alvarez came out to her mother on screen, Isabella turned to her own mother. Months of rumination and apprehension culminated in a few words as she revealed to her mother that she was queer. (Queer is an umbrella term for those who don’t identify as heterosexual or cisgender.)

“After I said it, I felt so much better,” she said. “And I was like, ‘Okay, if saying that made me feel that good, then I know I’m not messing with myself. I know it’s real.’”

In a year filled with trauma – both global and personal – quarantine offered a quiet moment for Isabella to self-reflect. Having dealt with a suicide, a fractured family and mental health issues in the past year, quarantine was “a time where I was actually left to myself, [to] marinate in my thoughts.”

Isabella had suspected her sexuality for years, but denied it in an effort to “be straight.” After briefly dating a boy, she realized that she was more “attached to the idea of having a boyfriend than him.” Meanwhile, she was falling for a friend who was a girl.

“But I didn’t really talk about it a lot, I just kind of kept it there and avoided my sexuality as a whole,” she said. “And then nothing much happened.”

It might have stayed that way if it wasn’t for the pandemic.

“I honestly don’t think I would have come out if I didn’t have quarantine,” she said. “All of that was inside of me and I just never told anyone.”

Over quarantine, she discovered the song “Girls Like Girls” by Hayley Kiyoko, a singer widely regarded as “lesbian Jesus.” She also downloaded TikTok in an effort to stay connected with the world and ended up on gay TikTok “in no time.”

“I found myself relating to everything, and I was so confused,” she said. “A part of me was like, ‘Oh this is cool, I like this side of TikTok.’ But then some TikToks are like, ‘If you’re here, you’re gay.’ And I was like, wait.”

“They’re all intended in good nature. It wasn’t the nature of the TikToks, it was the fact that I wasn’t ready to accept myself. And here was my little For You page telling me: you’re a raging homosexual, for lack of a better term.”

Quarantining and questioning

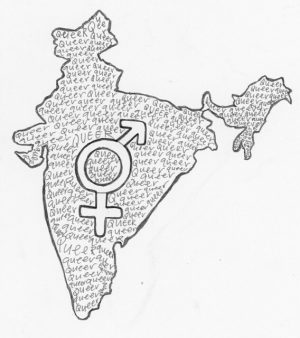

The grinding halt to life as we knew it offered a template for self-reflection. Isolated and swamped with time to think, many teens and adults began questioning their identities. This trend was widely seen, although there have been no surveys as of yet.

“If you’re having an existential crisis, you might as well have a sexuality crisis along with it,” said Clara*, who came out as bisexual during quarantine.

“I think I’ve known for a long time,” she said. “There have been obvious hints, but nothing I really took the time to go and examine and acknowledge until quarantine. I finally had the time to parse through and sort through [it].”

Emily*, a DV senior who realized she was bisexual during quarantine, also acknowledged the impacts that quarantine had on her sexuality.

Because of the social isolation, she began talking online with an old friend. They didn’t have classes together, but it hardly mattered since school had shifted online. It took a while for Emily to realize her feelings for this friend.

“In freshman and sophomore year, [coming out] was pretty frowned upon, but quarantine kind of normalized [it],” she said. “So I felt a lot more comfortable labeling myself.”

Erin*, a senior who uses all pronouns, came out to their friends during quarantine, but is not “officially out.”

“Being able to come out through text rather [than] face-to-face gave me some reassurance,” she said.

“There was a lot of readjusting and jumping back and forth with my identity. The lack of socialization made me adopt and play with other labels, but essentially, I felt the most comfortable with being pansexual,” he said.

Queerness in and out of a pandemic

Rooted in these experiences is an unsettling truth: if it takes a global catastrophe to ease the process of coming out, then there is something fundamentally wrong with our “normal,” un-catastrophized society.

“The funny thing is, I didn’t grow up with a homophobic family … but mostly it just wasn’t talked about or wasn’t normalized,” Isabella said. “I didn’t know the term straight; I just knew gay or ‘normal’ … That’s so toxic, but no one taught me.”

Erin half-jokingly stated that coming out was easier during quarantine “since I didn’t have to face [my friends] after they heard the horror of me being LGBTQ.”

I (the writer) am bisexual, but for the majority of my 17 years, I believed I was straight (with an intense conviction which I now laugh at). In the fall of 2019, I had my first subtle doubts, confirmed by a strange line I recently found scrawled in my notebook: “I always love the wrong people … a girl … and I’m not even gay.”

In my mind, there was no existence of any label outside of straight or gay. I’m a girl. I liked a girl. And I still thought I was straight. Because “gay” wasn’t the right label; and “straight” was, and always has been, the default.

The default is considered “normal”; unfortunately, this often is convoluted into “normal is default.” For Isabella, this was the crux of the issue.

“I was like, what does it mean to be straight? Because I [only] ever heard: you’re gay, you’re different; or you’re ‘normal’ sexuality. I’m like, ‘Oh, no wonder I’m so f*cked up,’” she said.

Exposure – in the form of media and community – provides relief and reassurance for queer students. Isabella found exposure through songs and TikTok, which offered her a community to relate to and adopt.

For students across the country, social media played an impressive role in the process of self-realization and coming out.

“The stakes of exploring my queer identity felt as low as they ever could. Passive curiosity gave into eager scrolling. Some videos were explicitly gay, clips of couples or comedy bits about coming out,” wrote college student Elizabeth Hopkinson.

I sometimes wish I was earlier exposed to even the term “bisexual.” In the rest of my (melodramatic) notebook entry, I continued: “What does this mean? I want to be deciphered. I want to be interpreted and translated into something I recognize.”

Did I even know of the existence of bisexuals back then? I’m not sure. Which is, in itself, very telling. Tucked into a binary construction of the world, my self-coming-out was put off by an entire year peppered with confusion.

Exposure doesn’t perpetuate confusion, nor does it push youth down a slippery slope into the well of gayness. Rather, exposure rids of confusion and demystifies a still stigmatized part of identity. It’s relieving – and arguably necessary – to see someone like oneself, someone who has it all figured out, whether that be related to sexuality or not.

Quarantine offered time for self-reflection, it’s true, but inherent in the isolation was online exposure. TikTok usage rose 180% among 15-25 year olds during quarantine – and helped many embrace their queerness.

“Now it’s just a part of me and I’ve realized that it goes along with all my other identities,” said Isabella. “It’s just there. It doesn’t define me.”

The crippling truth is that some found acceptance, and others hatred and discrimination. As a friend once told me, “The first moment of any queer person’s existence [coming out] is literally created by homophobia.”

“I don’t have anyone telling me it’s okay to be gay,” said Erin, “[But] I believe it enough for myself to be fine with it.”