Contra Costa County express their disapproval towards the Tassajara Parks Project

Contra Costa County Department Of Conservation & Development

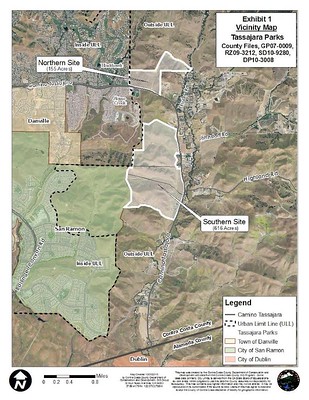

The Board of Supervisors voted to build houses on the map shown.

September 28, 2021

On July 6, 2021, the Contra Costa County Planning Commision voted 4-2 to reject 125 single-family homes from being built on the Tassajara Valley due to water issues, only to be overturned by the Board of Supervisors with four out of five supervisors allowing it. Residents of Contra Costa County, mainly those in San Ramon and Danville, and the Contra Costa Planning Commission expressed their disappointment towards the county, especially the Board of Supervisors, for overruling the vote, allowing the project. This caused the county to be sued by the Town of Danville, the East Bay Municipal Utility District, the Sierra Club, the Greenbelt Alliance, the former county supervisor Donna Gerber and former San Ramon city council member Jim Blickenstaff on how the plan was crossing the urban limit line.

The residents of the county started a petition in an attempt to postpone the building of the houses, gathering 5,541 signatures against the project. Sensing the general opinion of the county, the Planning Commission postponed the decision from June 9 to Sept. 9 in order to hear the opinions of those who wanted to express their direct opinion at the public hearing.

The urban limit line prevents builders from building past that line in order to protect the agricultural land. The urban limit line that the Tassajara Parks Project crosses was last renewed in 2016, and is currently extended to 2026. If the cities were to enter into the preservation agreements, which allows urbanization past the urban limit line, then builders would be able to build past it with no problems. However, San Ramon and Danville did not enter into the preservation agreement, which makes it difficult for the builders to negotiate with the county for more land to urbanize.

“It really comes down to the property owner wanting to make some money. They’ve owned the land for well over 20 years, they’ve come up with different proposals over the years, which have been rejected,” Andersen said. “At this point, I think the developer was ready to move forward, they got the four votes needed from the Board of Supervisors and were ready to move on.”

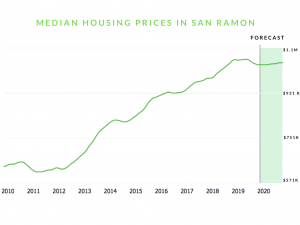

California is indeed in a housing crisis with high prices and not enough homes, and both the county and the state are attempting to solve the crisis by simply building more houses. The residents are fine with building houses, but they are worried about building over the urban limit line as the builders search for open land to develop.

Jia Li, a resident of San Ramon, has constantly posted updates about the Tassajara Parks Project on Nextdoor about how the people of San Ramon and Danville attempted to go against the plan. She expressed her frustration over how the county was not taking the residents’ opinions into consideration even though they clearly expressed their disappointment.

“I know there’s a housing crisis in California, but there’s not a lot of open space left. There’s a reason why there’s an urban limit line, and the fact that the county thinks it’s okay to change the limit without consulting the residents, it’s not right. They decided to go ahead with it, even after tons of residents have opposed it,” Li said. “Do we need any more urbanization or industrial developments on open spaces because we don’t have that much [open space] anymore.”

Supervisor Candace Andersen, one of the supervisors on the Contra Costa County Board of Supervisors, was the only one that opposed the project in the Tassajara Parks Project meeting. She said that they already voted on an urban limit line, however the FT Land LLC, the builders, were negotiating on the preservation agreement.

“The developer drafted a preservation agreement and they started negotiating with Danville, and Danville said, ‘Hey you know what, the only reason you want this preservation agreement is to break the urban limit line.’ And so ultimately, this preservation agreement was really drafted solely to break the urban limit line, and did not really provide new protections, beyond what is already within our agricultural land outside the urban limit line,” said Andersen

Zoe Siegel, the director of climate resilience of the Greenbelt Alliance, emphasized how important these urban limit lines were to climate change. She explained that the urban limit lines makes it harder for builders to develop in those areas because the land is being preserved. She also expressed how building past the urban limit line can increase chances of wildfire, and especially with how homes in California are built with mostly wood and concrete, making it more vulnerable to fire and heat.

“There’s so much value in open space, both for wildfire and greenhouse gas. It’s going to put the surrounding community more at risk of wildfires, [because] nature absorbs heat and so if you add more concrete then it can make the whole community have higher temperature days,” Siegel said.

Li also agrees with Siegel, and mentions how the higher temperatures can contribute to a climate issue that may impact the future. “It’s like we’re at the midst of all of these climate issues, and yet [the builders] thought that it would be okay to go ahead with this,” Li said. “Especially in California, you know, with all the fires and I don’t understand [why they’re doing it].”

Another problem brought up by those dissenting against building past the urban limit line was the lack of water. The East Bay MUD (EBMUD) currently provides water to the limit line, but says that they will not be able to provide enough water to all the new homes, and refuses to provide the water needed in the future area.

Supervisor Andersen disagreed with the rest of the supervisors because the water is a big issue, as is protecting the agricultural land. She also pointed out that even though the EBMUD has clearly stated that they will not be able to provide water to the community, the builders still continued to push their plan.

“The most important reason [why I opposed it] is that there’s no water,” said Andersen. “In order to have a project, you need to have water for it, and because this project is outside the urban limit line, it is outside EBMUD service.”

“When the people that actually regulate the water and distribute the water are saying, ‘We can’t do this’, they should listen to them, and figure out a solution to make sure that we’re building housing where everyone has enough water to drink,” Siegel said. “I think the fact that this developer is moving forward [with] the project, knowing that they don’t have access to water, is very strange.”

However, the builders’ plan has many negative environmental effects coming from the building. Though the hills may seem empty and just have grass, there are still creatures living there in a complete ecosystem, and the hills may be a crucial part to go against climate change.

Li stated, “For sure, there is an ecosystem, and lots of creatures live in them. It’s a home to so many other creatures, and just because it looks bare for people’s eyes doesn’t mean that it doesn’t have anything. This is going to be a huge problem and I think the more industrial or urbanized [areas] we have, the less open spaces we have, then more problems we’re going to have for climate change. It’s just a chain reaction, so I wish that people who have more authority can have a site for a long term solution rather than a short sighted plan of ‘We’re going to build houses and make a lot of money off of it.’”

With many residents signing a petition to pause or stop the urbanization of the Tassajara Valley, the county decided to pause and listen to the public. Within the discussion, the most obvious and important problems were with the lack of water and the future environmental impacts. While the disagreements regarding urbanization may only last now, the environmental effects of this plan may last for a long time.

“Initially the Greenbelt Alliance only cared about protecting the urban limit line and making sure that no development happened outside of that boundary,” Siegel said. “But now there’s so many more important reasons to protect our community.”