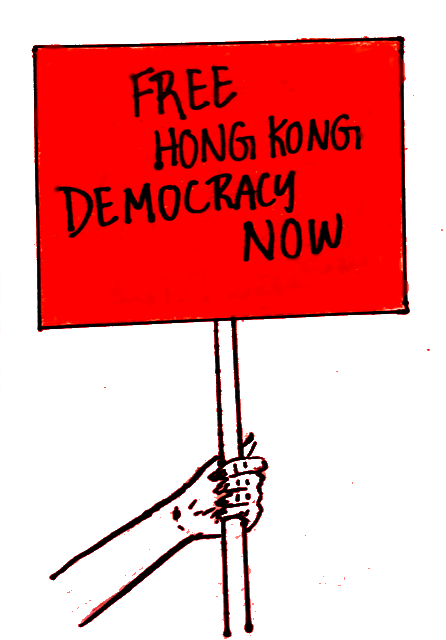

Protests in Hong Kong escalate as demonstrators call for democratic reforms

September 30, 2019

Protests in Hong Kong near the six-month mark as demonstrators escalate their opposition to a controversial extradition bill, demanding democratic reforms and increased autonomy from China.

The protests, which began in March 2019, sparked in opposition to a now-shelved bill proposed by Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam. The Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation (Amendment) Bill would have allowed criminal suspects to be extradited to a wider range of countries, notably including China.

Hong Kong officials argued that the bill would allow suspects to be properly prosecuted, with the Security Bureau citing a Hong Kong resident that could not be tried for murder in Taiwan due to restrictions against extradition. However, the bill was viewed with suspicion by many residents.

I think they’re worried that this extradition bill, which takes away local power, would allow for people that are saying things that are against mainland China to be extradited to China,” Ms. Jeanne Scheppach, AP U.S. History and AP U.S. Government and Politics teacher, said.

Widespread protests broke out in June 2019, with over a million Hong Kongers taking to the streets to march. Violence soon erupted, as protesters attempted to storm Hong Kong’s Legislative Council building while police fired rubber bullets and deployed tear gas.

After mass unrest, Lam suspended the legislation on June 15 and formally withdrew it on Sept. 4. However, the protests have since expanded in scope. The protesters have four main demands that the government has yet to meet: Lam’s resignation, an investigation into police brutality, release of arrested protesters and greater democratic freedoms.

“It was more than just the bill. It was about how Hong Kong was losing its individual freedom as a specialized governed state,” senior Abbie Chong, whose family is from Hong Kong, said. “When they were under the rule of Britain, they had a lot more freedom than when they were returned back to China. Now that it’s declining, that’s why I think there is so much controversy.”

To date, more than 1,100 people have been arrested, and police have used tear gas, bean bag rounds and sponge grenades on protesters. Protesters have rallied behind instances of police brutality, including recently released footage showing two officers at a hospital beating a detained man in his 60s.

“We see police brutality everyday, we have victims everyday,” Bonnie Leung of the pro-democracy Civil Human Rights Front said after the extradition bill was withdrawn. “We cannot just leave it. Hong Kong people will still fight for justice and fight for the future of Hong Kong.”

Protesters are also calling for increased democracy. Hong Kong was controlled by Britain until 1997, when it was passed to China under a “one country, two systems” policy. Hong Kong belongs to China, but under its constitution, the Basic Law, it has the right to develop its own democracy and citizens are guaranteed freedom of speech, press and protest.

However, China has increasingly asserted control over Hong Kong in recent years by reinterpreting the Basic Law, causing frustration among civilians.

“Hong Kong is part of China, and its affairs are entirely China’s internal affairs,” Hua Chunying, a spokesperson for the Chinese Foreign Ministry, said in August.

This has sparked resentment in many residents, who identify with Hong Kong rather than China and wish to maintain their autonomy.

“I think they’re worried about the growing power of China under the leadership of [President] Xi [Jinping],” Scheppach explained. “A lot of my students have been saying that China looks to be going back to a more quasi-totalitarian state than it was before; Xi has a very harsh hand on the Chinese population.”

Furthermore, Hong Kong’s Chief Executive is not elected by popular vote. Instead, candidates are elected by an Election Committee of 1,200 people, composed of prominent individuals and special interest groups.

“It’s been an ongoing fight to have voting rights that are more than just a Chinese representative,” Chong claimed. “I think that’s what they should have and what they’ve been fighting for, past just the extradition bill.”

Recently, protests have expanded to the Hong Kong International Airport, one of the world’s busiest travel hubs. The airport has been closed by protests for days at a time, and nearly 1,000 flights were affected by the protests in August, reflective of a broader impact on the economy. Hotel occupancy has decreased by double digits and protests have also hurt the retail sector. Combined with the U.S.-China trade war, experts predict a decrease in economic growth.

“The recent protests and demonstrations in Hong Kong have turned into radical violent behaviors that seriously violate the law, undermine security and social order in Hong Kong and endanger local people’s safety, property and normal life,” Hua said.

While Lam withdrew the bill, she declined to open an independent investigation into police brutality, instead referring to the Independent Police Complaints Council (IPCC). She also called for a return to order and dialogue between the involved parties.

“Let’s replace conflicts with conversations and look for solutions,” Lam said.

As the demonstrations intensify and tensions escalate between protesters and the government, the unrest in Hong Kong will have far-reaching consequences.

“I know a lot of people living in Hong Kong that are really concerned that if they really do lose all their freedom as specialized governed area, [they’ll want] to move out of Hong Kong,” Chong said.

“I think there’s a bigger concern [about] the growing power of China, and, ‘Are they going to clamp down again? Do we need to keep pressing because another kind of this bill is going to happen later on?’” Sheppach added.