JID breathes life into Atlanta hip hop in his masterpiece “The Forever Story”

Naksa Demini

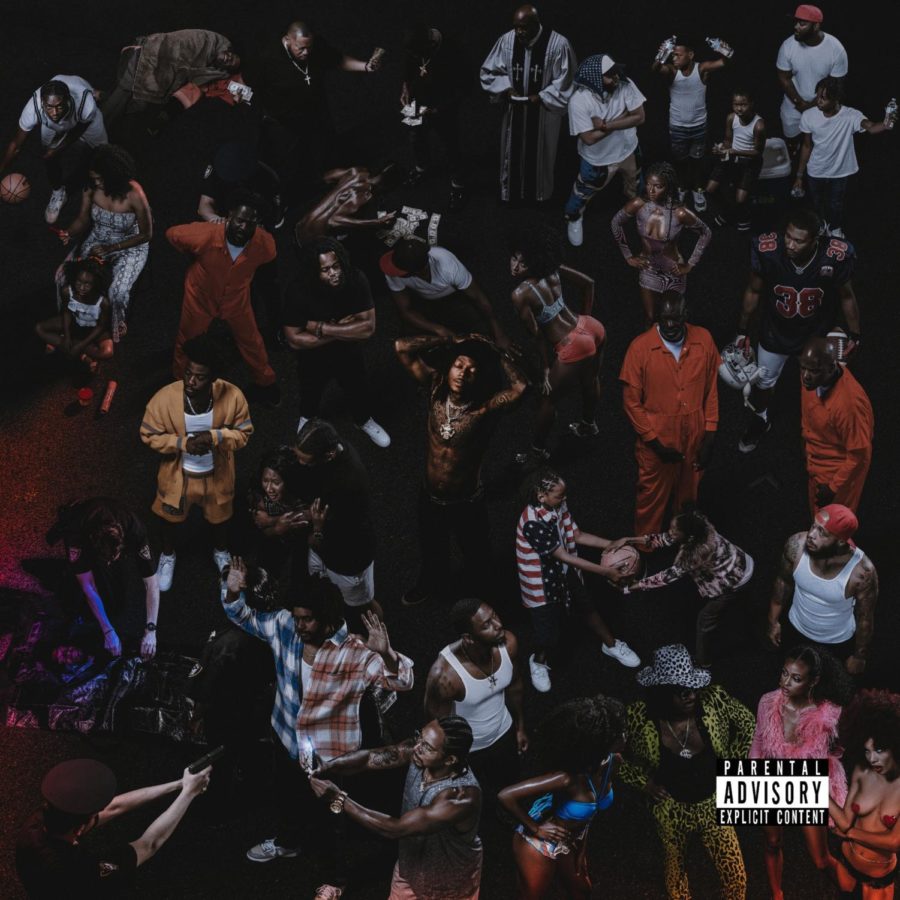

Album cover of JID’s latest album “The Forever Story,” depicting JID at the center of violence, religion, drugs and sex.

October 10, 2022

In the hip hop world, there is a great divide. The “popular” and the “conscious.” It divides artists like Kendrick Lamar and Drake, Migos and Lupe Fiasco, SOBxRE and The Koreatown Oddity. The question comes down to this: do you want your music to bump or do you want your music to bump your heart?

And fairly, some artists can straddle the line. Kendrick Lamar is arguably one of the most popular rappers in the world, and renowned both among pop circles and critically inclined circles. But as a matter of generality, the divide is strict; a white picket fence unfortunately reminiscent and analogous to African American history of redlining, of black nationalism, and of tokenism.

So against all odds, against these very divides within African American culture and within the American racial divide, JID puts himself in the line of succession to artists like Kendrick Lamar, 2Pac, and Common as one of the few who can break through the chasm within hip hop, and within American society.

Released on Aug. 26, 2022, “The Forever Story” comes as JID’s third major release and eighth tape over the last 12 years. The album itself comes as a spiritual successor to his first album, “The Never Story,” released in 2017.

Much of “The Forever Story” as a result takes its thematic ideas and atmosphere from “The Never Story.” The cover of his newest album, for example, even serves as an extension of “The Never Story’s” cover. JID is surrounded by the imagery of sex, convicts, and police which adorned his earlier record, cluing listeners immediately to the thematic nature of his newest LP.

Yet despite these broad similarities and call-backs to previous projects of his, JID’s genius comes through opulently and freshly through his newest record, not because of necessarily a divergence of sound or introduction of new thematic elements, but purely because of the dedication and craft imbued in this album.

Much of this album, for example, brings over JID’s core producers from his previous records “The Never Story” and “Dicaprio 2,” the instrumentation of the record taking heavy cues from these album’s sounds.

But on these previous albums, one common critique was their reliance on JID’s own phrasing and performance for body sonically. On this newest album, JID extends an idea explored partially on songs like “Never,” by making use of repeated beat switches and polarized flips of the same sample on a single track, and milks every drop out of each producer and each track through this production style.

Major singles released from the album like “Surround Sound” flip Aretha Franklin and Mos Def in two wildly different ways, mirrored and bolstered by JID’s variable and eccentric flows on each beat. These polarized flows provide listeners with a sense of disorientation and constant movement, and prevent listeners from ever gaining their footing entirely in the best way possible. His effortless switching between trap bangers and slow, New York-style conscious hip hop reminiscent of Wu-Tang flow switching and water-smooth, cool performances feel at once at odds with each other and yet perfectly balanced.

This same dynamicity found internally on tracks is exhibited between tracks as well, keeping listeners on their toes as they switch seamlessly between smoky, jazz rap one moment to poetic, soulful ballads the next to grimy, southern hip hop the next.

This extensive reach that JID demonstrates does not only come in the form of the album’s nearly flawless production, but specifically in his ability to adapt to any of the beats put in front of him. The record sees him using entirely different flows on every single track and often multiple unique and pointed flows within a single track, and performance wise bringing a bombastic and punchy performance on every track.

What again is so incredible about this album is specifically his ability to do all of this while tying together a cohesive album, the thematic elements of course being the forefront of such analysis, but aspects like this album’s percussion, for instance, providing a rock-solid foundation for the fluid explorations of sound that JID dares to take on within this record. The vast majority of this record makes use of dry, hollow drums and thin claps that give maximalist space to the bass and 808s on this LP, something the mixing makes ready use of with honey-thick, liquidus bass that evokes feelings of sinking directly into the instrumental, falling into a world of JID’s own design.

Tracks like “Can’t Punk Me” with the help of EARTHGANG sound right off Outkasts’ seminal and genre-defining Atlanta record “Aquemini,” as if Andre 3000 was transported directly to 2018 and made a trap remix of “West Savannah,” one of the “Aquemini’s” most famous tracks.

Sure, EARTHGANG’s heavy influence from Outkast is readily apparent to most listeners, but what sells this track is not its homages to the forebears of Southern hip hop like Tommy Wright III or UGK, but its stutter-step quick-witted flows paired with the sultry jazz rap instrumentation. The open hats literally sound like someone smoking a joint, and the cut and screwed piano lends a grimy, underground sensibility to the track, supported by the pitter patter flows of Johnny Venus, the slow high, straightforward baseline of Doctor Dot, and the piercing, punchy hook by JID.

And again, this track exemplifies the incredible balance that defines this record. Throughout the LP, JID at no point sacrifices his lyrical upsides or nuanced, personal explorations of his racial identity and journey through life, whilst still maintaining strong pop bangers and mainstream trap singles. JID seems not to care about matters of synthesis or compromise, but instead provides both mainstream and underground hip hop communities the exact album they wanted from JID at the same time.

See no further than in a recording of a voicemail that starts off the entire album, someone tells JID “Oh, so you don’t call now, you don’t pick up the motherf**kin’ phone, n*gga? Oh, okay. Yeah, yeah. You are who I thought you was, n*gga. You plastic, n*gga, that means you motherf**kin’ fake,” JID playing such a message in an on-the-nose acknowledgement of how others view him and how he seems to exhibit all of the opposite qualities of what others demand him to be.

This sense of wanting to honor and acknowledge his roots and fundamental creed and goodness whilst chasing his own ideas and dreams of success as they evolve against the grain of what society and his community expected him to be pervades the entirety of the album, and JID’s incredibly dense lyrics provide introspective and deeply personal looks at his own life and struggle to find such a balance.

This creation of success in his own image is best shown on the album’s magnum opus, the gospel-like choral ballad “Kody Blue 31.” Here JID writes about the perseverance required as a Black man in American to keep pursuing greatness and success, speaking how “I watch my momma lose her momma, go through drama and trauma but had to keep her head high so we don’t f**kin’ know,” and that “When the world’s feelin’ enormous on your back and on your arms, when your feet just as heavy you been draggin’ through the storm, starin’ at the city, but you trapped inside this hole, so back up off the ropes, keep swangin’ on.”

His descriptions of the hardships he has endured throughout his life as well as the constantly rising, elevating tone of voice he takes on as he switches from gospel rap and conscious hip hop a la Common to eventually soulful and wholehearted singing describes on a higher level the actual climb that he has had to undertake, taking on the burdens of his family and friends and the love of himself and others.

JID writes of how his hardship is born of the racism that surrounded his history and past, writing that “Swastikas and the police, hang a n*gga, swangin’ rope. He be tryna swang on me, but I was with likе fifty folks and he ain’t know. But what was worse, I don’t evеn want no beef with bro,” aptly pointing to the impersonality and ambiguous nature of systemic racism in the country today, the unwanting of black men especially to be part of such hatred.

He repeats that “We was toted, we was soldiers, we was soulless we was sold,” describing the loss of self he has experienced as a black man, and how his fight to be successful is not just to be powerful but to even be seen as himself, this fighting for his own success thus a manifestation of his wanting to be truly seen by others not just for his success but as a black man as well.

This internal conflict between wanting to fight the gang lifestyle and poverty that surrounds him and seems to forcefully define him from the external white society whilst still not bending to white ideas of success and instead molding himself as a powerful black man of his own creation helps listeners understand this constant teetering act JID has played throughout his life. The constant fight JID has to be anti-mainstream and antithetical to the culture white people have defined black people as being fit for whilst still wanting to be true to his black heritage is represented through the constant shifts on the album, the movements between southern hip hop influence and gospel balladry, the flipping of the same samples in two polarized manners.

The fundamental two sides of himself that JID struggles with are at the very core of this album, and speaks to listeners in a way not just unique to its dynamic production, its variable flows and features or its lyrical content, but at the center of JID himself. This album is JID, and he has crafted in such a way that is not only true to himself and successful in the mainstream, but entirely powerful in its perfection as a musical masterpiece.

This intense and central theme is not one often communicated on mainstream or underground albums, and almost none as well done as this. JID isn’t Kendrick, he’ll never have his lyrical content, and he isn’t Migos either, he’ll never have the pop accessibility. But the reality is that JID doesn’t want to be or need to be anyone else, he is himself. JID has crafted an album that is entirely representative of who he is and what he wants to be. An artistic formation of all of the history of his race, his family, his legacy that internalizes the struggle of his being and his rise as himself.

That artistic perfection and pursuit on “The Forever Story,” whether one is mainstream or underground, a fan of pop or hip hop or black or white, can be and should be appreciated and experienced by any musical fan willing and wanting to be amazed.