A Kashmiri Pandit tragedy survivor recounts his gruesome experiences

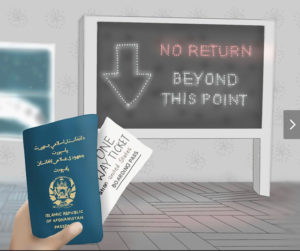

Kashmiri Pandits face a struggle in returning to their homelands due to being continuously oppressed

May 27, 2022

Makhan Lal Bindroo, a pharmacist in Srinagar’s landmark medical store was shot dead this past October by terrorists. His killing was the latest in a long line of persecution against the Kashmiri Pandit community, a group of indigenous Hindus in the valley of Kashmir located at the northern tip of India.

The Pandits’ history in the valley dates back to ancient times. Ravaged by Sikandar Shah Mir, a 15th-century Kashmiri Sultan, the now-ruined Martand Sun Temple is a prime example of the Pandits’ long history in the valley. According to accounts such as the Baharistan-i-Shahi, Sikandar “was infused with a zeal for demolishing idol-houses, destroying the temples and idols of the infidels.” His crusade against the Pandits was one of many throughout history.

In total, the Kashmiri Pandits have gone through seven different generations of ethnic cleansings in the valley, the most recent of which came in 1990. During the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, it is estimated that up to 250,000 Kashmiri Pandits fled the valley under the potential threat of death by terrorists. Terror outfits such as the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) and its leader Yasin Malik are acknowledged to be some of the main perpetrators of the attacks. Chanting slogans such as “ralive, tsalive, ya galive,” (leave, convert, or perish) the JKLF and other groups would soon drive Pandits out of their homeland by the thousands.

Thousands of those who fled ultimately as a result of such threats and violence ended up in places around India and America. Dr. Surinder Kaul, an ER Specialist and Assistant Professor at the Baylor College of Medicine, recounts his experience as a Kashmiri Pandit seeking refuge. When threats of militant activity became serious in the Kashmir valley, Kaul was a student completing his medical internship at Government Medical College Kashmir in Srinagar.

For the 80,000 Pandits who weren’t killed by starvation, homelessness, snake bites or natural causes, many were injured patients that Kaul had to treat. He would soon have to treat both victims and perpetrators of the tragedy against his community.

“I was witnessing all these casualties that were happening, I had received so many dead bodies and I have declared them dead, most of them were people from my own community,” he said.

Starting in 1989, the threats towards Pandits transitioned from being sporadic occurrences of violence to a regular part of life.

“From 1989 onwards, there [were] targeted killings of Kashmiri Hindus and mass rapes of Pandits. The militants also chopped up people’s bodies and kept the remnants to hang in the open to scare the remaining Pandit population,” Kaul said.

In January of 1990, the non-Pandit population rallied behind the militants and started to be forcefully removed from Kashmir.

“From January 18th, the intervening night, all the people, in all the towns, religions, districts and in all the cities, they came out and made very obnoxious slogans against Kashmiri Pandits,” Kaul said.

“The police were muted and the political system collapsed willfully. And all those people who have been against the occupation of the Pandits got the license to do whatever they want,” Kaul said.

Accounts report that Pandit politicians were coerced into submission by terror groups: Intelligence Bureau Officers of Pandit origin, ML Bhan and Tej Kishen Razdan, were shot dead in 1990.

These experiences left Kaul and the Pandit community scarred and traumatized. With terrifying accounts of killings such as that of Girija Tickoo, Tika Lal Taploo and Satish Kumar Tickoo left untold by the media, the story of the ethnic cleansing in Kashmir remains relatively unknown and underrepresented.

“But this story remains hidden from India from all over the globe, because India is a mighty democracy and it was was never allowed to come out,” Kaul said. “So there were a lot of agencies who were saying that this thing should not come as it could stain the mighty dog known as India. We became a sort of a sacrificial board.”

Hence due to large acts of covering up by different governments, the tragedy in Kashmir continues to be unknown to many people- it continues to be left out of textbooks and discounted by society. Even the real nature of what happened in Kashmir is disputed at times. Many of the Kashmiri Pandits refer to these events as a genocide against their community. However, some historians contentiously refer to it as an exodus.

With a look of sadness, Kaul stated, “Almost 100% of this community left their ancestral homes and their vitals documents. Now, after they became victims of ethnic cleansing, it’s a small community.”

Today, only about 3,000 Pandits remain in the Kashmir Valley.

In 2018, Kaul and other Pandits wanted to portray the struggles that Kashmiri Pandits had to go through in the form of a Bollywood movie. Kaul states “It wasn’t until our conversation in 2018 with director Vivek Agnihotri in which he decided that yes, he will make a movie out of this”. While some such as The Print call the massacres, such as the Chittisinghpura massacre, depicted in Kashmir files “disturbing and discomforting,” the events depicted in Kashmir Files are entirely based upon first-hand accounts by survivors of the tragedy in Kashmir.

“We facilitated around 700 testimonials from such firsthand victims all over the globe,” Kaul recalled.

Kashmir Files topped the Bollywood box office, making 252.6 crore rupees; as a result, it made the world aware of real incidents that happened in the Kashmir ethnic cleansing.

For Kaul, the success of his very first movie has presented opportunities for him to make a difference on an international scale. On May 16, 2022, Kaul addressed the United Nations General assembly in New York on international migration and terrorism, specifically about the persecution of the Kashmiri Hindus.

Similarly, Kaul strives to bring awareness to the issue through his own organization. Once the Pandits were separated from their homeland, many Pandits feared losing their identity. However, to combat this, Kaul founded the Global Kashmiri Pandit Diaspora (GKPD), a civil society movement that unites Kashmiri Pandits with the goal of spreading awareness about the ethnic cleansing.

“Already a very small group of people got scattered here and there, so there was a need to bring all these pieces together for a very consolidated response … it was an effort to consolidate the entire community for one voice and to speak up so that this does not happen to any other community in the world,” Kaul said.

Kaul currently resides with his family in Houston, Texas and through his organization, he hopes to spread more and more awareness about the ethnic cleansing in Kashmir, as well as trying to reunite a shattered community.

While initial steps to rebuilding Kashmir are taking place such as the abolition of the discriminating section 370, all the fighting has caused the true beauty of Kashmir to disappear, and the once special remembrance of Kashmir in the hearts of its past inhibitors has been masked by memories of violence and destruction.

“The whole thing was that maybe after 15 to 20 days things will get better and we will go back, but the problem is that day never happened. It has been 32 years and that day has not come,” Kaul said.

Kaul hasn’t gone back to Kashmir since.