Aesthetic activism is threatening to harm meaningful social justice

Photo by Heather Mount via Umsplash

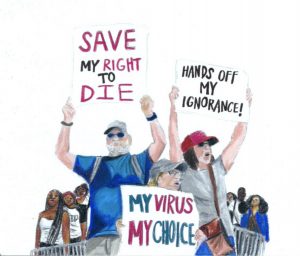

A women protesting in the March For Our Lives protest holds up a sign that reads ” Does anything even matter anymore?”. The March For Our Lives in 2018 was a nationwide protest against gun violence at schools. Despite its immediate national presence, it nearly immediately faded from popular conscience and its effects have remained largely imagined, there being no more major protests or significant gun regulation laws passed since.

November 26, 2021

There is a plague spreading across the U.S. Yes, as ominous and as hilariously ridiculous as that sounds, it’s unfortunately true. The plague we speak of isn’t physical however, at least not at first. It’s not any kind of virus you might expect. The disease is online activism.

Online activism is an imminent threat to healthy political discourse in its current shape and form. It promotes reductionism, only intensifying the commodification of political topics and overwhelms consumers with a wealth of topics and information that hardly contribute to tangible or meaningful political change.

The prevalence of online activism is widespread on the internet, most predominantly bolstered by its most enigmatic figures, oftentimes in the form of reposting fundraisers or spreading awareness through infographics. Although all of these in their purest form are not necessarily harmful and can even be potentially positive, more often than not they are superfluous and meaningless affairs.

Fundraisers online cease to promote well-founded and tangible causes, and instead donate money to wide-reaching and ambiguous causes that no longer benefit as much or at all from mass donations in the way that donations to reputable and long-standing organizations might. Instead of spreading awareness for wide-spread but underrepresented issues that have pertinence to many and thus clear impacts, awareness online becomes more an opportunity to shed light on incredibly niche and in effect often unimportant issues.

Yet despite these potential downsides, online activism has only seen growth over the last handful of years. This is largely in part due to the rise of influencers and more specifically popular social media accounts that act as quasi-influencers in their following, online presence and influence. With the nature of online culture, influencers online today can even be largely anonymous, and can gain notoriety for anything, including simple political activism and positive social justice.

These accounts and personalities have taken hold of the conversations on the internet almost entirely, coming to include political discussion over the last decade or so. As these accounts have increasingly fed a stream of political discourse onto user’s feeds and timelines, it becomes clear that politics in large part has come to dominate our time on social media.

Its prevalence seems at first to be only beneficial; why would it be a problem if these influencers are using their platforms to make others aware of causes they may not otherwise be aware of?

But its mask of positivity hides its deceit. The reality is that these efforts most often go towards completely misinformed or oversimplified forms of activism and politics that benefit no one.

Take one of the most popular instagram activist accounts: “shityoushouldcareabout”. Nearly every day they commit themselves to re-posting infographics about hot topic issues such as abortion rights, climate change and how “Gucci drip [is] feeding us candid Harry [Styles] shots … as they should.”

“shityoushouldcareabout” embodies exactly how nearly all of online activism is more culture than substance. Each post seems to be geared most heavily towards aesthetic over actual substantive impact. Among their topics of interest, they often divulge into overstated points about topics already understood, indulgences in nearly irrelevant and unimportant issues and literal misinformation.

Almost all of their posts manage to redirect any current event inevitably into a critique of capitalism, or irrelevant topics like “predatory” Multi-level Marketing schemes on Tiktok. If they’re not doing that, they’re spewing blatant misinformation and misrepresentations of reality, like when they propagated the myth that Chick-fil-A, a major fast food chain in the U.S., reneged on promises not to donate to anti-LGBTQIA+ funds and instead directly promoted anti-transgender legislation and anti-transgender organizations.

The reality, however, was that Chick-fil-A had made no such explicit promises, and in fact had donated to organizations that themselves donated to both protecting and removing LGBTQIA+ laws, and donated to both sides of the aisle politically, which in no way indicates that they are somehow clearly biased against the LGBTQIA+ community.

The perspective online was much different though, largely because of “shityoushouldcareabout” and accounts like it, who all made their own posts about the topic and provided vehement rhetoric to boycott Chick-fil-A. Even if all the attention generated online may have made people more aware of the state of LGBTQIA+ rights, there was hardly any direction towards a meaningful piece of potential positive change.

This common occurrence of blind hatred towards a company or figure is rapidly becoming the norm online, with major activist accounts like “Impact” posting in early March about how within only 100 days of President Biden’s term, he had somehow “disappointed us already.”

These critiques, while potentially truthful or well-founded, more often than not are quick-witted takes given not out of fairness but out of political theatre. The idea, for example, that it’s possible to judge the merit of a US presidency within the first 100 days of a 1461 days of a presidential term is difficult to argue, likely instead propagated because of its flashiness.

On top of that, a number of these things were proven wrong within only a couple of months, with the criticism of President Biden’s administration’s failure to provide stimulus checks proven wrong after Biden’s administration began distributing stimulus checks on March 12, only nine days after the infographic was posted.

And this is only the very surface level of online activism. Numerous accounts with tens of thousands to even millions of followers post every day to provide their followers with a flood of information. All of them, mind you, aimed at invigorating and playing on the emotions of the layperson to demand more and more awareness and activism to engross one deeper in the web of social activism. This only seems to distract from the actual change that needs to happen in this world as more people become enveloped in the web of online activism and remove themselves from any possibility of meaningful or relevant change.

Yet there seems to be only excuses for online activism. Yes, some may say, while it does promote oversimplified and often misguided efforts, they are still positive. And yes, while fake support fails to address the root causes of many of these problems or to the greater causes they are a part of, they bring necessary awareness that can lead others to those root causes or issues.

But to say that this is all we should expect of influencers is absolutely a farce. The notion that we should expect this milquetoast form of activism of people with the level of notoriety influencers hold is ridiculous, and not at all the standard we hold anyone else to.

We expect politicians of similar popular conscience to be held accountable, other mainstream media figures as well, so why don’t we ask the same of our online activists? If these people have the influence they have over others, they ought to take that responsibility seriously, and properly platform causes that are not only positive but also proportionally positive and meaningful for the level of influence they have.

And let’s be clear: they absolutely have influence. The $5.1 billion in fundraising people on the internet have collectively supported speaks volumes to how overwhelming and potentially effective support can be if people are aware and dedicated enough.

“I want to say that’s why social media can be very positive, because we’re getting so much more information out there. However, it’s just really important that you’re careful with what you read,” Ms. Hanna Love, DVHS English 12 Social Justice teacher, said.

This issue of online support mired with meaninglessness or misinformation bears itself out most clearly with fundraising, with many fundraising efforts dedicated to hopeless and completely irrelevant causes that cannot simply be solved with enough dollars spent: the exact opposite kinds of efforts these funds need to go towards.

For example, a recent effort to “save the elephants” has overtaken Instagram, where the account “patcopets” asks that for the small price of a repost and a follow, they will donate one cent to “save the elephants.” Their graphics, which include imagery of an elephant on fire, are intended to spark an emotional response in viewers so they will participate in the fundraiser. However, rarely will you hear people acknowledging that “patcopets” rarely actually provides proof of their fundraising, and that the provision of funds does not in and of itself save any elephants to speak of. “Patcopets” continually makes post after post about a variety of topics, despite repeated provings that fundraisers like it have no actual impact on the issues they speak about.

If not a fundraising effort, these online activists’ posts tend to be eye-catching immediate takes that will get a viewer to repost and engage with the media without an expectation to look further into its truthfulness.

In fact, many influencers only propagate activist causes the way they do purely for popularity. It is, ironically despite all their talk of capitalism and the evils of the elite, a form of the rich getting richer. These influencers seek to please the masses, or the consumer in the rote view of capitalism, where their product of online activism and supposed political awareness are provided handedly in exchange for social capital in the form of likes.

This social capital is not merely intangible monopoly money. Joe Gagliese, a co-founder of an influencer agency that promotes and funds influencers, stated during an interview with Vox in 2018 that “someone that has 10,000-50,000 followers is actually pretty valuable. They used to only pick up a couple hundred bucks, but today, they get a minimum of a few thousands dollars a post.”

These people get paid based on their following and engagement, and so necessarily, content that drives their metrics up and glues eyes to their screens increases the amount of dollars these people get paid. To them, regardless if it’s important or relevant or potentially impactful to them or not, the attention generated is worth vastly more, monetarily or socially.

The idea of generating an income from helping make an impact is quite attractive. For many, the feeling of having made an impact is vastly more important than actually making one. The feeling of belonging to something positive and meaningful creates a culture of truth and omniscience above those who are not part of it. The tribalism we engage with because of our addiction to feeling of being in the right to others thus manifests itself through online activism as well.

“Our immediate instinct is to confirm our own bias. It is our instinct immediately to be like, ‘Ha! See, I told you, that’s why this thing is right.’ Because we love being right as human nature,” Love said, in reference to why people engage with content online.

And the continued lack of change or effect on these causes actually only promotes hate and increases the number of eyes glued to influencers’ posts. We demand to know more and why one’s justice hasn’t been found, feeding the flames of negativity that allows influencers to reap their sacred social credit in the currency of reposts and follows and likes from us in exchange for our dosage of negative energy off of misguided efforts—our high of demagoguing.

This negativity has manifested itself in real-world consequences. As recently as February 2021, a supposed news organization based in India known as The Tatva, founded a year earlier in February 2020, reported on a Hindu youth who had been murdered. The reports, however, corrobrated without solid grounds that he had been “lynched to death by a Muslim mob in Delhi for saying ‘Jai Shri Ram’ and collecting money for Ram Mandir,” demonstrating an immense warping of the truthful murder of a man simply for the disparagement of Muslims.

This then spread to The Tatva’s now banned Instagram account, which only furthered the Islamaphobic sentiments by continuing to claim without hard, legal evidence that the Hindu youth was murdered specifically by Muslims for practicing his religion, and by adding in their caption that the “incident will be left unnoticed because his name wasnt [sic] Tabrez, [and] he didn’t belong to a minority population,” in reference to the Tabrez Ansari lynching, where a Muslim man was forcibly tied to a tree and beaten to death by a mob of Hindus, and forced to chant Hindu religious slogans.

The post by The Tatva immediately garnered immense virality on Instagram, and in turn promoted their Hindu nationalist pseudo-propaganda that Muslims were in fact murderous and treacherous, and the racist sentiment that people somehow only care about murder and lynching if occurring to Muslims, not to the Hindu majority.

These clear Islamophobic statements have nearly one-to-one parallels with white nationalist rhetoric here in America, literally stating that “if you don’t condemn this mob lynching just because the victim belongs to a majority religion, then YOU ARE THE PROBLEM,” insinuating that despite the comparatively minute quantity of Hindu and white murders by Muslims, Muslims ought to be condemdned more often and more harshly than a majority population for killings.

Yet all of this went unnoticed to the nearly quarter of a million people who liked The Tatva’s post. In part, this is because it is rare that anyone outside of the Indian subcontinent knows of the long and increasingly prevalent Islamophobia among the Hindu majority of India especially, and of the deep-rooted conflicts between Bangladesh, India and Pakistan.

But it is also because we are unwilling to see what is right in front of us. Again, the condemnation of a minority using a single story in an attempt to distract from bigotry amongst a majority population is the exact tactics that hateful and bigoted groups like white nationalists have used for centuries now.

“It is scary that we’ll have people say, ‘I just saw this one thing, therefore everything must be true about this specific [thing].’ And all of a sudden, they’ve got all these [upvotes]… likes, [their posts] get to the top of Reddit pages, [their posts] get to the top of socials, [their posts] get to the top of TikTok,” Love said.

It is as the founder of The Tatva notes, “[The Tatva has] become a voice for the youth that influence [India]… from Current affairs to pop-culture and politics in which genZ [sic] is actively taking part … to create a platform to cater their generation’s ideas.”

The Tatva, like most other influential media presences today, did not necessarily start out as radical or pandering, but became so out of a greater catering towards us, the consumer. What media bodies like The Tatva have learned is that we easily become consumed by our own desire for groupthink, and have thus used our fixation for nothing short of blind, hateful propaganda meant to proselytize and radicalize viewers.

Despite what some may espouse, this type of negative and disparaging energy is not the best approach towards political activism. Yes, thorough discourse in any democratic society is absolutely necessary for it to function, but the notion that blind hatred and despondence towards others somehow improves our understanding of, engagement with or positive action towards social justice is ridiculous. All blind hatred can do is fuel our own desire to bitterly wage war against other groups of humans: not in an effort to mutually improve, but instead to profit off of our own destruction.

Therein lies the reason why these accounts are still posted: because we support them. If this subpar form of activism and meaningless culture of politics were actually so pertinent to us, we simply wouldn’t support these accounts. We would realize that the way we engage with politics currently isn’t actually benefiting the people it needs to, and instead serves only as a delicacy for the well-off and privileged who don’t have to think about these things critically because these political causes don’t actually affect them. This disease of online activism isn’t rampant because of our lack of awareness, but because of our ignorance.

Online activism is a disease that isn’t going away any time soon. Not just because influencers have taken hold of them as their main commodity, but because we have placated ourselves to their harm. The influencer’s spread of toxic online activism isn’t just a problem in and of itself: it is reflective of a greater diminished regard for truthful informative content by all people in the world today. We have become numb due to our lack of regard for meaningful political change; for the masses, the culture of politics has subsumed its substance.

When asked about the actual solution to misinformation and malicious influencers, Love noted the importance of our own consciousness and active combatance against such threats.

“It’s to make sure … that my students know that you are constantly going to be fed a lot of information … I want them to form their own opinions based on what they believe based on their own values. As long as they’re taking all of it in and as long as they’re filtering … to form opinions based on actual reading, I think [that’s] what’s really important,” Love said.

Is online activism a disease? Absolutely. Are its main spreaders influencers? Technically. But the cure we should advocate for should not be of or for them, but for once be of and for ourselves.