Dougherty’s over-competitive perspective on college admissions causes unnecessary stress among students

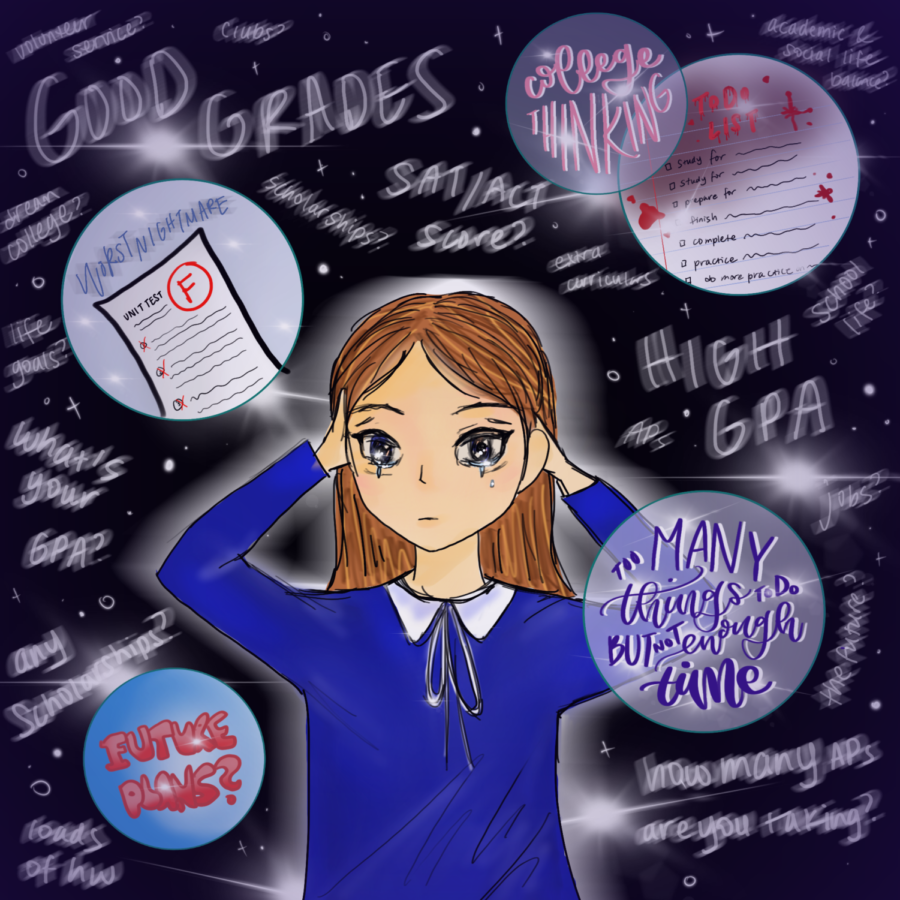

High school students too often take on more than they can handle, thinking it’s necessary to get into their dream school.

November 2, 2021

From filling their schedules with AP and Honors classes to joining every extracurricular they can find, Dougherty students are known for overburdening themselves for the sake of getting into a selective college. What many students fail to realize is that piling all these responsibilities onto themselves isn’t necessarily going to help them get into an elite college, and even if it does, such colleges are not inherently the best option just because of their big name.

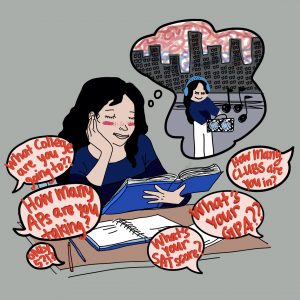

Carrie Fox, an academic counselor at Dougherty Valley, explained, “There are people always asking about the magic number of APs. They think you need to take all AP classes to get into college, which is not true, obviously.”

Devyn Gonsalves, an English 9 and 10 teacher who graduated from DVHS in 2016, exemplifies this with a story from her time at Dougherty Valley when she was told that she was wasting her potential and that she wouldn’t get into a good college because she was only taking AP Literature while many of her peers were taking more weighted classes.

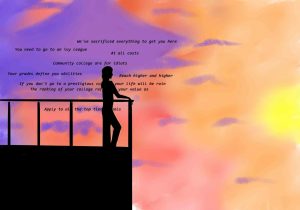

However, this mindset of trying to be the “perfect student” in hopes of getting accepted into a top-tier college is misleading since the whole admissions process can be quite random.

Fox corroborated, “We don’t know why one student is picked over the other student.”

Shreya Ravikumar, a freshman at MIT who graduated from Dougherty in 2021, supported this idea based on her experience going through the college admissions process. “There’s definitely an element of randomness to [the process], and you can’t predict based on certain points who is going to get into a college,” she said.

Many students feel the need to take a lot of weighted classes and involve themselves in many different activities just to check off another box on the list of things they think they need to do to get into their dream school. However, as Gonsalves explains, there is no “one-size-fits-all” formula for getting into an elite college.

“I found that a lot of students, both when I was here as a student and as a teacher, seem to think that there’s a specific formula that [guarantees that they’ll] be accepted. And that’s not always true. […] My mom is a teacher, and she told me she had a student who did everything right. They took APs and Honors, they were class president, they were part of clubs, they did community service, they were on a sports team — [all] because their one goal was to go to Stanford. They technically checked all the boxes, [but] they didn’t get in. And that goes back to what I was saying about how sometimes it’s random [and] that formula is not a guarantee,” she said.

Additionally, many students fail to understand that they don’t have to attend an elite college to be successful.

From her experience, Fox argued that students are far too focused on attending top-tier universities, “When students come to Dougherty, they have an idea that they have to go to a college like X or Y. I think there’s definitely a lack of openness to pursuing other options outside of the name-brand schools. The vast majority of people go to non-competitive colleges and [it] works out just fine.”

A study by economists Alan Krueger and Stacy Berg Dale in 1999 compared the earnings of individuals who graduated from highly selective colleges to the earnings of graduates of moderately selective colleges. The study revealed that 20 years after graduation, there was little to no difference in earnings between the two groups. A more recent follow-up study in 2011 also concluded that job earnings were not affected by the college that someone attended.

So instead of just having the goal of going to a big-name college, students should also consider which college would be the best fit for them.

Robert Gendron, an AP Calculus AB teacher, suggests that students should focus more on what major they want to pursue in college. “Just because the school has a good name doesn’t mean it has a good program for a certain major. For instance, my wife went to San Francisco State and people at Dougherty would be like, ‘Why would you go to a state school?’ But San Francisco State happens to have one of the best broadcast communication programs in the country,” he says.

Gonsalves discusses how it’s crucial to choose a college where you really feel at home, “I was an English major in college. I chose to go to California Polytechnic State University. And so a lot of people were saying, ‘Why would you, a liberal arts major, go to a polytechnic college where, typically, [students] specialize in STEM?’ It was because I loved the campus and because I felt at home. So I think that’s something big to consider for a lot of students. And then everything else tends to usually fall into place, whether that’s an Ivy League or not. If you can enjoy where you’re at, and enjoy what you’re learning, then that’s the right place for you.”

While there’s nothing wrong with aiming to go to a top-tier college, the whole college admissions process would be a lot healthier if students understood that it’s okay to not get in.

Fox agrees, “There’s really a lack of transparency in college admissions, meaning all you can do is really work as hard as you can and do the best that you can. When you’re going out there just know that we don’t know why one student is picked over the other student. Having that understanding to be okay with that rejection [is important]. It’s not a reflection on you as a person.”