Exploring 80 years of history and service at Camp Parks

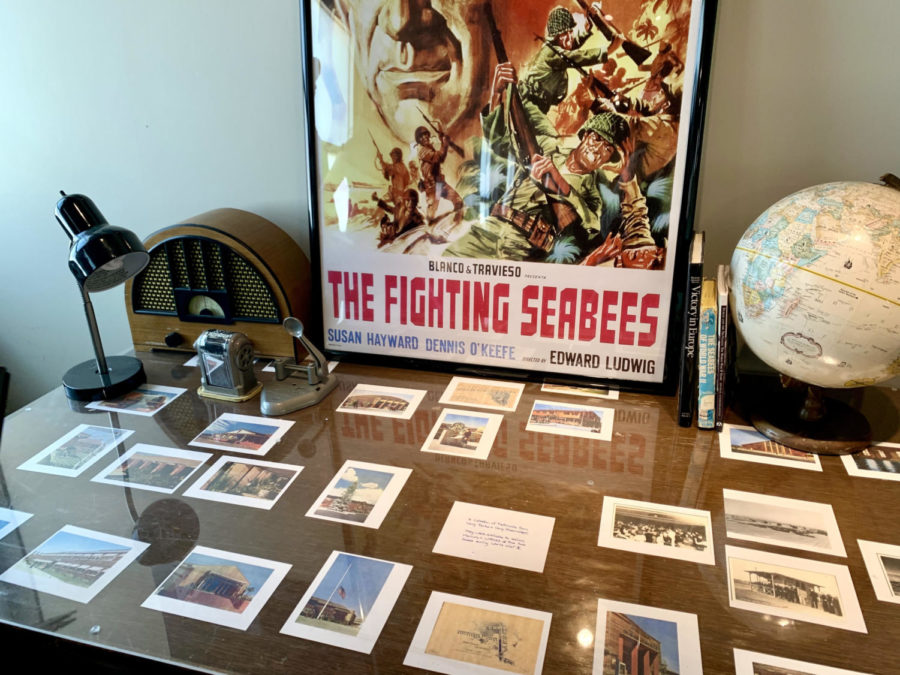

Service members, including those of the Navy’s Construction Battalions (“Seabees”), sent and received these postcards while stationed at Fleet City. The Seabees were later immortalized in the 1944 film “The Fighting Seabees” starring John Wayne, as shown in the framed poster.

October 25, 2021

Driving along Dougherty Road, you may have seen Camp Parks on your way through Dublin and became curious about the somewhat eerie fenced-off area that stretches past the street. Commissioned in 1943, Camp Parks, formally known as the Parks Reserve Forces Training Area, was originally home to the Navy Seabees who served in World War II. Almost 80 years later, Camp Parks still acts as a base and training area, but its mission has changed dramatically.

Initially, Camp Parks was one of three main military facilities in the area known collectively as Fleet City established during World War II to “house, train, deploy, recuperate and redeploy sailors to the Pacific,” as stated from information in the History Center. Camp Parks was the training and redeployment center for the Navy’s Construction Battalions (“Seabees”) who were tasked with staying ahead of the military’s engineering challenges, Camp Shoemaker was a Navy personnel distribution and separation center and Shoemaker Naval Hospital served as the local infirmary, according to the management plan for Dublin Camp Parks Military History Collections. The latter two facilities have since been dissolved, though their legacy still remains.

Since 2014, the Dublin Camp Parks Military History Center has exhibited artifacts related to Camp Parks’ contributions to World War II and other historical events. The self-guided museum exhibits are updated on occasion by volunteer docents to commemorate contributions made by soldiers. A current exhibit commemorating the 75th anniversary of “VJ-Day,” the surrender of the Japanese to the Allies during World War II, opened in Aug. 2021.

Other artifacts in the museum include insignia, historical uniforms, medical equipment and weapons. There are also documents and ephemera such as diaries, photographs, correspondence and more, offering a look into life as a soldier. These artifacts reflect the changing purposes of Camp Parks through the mid- to late-1900s.

One resident who helped establish the History Center was Steve Minniear, the volunteer historian of the City of Dublin and a 30-year resident. He has written two books about the role of Camp Parks during World War II and the history of Dublin, respectively, and also works with the Dublin Historical Society to give presentations about Camp Parks to the public.

“After Pearl Harbor, the US government realized that it had to fight this war in the Pacific and figure out a way to move troops and sailors out. So they quickly built [Fleet City] in part so that everybody in the Navy going to the Pacific would come out there and wait for their orders to go and fight,” Min said.

He explained that a 3000-bed hospital, 110 wooden, two-story barracks, recreation centers, a mess hall and rudimentary Quonset (metal and dome-shaped) huts were all quickly assembled to meet the needs of the 20,000 men.

The purposes of Camp Parks have evolved throughout the decades alongside the military.

During the Cold War of the 1950s, for example, government agencies interested in the effects of radiation conducted tests in the remote hills that surrounded Camp Parks. They created mock bomb shelters and, controversially, used live animal subjects in some of the experiments.

“One of the saddest things about that period was the radiation tests on animals. When radiation affects a living animal, the energy kills cells that can’t grow back. So scientists were testing how long of an exposure different animals could survive to give a sense of what could happen during [a potential] nuclear war,” he said. “They would have a radiation source and little pens for animals around a circle and then document the effects.”

He added that the scientists’ research papers can still be found online and dispelled the misconception that the radiation from the tests has lingered, assuring us that there were no radioactive animals still roaming Dublin’s hills.

Along with the evolution of Camp Parks through the ages, an increasing number of women contributed to the war effort in diverse ways.

“Women had an incredible role to play, initially in administrative activities or medical activities. One was Tommie Simpson, who worked at [Shoemaker Naval Hospital] during World War II and later helped establish the History Center,” Minniear said. “It’s been interesting to see how the military reflects society because it’s now almost fully integrated for women. There’s still more work to be done, but we can look back and see that progress.”

With Camp Parks’ early establishment as one of the largest training centers on the West Coast, population and suburban growth followed. The Tri-Valley was directly accessible by the Southern-Pacific Railroad, now transformed into Iron Horse Trail. In the ‘40s, Dublin farmers played an integral role in supporting the war effort with their food supply and blood drives with the Red Cross, according to the History Center. As time passed, Camp Parks became one of the main instigators of the transformations of Dublin, Pleasanton and Livermore from agricultural towns into cities. A History Center timeline shows that the Army re-designated Camp Parks as a training base in 1980, just two years before the incorporation of the City of Dublin.

Minniear explained that Fleet City spurred the construction of relatively cheap starter homes in Dublin along its highways. After soldiers were released from the bases, they decided to settle in the Tri-Valley permanently, in part due to the mild climate and increased employment opportunities. Population growth subsequently exploded.

Today, the Parks Reserve Forces Training Area is “the only active Army base in the San Francisco Bay Area with training facilities that include firing ranges, training land, simulations, and classrooms available to all military and federal organizations,” according to the History Center. There is also permanent housing for full-time employees and their families, while reserve forces are deployed to Camp Parks from all over the country. For example, the 325th Field Hospital, stationed out of Independence, Mo., conducted chemical warfare exercises in Aug. 1998.

“The Army Reserves forces became really important in Afghanistan and in Iraq because the first fighters [deployed in those wars] had to live someplace and get their supplies,” he said. “The Army Reserve folks tend to drive the trucks and do the medical stuff—the people that keep everything together. So after [the Sept. 11 attacks], all those people who thought they were only in the Army Reserve for a little while got called back. Camp Parks was [and still is] the place in the Bay Area for those reservists to get trained.”

From a naval base and hospital, to the site of government radiation experiments, to an Army Reserve training area, Camp Parks is a true skeleton of our past. However, this history is not lost. Camp Parks has breathed life into the Tri-Valley in the 80 years since its foundation. Though its initial purpose has long since dissolved, the bare-bones essence of the facility remains a snapshot in time, illustrating the constantly changing role of the military and the community we call home.

David • Dec 6, 2021 at 10:50 pm

To: Lauren Chen, Megan Dhillon, and Tessa Galeazzi,

Thank you for the great story and your time researching the history of Camp Parks. Local History is often lost and many do not realize what is around them. The Men and Women that have served at Camp Parks should be remembered for their service to our country. I am not a military person, I give thanks to them and to you for writing this story.