September 11, 2001: Who controls the narrative?

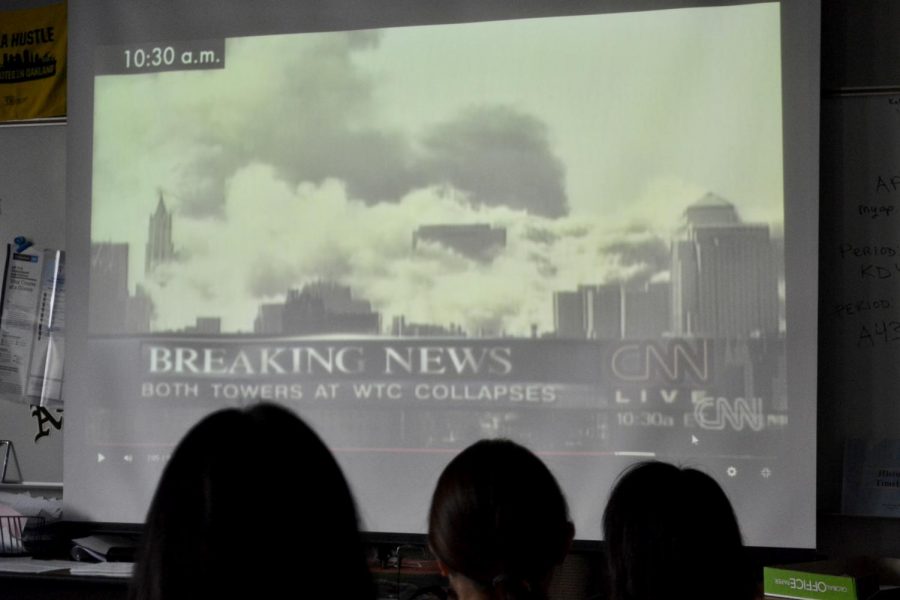

For many TK-12 schools in U.S., including DVHS, simplistic activities such as watching film and reading texts have become the norm for memorial studies on 9/11.

October 2, 2019

18 years ago, two towers came crashing down. 17 years ago, a never-ending stream of drone missiles began to rain down on the Middle East. As of today, millions of innocent civilians are dead in the name of false peace.

Seven years ago I was in a certain teacher’s sixth grade Core class. During the second month of school, our annual lesson on 9/11 commenced. We watched a video. Four years ago I was in that same teacher’s eighth grade Core class, and once again we watched that video.

Now, I’m in his AP U.S. Government class. The teacher was ready to show us that video, which I had already seen two times prior. The lights were turned off, the projector was on, his finger poised over the play button. But this time, as 17-year-olds on the cusp of voting age, we dared to question the script we had been taught. We didn’t watch the video this year.

No matter the teacher, we have all been provided the same narrative, the same perspective of 9/11 year after year, even as our intellectual abilities have matured significantly since seven years ago. There’s a reason U.S. history textbooks are designed to veer away from the present-day — it’s difficult to teach well without distortion from personal experience, political bias and Americentrism.

In our classrooms today, we’ve all but skimmed over the decades of U.S. intervention in the Middle East that came before 9/11, as well as President Bush’s War on Terror that came after.

In Osama Bin Laden’s Letter to America, he listed his rationale for 9/11. In an August memo, President Bush received information on a potential terrorist attack but remained inactive in taking preventative measures. These pieces of our history, while dangerous, should be carefully analyzed to show newer generations how extremist plots and American politics can intersect.

Every year teachers show varying editions of what is essentially the same video on 9/11: the Twins Towers crashing down, panicked news broadcasters and New York City in ruins — all overlayed with the soundtrack of gut-wrenching screams. These images of disaster — the only knowledge I had of 9/11 for a long time — trigger an emotional response in students supposedly learning from them. Total obliteration evokes immense fear, grief and distress.

9/11 is a hard topic to discuss. It’s a jaded, tangled mess. To understand it, you have to unravel Middle Eastern countries, religion, extremists, United States, nativism, theocratic regimes, oil dependency, all on top of the emotional trauma Americans have associated with this event. It’s understandable as to why teachers show a video, trusting in its neutrality.

But I came to an important realization when no one raised their hands when asked: “Were any of you alive during 9/11?”

I realized that time has gifted us with a tabula rasa, a clean slate. It’s been 18 years since this event, and the Class of 2020 is the first group to have not lived at the time of its occurrence. Yes, 9/11 was a tragic event. Yes, it is important to American history. But that doesn’t mean we can’t talk about it, study it, question it. As the famous phrase goes, “dissent is the highest form of patriotism.”

Part of this gap in knowledge is the way College Board and other educational institutions set instructional priorities: on the AP United States History exam, 15% covers the time period from 1945-1980 while only 5% spans from 1980 to 2019. Other history class experiences have taught me the importance of perspective, nuance and reasonable doubt. With the historical importance of an event like 9/11, context is vital but very much missing.

For most of us at Dougherty Valley, we are used to living side by side with different religions and cultures, which offsets these induced prejudices. But that may not be the case for others outside of our community. In the eight weeks that followed 9/11, the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program saw a statistically significant increase in hate crime toward people of the Muslim faith.

Why, after 18 years, are we still afraid? Why are we throwing bombs year after year at blurry targets and declaring victories over the flattened towns of other countries’ civilians? Only three days after the attack, Congress voted to give the President unlimited power. The Authorization for Use of Military Force, or AUMF, was overwhelmingly popular. It didn’t just have bipartisan support — only one person in both chambers of Congress voted no, while 618 voted yes. This became the beginning of Bush’s War on Terrorism, causing more than two million reported casualties. When the Middle East became a battleground, millions of people went into poverty, having no choice but to pick up ammunition and join extremist organizations, all in exchange for protection and survival necessities.

Today, withdrawing from the Middle East would cause a power vacuum that destabilizes the region. For the time being, the United States will have to continue its wars in the Middle East. However, we should move from an active to a more supporting role. Whether you believe that the AUMF violates Congress’s right to declare war or not, the legislation has legitimized bombings, troop deployments, military detentions and wars in 20 different countries.

One reason Americans continue to give AUMF power is that as a nation, we are more afraid of how we might be hurt by the Middle East than we are indignant for the innocent lives that get thrown away in the wake of its invocation. In the back of our minds where irrationality lurks, we’re afraid that without the aggressive executive actions that AUMF allows, our country will collapse as the Towers did 18 years before. We choose to willingly ignore that domestic terrorism is a much larger threat to American welfare than its international cousin. No AUMF-authorized airstrike can save the American teen from the dredges of the Dark Web: only independent thought and the questioning of presented narratives can prevent them from radicalization.

So how do we fix this problem that is rooted in our educational system and worsening every year on Sept. 11?

To be honest, I can’t say for sure. But I know we need to dedicate more time to this event besides the one historic day. Terrorism is a multi-layered concept that extends far beyond radical interpretations of the Quran. We must discuss the factors that cause and perpetuate terrorism: war, poverty, resentment. When the vicious cycle is finally recognized, one day there will be potential to break free. But these intricacies can’t be covered in a single day, especially when people may want to mourn in peace. The clustered mess of events that redefined global security deserves their own detailed unit, like Manifest Destiny, the Revolutionary War or the 1929 Wall Street crash.

Today, America is still entangled in Middle Eastern affairs. Although it’s a tough pill to swallow, our country helps terrorism take root. As we grow older, we must take the initiative to inform ourselves, our peers and our mentors to hold politicians accountable for the chaos that America fostered at the turn of the century.

The reason Americans continue to give AUMF power is that as a nation, we are more afraid of how we might be hurt by the Middle East than we are indignant for the innocent lives that get thrown away in the wake of its invocation. In the back of our minds where irrationality lurks, we’re afraid that without the aggressive executive actions that AUMF allows, our country will collapse as the Towers did eighteen years before. We choose to willingly ignore that domestic terrorism is a much larger threat to American welfare than its international cousin. No AUMF-authorized airstrike can save the American teen from the dredges of the Dark Web — only independent thought and the ability to question presented narratives can prevent them from becoming radicalized.

So how do we fix this problem that is rooted in our educational system, expanding every 9/11? To be honest, I can’t say for sure. But what I can say is we need to dedicate more time to this event besides the one historic day. Terrorism is a multilayered concept that extends far beyond radical interpretations of the Quran. We must discuss the factors that cause and perpetuate terrorism: war, poverty, resentment. When the vicious cycle is finally recognized, there will be potential to one day break free. But these intricacies can’t be covered in a single day, especially when people may want to mourn in peace. The clustered mess of events that redefined global security deserves their own detailed unit, like the Revolutionary War, Manifest Destiny, or Stock Market Crash.

Today, America is still increasingly entangled in Middle Eastern affairs. Although it’s a tough pill to swallow, our beloved country plays a part in terrorism taking root. As we become young adults, I hope we take the initiative to inform ourselves, our peers and our mentors, so that we can begin holding politicians accountable for stabilizing the chaos that America fostered at the turn of the century.

Edited by Kavin Kumaravel and Sanjana Ranganathan, opinions editors, and Daniel Shen, editor-in-chief.