What It’s like to Grow up White

Samuel Minioza

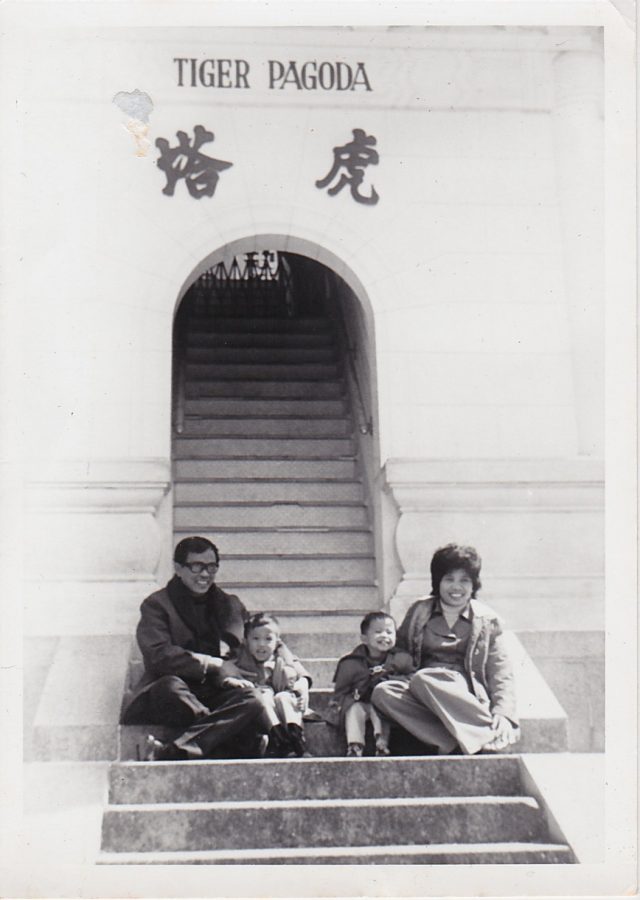

My Lola and Lolo (Grandmother and Grandfather in Tagalog) sitting with my Dad and Uncle in Hong Kong after leaving the Philippines to flee martial law. That would be one of the last times they were in the Philippines for the rest of their lives.

June 12, 2021

I’m white.

For anyone who’s looked at me before, that sounds almost like a ridiculous statement. My skin is tan, my nose is flat and I have almond shaped eyes. For even someone who’s heard of who I am, it seems impossible that I could be white.

I’m the vice president of Dougherty Valley High School’s Filipino American Club, I practice and perform traditional Filipino dance and I study Philippine political and cultural history. On paper, I seem to be the standard, if a bit outgoing, Filipino. A true “Asian American.”

But humans on their surface are so often deceiving. In reality, I don’t speak or understand Tagalog, the dialect of Philippine languages both my parents speak.

I don’t like a lot of Filipino food, in fact I threw up as a kid whenever I ate Filipino food. I’ve never sent or received a balikbayan box (boxes of gifts from or to Filipino relatives of treats, money and other small items), nor have I even been to the Philippines.

Thus, I’ve always felt distant from my Filipino identity. There seems to be an impassable gap eroded by the lack of experiences and qualities that would traditionally make me “Filipino;” a gap that seems to characterize a different kind of identity altogether separate from my blood. It was around sixth grade when I realized I was “whitewashed.”

Being whitewashed for me is twofold. Externally, being whitewashed means I get to benefit from all the privileges and opportunities of my parents in essence being white. White means stable and good socioeconomic status, so I get to go to a good school and I get to eat American food that people don’t make fun of me for.

It means that my parents don’t burden me with the same typical “Asian standards” of educational attainment, and that I have the opportunity to do what I want. In essence, to be white is to be treated like the world is your oyster, and that’s not such a bad thing.

Internally though, being whitewashed is a more souring experience. It means that in place of my own ethnic heritage I am abashedly Americanized. I am placidly typical, with no true heritage I can call my own because of my lack of experience with it; I can’t easily say that I’ve experienced any stereotypically Filipino experience.

In their place I hold only white ones that are in line with the American norm, internally and therefore culturally. Being whitewashed also means a void of heritage and of identity. When I think about Filipino dances and traditions, I don’t see them as a reclamation of my own culture. I see them like any other foreign culture: beautiful, but distinctly not mine.

However, race and identity is much more than just the experiences we individually have. Identity is often collective, and in part is the brotherhood and appreciation of oneself gained from the comfort of knowing people like us. In a word: culture.

But when the world looks at me, they don’t see a white man; they see my skin. The world seems to demand that my culture comes down to blood, not experience. I should be Filipino because I look that way, because my parents were born that way, because I am that way.

It’s an unfortunate truth, but the reality is that most people lend much more credence to someone’s skin color as it relates to their culture than they would like to think. If you look Asian, well, you are Asian to most people. But what does that really mean? Ask yourself, what does it mean to “look Asian?” More specifically, which Asian Americans do you call Asian and which do you not?

The reality is that while it is natural to identify Chinese and Japanese Americans as Asian, when people see Indian Americans, we call them Indian, not Asian. Not because they’re any less representative of the Asian stereotypical identity (they might be the most representative in fact), but because “Asians” aren’t supposed to be brown or pray to Ganesha or Shiva, two Hindu Gods.

When people see Indonesians, most people’s first reaction is to ask them where they’re from. Not because they’re any less “Asian” than anyone else, but because “Asians” aren’t supposed to wear kopiahs or kerudungs, the traditional attire of muslim Indonesians.

The hard truth of the matter is when people say someone’s Asian, they mean to say that they’re Chinese, Vietnamese, Japanese or Korean; the ones who are most prevalent, who look the most similar in color and in appearance, who are the most “Asian” because of that. It means that if you look Asian, you have fair skin, not dark like mine.

Yet what distinguishes me even from Asians who are separated from the Asian American identity is that I’m excluded from my Pinoy (another name for Filipino American) identity as well. When most Filipinos are excluded from the Asian American identity, it’s easy to take pride in their own ethnic heritage. It’s natural to be proud of being Pinoy, in having an ethnicity distinct and just as beautiful as any other.

But to take pride in being Pinoy means to harken back to common experiences; because frankly, if commonalities aren’t the backbone of culture, then what is?

Commonalities for Filipino Americans means a rags to riches story for your parents or for yourself, and even more than that means that you fit neatly into the stereotype of the Filipino immigrant. I know I’m supposed to have eaten rice with every meal, to have my parents be frugal because they didn’t have much. I know I’m supposed to have sung karaoke, that I’m supposed to speak if not at least understand Tagalog.

I know I’m supposed to watch The Filipino Channel (TFC) with my Lola (grandmother in Tagalog), that I’m supposed to have been told Dinuguan was chocolate soup or some common lie. I know everything I’m supposed to be, and I’m anything but that.

In this stupor of disillusion, I don’t feel the joy of having my parents raise me like I’m white. I don’t internalize the happiness and opportunities I’ve had because my parents are wealthy and because they raised me white.

Instead I am forced to recognize the results of my parents’ dream of prosperity for their children and the identity they sacrificed to attain it. I get to look in the mirror to see a white man staring back at me while the whole world insists I am brown. In these moments, I don’t enjoy the luxury of being Americanized and typical, I feel the burden of being without an identity that I can truly identify with.

So when I go to my cousin’s house, I don’t feel my “white privilege.” I instead get the privilege to watch as they push me out of the prayer circle when we bless the food because my family and I are different. When I’m with my friends, I don’t feel pride in being Pinoy.

I get the luxury of not being Asian, of being called a “Filipino”; because I’m not like them, Korean and Chinese Americans who are distinct from me and “more Asian” than me. And when I hang out with white people, the people who are supposedly most like me in kind and in social privilege, I become their token orient like any other Asian, I’m unwelcome.

Someone once asked me, “So what you’re whitewashed? Just because you don’t relate to what other Filipinos have doesn’t mean you’re not Filipino.” To me, therein lies the problematic assumptions we make about our view of culture and race.

We tell ourselves that our definitions of culture aren’t simplistic or rigid anymore, no longer one dimensional. But denying the truth doesn’t make it any less pertinent.

It is undeniable that while we ought to and say that we judge people on more than just the color of their skin, we still do to a huge extent. It is absolutely false that people are accepted into a community on blood alone. Rather, people tend to be accepted or excluded based on the way they act and the way they are.

That seems on its face so obvious, of course someone within a community should generally identify with a clear set of traits or experiences to be a part of that community. If you’re in the knitting club, you knit. If you’re in the World History discord server, you like history.

But in the context of culture, we consistently contradict ourselves. If someone is adopted, we tell them they still remain ethnically tied to their blood, despite the fact they were likely raised in the household and therefore in the culture of another ethnicity. If someone is whitewashed, we tell ourselves that these people are just as much a part of their ethnic culture despite the fact that by definition they hold nearly nothing in common with the community.

We assume these things because it is impossible for many to fathom that someone of a certain skin color could share nothing in common with our ideas about people of that skin color. We stumble over ourselves in an attempt to reconcile the exceptions we make to cultural inclusion because of our preconceived notions of people with such blood.

Now I am not going to say that we shouldn’t shape ethnic identities based on commonalities. It is of course clear that we should base culture on the experiences of the majority. If it is based on a minority experience instead, it is by definition not representative.

The issue becomes that we continually seek to define ourselves and others by these labels entirely. We seek comfort in knowing we are Asian, that they are Filipino. These labels are comforting in their holisticness and their ability to summarize us simply in a complex world. It is easy to understand people if they are simpler.

But the reality is that this reductionism is a hammer that blindly turns all cultural issues into nails without regard. The truth is that the rigidity of ethnic identities born from its simplicity pushes out many like myself who take no solace in the expected experiences of their identity. Not everyone fits the standard archetype of the Asian American. Not everyone is the stereotypical Filipino.

It is such a powerful and visceral thing to be ignited by one’s identity, to feel at home within a culture. Taking pride in a world that frequently slanders you for being who you are is one of the greatest joys in life.

But it’s important to remember that we often neglect the flip side of that coin. We so often fail to understand that humans defy the labels and identities we seek to portray them as in countless ways.

I’m white, but I don’t look it. I’m Asian, but I’m not called it. I’m Filipino, but I don’t feel it.

So what am I?

Samuel Minioza • Jun 13, 2021 at 10:59 am

Very cool article interesting perspective they must be so cool irl i would die for this writer btw