Reactions to Black Lives Matter protests in Tokyo expose Japan’s hidden discrimination

Athmika Sriram

Although Japan’s population is becoming more and more diverse, it still remains a majority homogenous nation.

October 31, 2020

Black Lives Matter protests took place in Tokyo this September, which caused backlash from Japanese citizens and raised questions about Japan’s treatment of not only people of color, but foreigners and outsiders as well.

The protests were started by a team of activists known as Black Lives Matter Tokyo, led by Jaime Smith who was inspired by America’s activism, but upset that she could not directly be involved in the US protests. According to Smith, the original intent of these protests were to “stand in solidarity with the protestors in the USA.”

The first protest was expected to have 1,000 people in attendance, but ended up with almost 3,000 people of various ethnicities. The movement has now expanded, even hosting a live stream YouTube event called “Harmonic Wavelength” on Sept. 6 that put a spotlight on Black artists and their music.

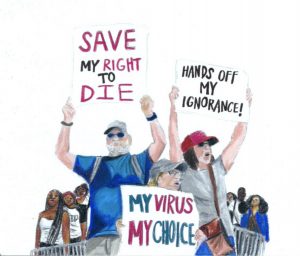

However, despite all this support, the movement faced some backlash from others, especially due to its attempt to call out Japan’s own anti-Blackness.

Bianca Hillier, a writer for The World, explains that “critics accused marchers of ignoring the coronavirus risks and online commenters argued that racism is an American issue — not a Japanese one.” One person even tweeted, “I won’t feel any mercy if these people are told to get deported by the local Japanese.”

This denial of the existence of racism in Japan isn’t an isolated incident.

Take, for example, tennis star Naomi Osaka. On Sept. 20, Osaka, who is half Japanese and half Haitian, was announced the champion of the US Open at the age of 22. Osaka has been a strong advocate for movements like BLM, even dropping out of the Western and Southern Open tournaments after the shooting of Jacob Blake, a Black man, by White police officers in Wisconsin. In fact, after the US Open, Osaka encouraged people in Japan to join a Black Lives Matter march, perhaps one of the reasons for the protests in Tokyo.

Chiyoko Kobayashi, who lives in the Gunma prefecture of Japan, said, “When Naomi Osaka wore a mask with George Floyd’s name while playing, I think lots of Japanese viewers felt more familiar to that movement. Many of her fans feel proud of her actions and support for BLM.” *

But this did not go without controversy. After she made a tweet in support of the BLM movement, one person responded by saying, “Naomi Osaka does not seem to be the pride of Japan. This is my own personal view after all, but I now recognize her as a terrorist.”

Before looking at the current state of these sentiments though, it’s imperative to understand the root in which these ideas were founded. Japan has historically been a homogenous nation. In order to avoid the influence of European countries, a powerful shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu, implemented an isolation policy known as the Sakoku Edict of 1635. The edict closed Japan to foreigners and locked his citizens in the country. This edict, along with others (like the Portuguese Exclusion Edict of 1639), were strictly enforced until 1852 when Commodore Matthew Perry forced the end of the edicts. The country was closed for almost 220 years, creating the homogeneity of Japan today. Since then, the country has become a world power and is integrated into the global economy, but this hasn’t erased the homogeneous nature of the country’s demographic.

For example, a report by Mizuho finds that in 2018, a mere 2% of the Japanese population consisted of foreign residents, automatically making anyone who is not Japanese a minority. Yasuma Fujinaga, a professor of American Studies at Japan Women’s University, puts it starkly: “In essence, Japanese people don’t have a lot of experience of seeing other races so they don’t think racism exists.”

And it seems that BLM Tokyo, Naomi Osaka, or anyone else who attempts to call out Japan’s racism is criticized for doing so.

John G. Russell, a writer for the Japan Times, explains that “U.N. Special Rapporteur Doudou Diene’s 2006 report on racism and ethnic discrimination in Japan was largely ignored by the Japanese media and severely criticized by right-wing commentators.” The report had found that officials in Japan not only ignored xenophobia, racism and discrimination, but “discriminatory statements against foreigners are made by some public officials. The police disseminate posters and flyers in which foreigners are assimilated to thieves. Posters by extreme right political organizations asking for the expulsion of foreigners are tolerated.”

Thus in reality, racism isn’t nonexistent; it’s just not addressed. As Kobayashi explains, “There is racism in Japan especially seen among elderly adults older than 60 years. For example, there are many people in Japan who are not fond of Chinese and Korean people and are often upset by tourists that enter the nation.”

This racism can also be seen with those who are biracial as well. Kobayashi, whose son Sean is half-Japanese, recalls incidents where Sean was discriminated against due to his race. In one of these incidents, older kids in Sean’s elementary school told him to “go back to where [he] came from,” referring to the United States.

However, the foreign minority is growing. In an article for the Japan Times, writer Magdalena Osumi quantifies that although the 2% population of foreigners may seem small, “the number of foreign residents in Japan had risen 6.6 percent at the end of 2018 from a year earlier, to reach a record high of some 2.73 million.”

And because of this increase in foreigners, Japan is slowly reforming. For example, in an article for the Japan Times, writer Debito Arudou explains that among many other reforms, “a hate speech law was enacted in 2016 to protect foreign nationals from public defamation.” As a result, Arudou wries that “xenophobic rallies, once averaging about one a day somewhere in Japan, went down by nearly half. Racialized invective has been softened, and official permission for hate groups to use public venues denied.”

Kobayashi furthers that “[the] Japanese government is actually planning to invite more immigrants as workers than ever before.” Because of this increase in immigration, she explains that “in Japan, there are various TV shows that introduce immigrants or visitors in Japan through interviews or documentaries. These help Japanese people understand different cultures, making a good impression on Japanese viewers.”

Overall, whether they face controversy or not, movements like Black Lives Matter Tokyo are helping to put Japan on the path to creating change. As Osaka puts it, “If we can get [the message] across, then Japanese people might be willing to speak up for us more in places where we cannot. Because we’re all one community.”

* The interview with Chiyoko Kobayashi was originally conducted in Japanese. The quotes used in this story are a translation kept as close to the original meaning as possible.