Health care workers face dangerous COVID-19 conditions

A substantial amount of health care workers reported that they experienced mental health disorder symptoms after working with COVID-19 patients in China.

May 3, 2020

As COVID-19 cases in the U.S. continue to increase, health care workers around the world are working hard to keep citizens healthy while struggling to care for their own physical and mental health.

Whether doctor, nurse, physician or clinician, working in hospitals has become more of a concern than ever, since being on the frontline means constant interaction with the virus and extreme risks of infection. A report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that 11% of cases in Oklahoma, 20% in Ohio and 25% in Rhode Island are health care workers, totaling to almost 5,400 cases across the country overall. These numbers continue to grow every day.

As the pandemic worsens, the demand for resources, in particular surgical masks, has surged as well. The government’s Strategic National Stockpile of medical supplies consists of almost 42 million masks, which unfortunately only accounts for 1% of the 3.5 billion masks that are currently needed at pandemic levels. And this lack of masks means that nurses and doctors no longer receive the resources and protection they need.

Susan Puckett, a physician assistant at the Boulder Medical Center claims that she was given one N95 mask, meant to be single-use, which she is expected to keep until it breaks. From one patient to the next, she is forced to wear the same protective equipment, only making the chance of spreading the virus even higher.

Puckett is not alone. Across the country, hundreds of anonymous workers report being told to only save masks for patients. According to the CDC, reusing masks puts health care workers at risk of contact transmission, cross contamination between patients and more.

In addition, according to BBC, many of the masks delivered to health care workers have in fact expired, but underwent “stringent tests” by the Department of Health and Social Care and were re-disinfected, then given a new shelf-life. The Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) also temporarily approved the emergency use of non-medical protective equipment that were approved by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) as well as expired masks and respirators that were decontaminated.

Mask or no mask, many of these health care workers don’t have the ability to determine if they are actually infected. With the approval of a new test with an efficient 45-minute administration period, the public is attempting to get tested. Unfortunately, this detracts from already-limited testing sources.

According to the Washington Post, “many health officials remain concerned that testing sites will be inundated” and everyone who wants a test being tested “will lead many with mild cases to squander finite resources.”

Diana Torres, a nurse at Manhattan’s Mount Sinai Hospital, said to Business Insider that these limitations mean health care workers no longer get tested. “Even though we’re sick, we have to be really sick in order for us to get tested,” she said.

The daily sacrifices of health care workers also lead to unfortunate effects on mental and emotional health. In the United States, those treating COVID-19 patients have spoken out about their heartbreaking experiences with those affected and the extreme changes to their daily schedules due to the precarious nature of their work.

“It’s just a matter of time before I bring [COVID-19] home to my children,” Heidi Flores, a nurse from Southern California, said. In an interview with ABC7, she said she chose to self-isolate from her husband and seven children as she works every day of the week. “This is the hardest thing I’ve ever done,” Flores said.

A travel emergency room nurse named Paige (last name redacted for anonymity) told Insider that “some nurses were being asked to fill out their advance directives or do end-of-life planning in case they contract the new coronavirus and die.” With Paige being forced to reuse PPE over multiple shifts, she knows how easily the virus can be contracted, yet still feels obligated to put her patients first. “If I were to get really sick, my sisters know I don’t want to take a ventilator from someone else who may need it.” she said.

Paige has expressed her frustration with the lack of emotional support and PPE, voicing the opinion of frontline health care workers across the nation by saying, “We’re not sacrificial lambs. I didn’t become a nurse to be a martyr.”

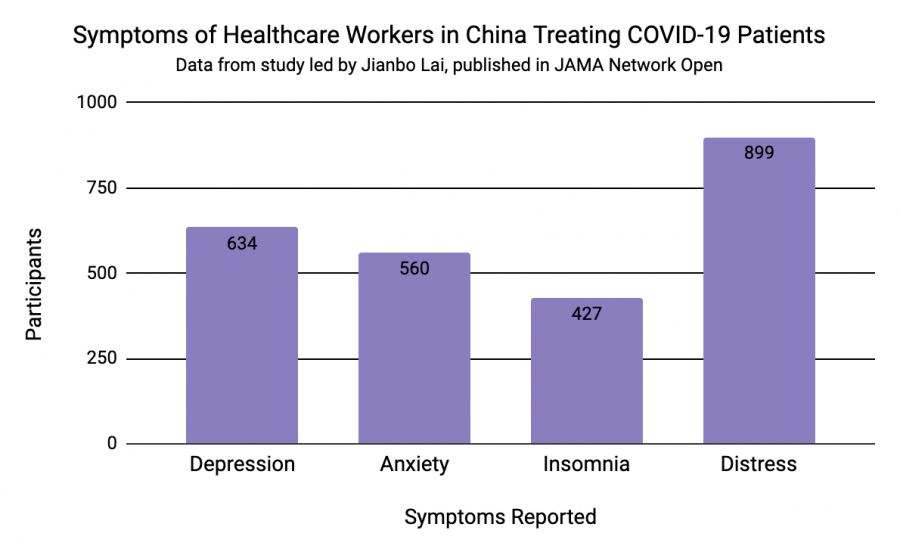

A study from March 23 led by Jianbo Lai and published in the medical journal JAMA Network Open analyzed the mental health conditions of health care workers treating COVID-19 patients in China. Lai and others conducting the survey found that “among Chinese health care workers exposed to COVID-19, women, nurses, those in Wuhan, and front-line health care workers have a high risk of developing unfavorable mental health outcomes and may need psychological support or interventions.”

The research team used a multitude of tests and questionnaires to survey participants’ symptoms of “depression, anxiety, insomnia, and distress,” and concluded that “A considerable proportion of participants reported symptoms of depression (634 [50.4%]), anxiety (560 [44.6%]), insomnia (427 [34.0%]), and distress (899 [71.5%])” out of 1257 surveyed health care workers in 34 hospitals.

The Veterans Affairs National Center for PTSD put out a list of self-care behaviors for health care workers in the time of COVID-19. Among the suggestions were “regular check-ins with colleagues, family, and friends,” and “fostering a spirit of fortitude.” Though uplifting, the advice does not align with health care workers’ 12-hour shifts or seven-day workweeks.

Even though therapists and other mental health professionals are holding free or reduced cost online counseling sessions, citizens have failed to empathize with what has become the stressful daily routine for frontline COVID-19 workers. Many must individually tend to multiple infected cases in extremely understaffed hospitals. Doctors and nurses have even become the surrogate family for their patients when visitors are barred from seeing their family members. At the same time, health care workers are forced to isolate themselves from their own family.

Additional “self-care behaviors” (also from the list published by the Dept. of Veterans Affairs) claimed that healthcare workers should avoid “working too long by themselves without checking in with colleagues” or “working ‘round the clock’ with few breaks.” These examples further show the disparity between an outsider’s perspective on the crisis and the new reality that healthcare workers must face every day.

Health care workers, those meant to keep Americans safe, ultimately are the ones whose mental and physical health are suffering the most. However, as long as citizens practice social distancing and take extra caution, millions can stay healthy and a slight burden can be lifted from indispensable doctors, nurses and other caretakers.