“A Glitch”

Featured artist: Jennifer Gee

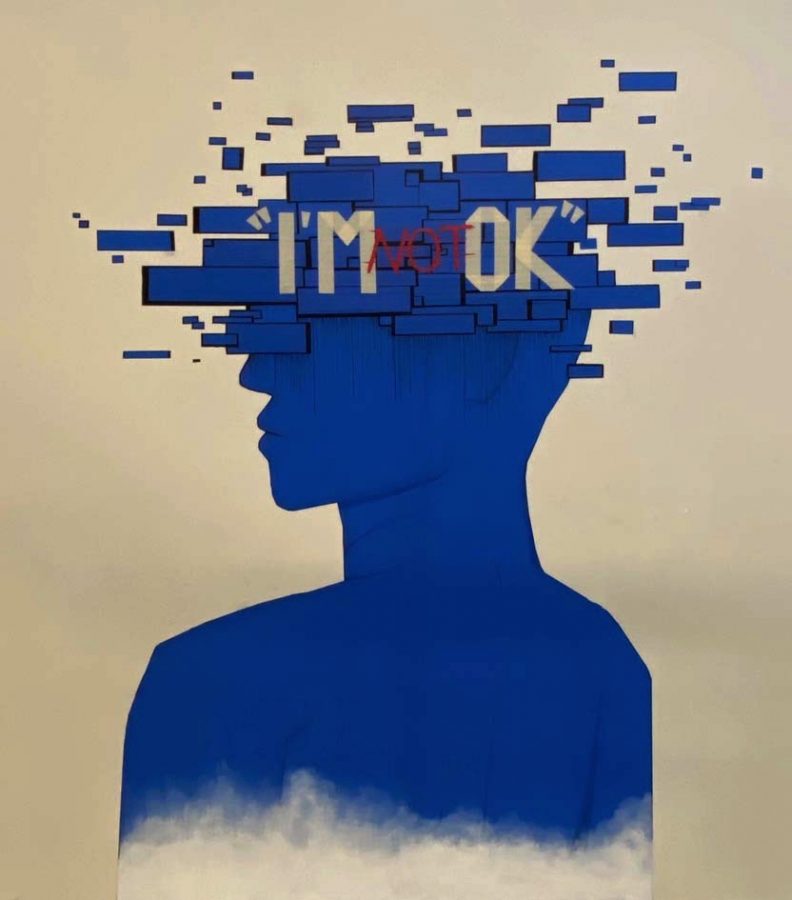

Seniors Jennifer Gee, Aarushi Vekaria, Tracey Ley and Tejal Thakral created the piece outside the 1000 building. Blue masking tape forms the silhouette of a human head that explodes into glitches.

April 29, 2020

The decision was obvious for senior Jennifer Gee: her topic would be mental health. It seemed clear, almost essential, for it to be so. Looking around herself, Gee saw her classmates struggling with heavy workloads, bearing up under stress of being a high school student — and a human being. That was the key: that everybody was going through some difficulty.

“Even though you may be okay on the outside, you have glitches on the inside,” said Gee. “Our intent was to showcase our interpretation of mental health by creating a figure that is genderless and faceless.”

The image takes up an entire wall in the 1000 buildings, towering over the students almost overwhelmingly. It’s a strange contrast, and one that makes a lot of sense: the tape art imitates the looming presence of stress, while also conveying the prevalence of being scared and uncertain.

“By doing this type of “graffiti” art, I guess you could say, I can reach out to a bigger audience,” said Gee. “[Our group] said, go big or go home. Try to make the biggest thing possible because none of us no one in my group has worked to that type of scale.”

Their first step was sketching out a rough draft; the second was plastering the tape to the wall — a “very hard,” time-consuming process. Gee and her teammates layered tape to create a 3D effect and used Posca paint markers to delineate the intricacies of the glitches.

While the tape art communicated a message custom-made for DV, mental health is a common theme through Gee’s work. One piece, for example, meticulously produced in black pen, portrays a stark human arm filled with gears and robotic components, made when Gee was feeling “disconnected” and “distant.”

“It’s just the social stigma around mental well-being and having that 4.5 GPA, taking five APs, just trying to flex on each other with academic prowess,” said Gee. “It just doesn’t lead down to a happy road.”

Making art is Gee’s method of staying on her own “happy road.” Sometimes she’ll find that her feelings are difficult to put into words — as if her emotions were a confounding puzzle of rectangular glitches, like portrayed in “I Am Not Okay.” By drawing, usually with her favorite medium of pen and pencil, Gee releases her pent-up emotions onto paper and examines them from there.

“I’ll get a sense of relief and understanding of what I’m feeling,” said Gee, who has been making art for as long as she can remember. “And if people ask me how I’m doing, I’ll just show them a piece of work that I did at the time. And, like, try to interpret as well.”

Gee is careful to emphasize that one doesn’t have to “be okay” to be on a happy road. Rather, it’s about maintaining a balance and finding the necessary support system.

“The support system here [at Dougherty] is amazing and great. It just leads up to the fact that people need to reach out — and I don’t think people will do that,” said Gee, who has struggled with depression and insomnia herself.

This all circles back to stigma. Feeling overwhelmed, then feeling judged for being overwhelmed, and then feeling overwhelmed by judgment — it’s a damaging cycle.

At school, Gee believes that teachers can play an integral role in easing their students’ mental health by lifting stigma around the issue: “Say, it’s perfectly okay to not be okay. Just openly express that teachers themselves have bad mental health days as well. And that it’s a completely human thing.”