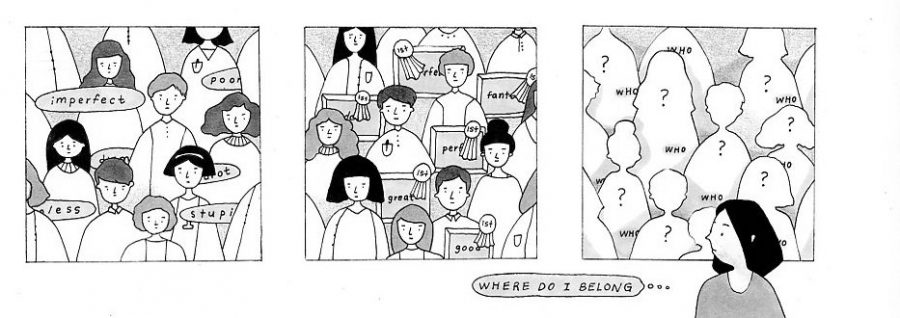

The perils of categorization

Categorization, when improperly enforced, can have devastating effects on individuals and the more expansive society they are part of.

November 19, 2018

When I was younger, my self-perception was limited to essentially one question: which Hogwarts house would I be a part of?

My friends were sure I would be a Ravenclaw, but I took every online quiz I could find until one validated my opinion: Slytherin. Houses in Hogwarts, lineages in Greek mythology, careers in the Giver, factions in Divergent — the books that I have buried myself in have fed my appetite to categorize myself. Even as I grew out of my love for young adult books, however, I still felt like I needed to put myself in a box to make sense of myself, which I continued to do, largely through personality tests and other people’s expectations.

When I was in third grade, my school administered a test to determine who would enter the Gifted and Talented Education (GATE) program. I sat in the cafeteria for three hours and solved seemingly meaningless questions about napkin folding and word analogies. My fellow testers and I thought nothing of it then.

But months later, results were delivered, and in my extraordinarily cutthroat elementary school (yes, those exist, believe it or not), those scores felt like everything. While we had appeared more or less in the same intellectual basket before, with our fascination with “Junie B. Jones” books and similar performances on our weekly homework (literally just a crossword puzzle and spelling), a gap began to grow between those who had met or nearly met GATE standards and the rest of the students.

Those who had tested into GATE were filtered into specialized geography and finance after-school programs, asked to volunteer and tutor for teachers and encouraged to compete in Math Olympiad and MathCounts.

I remember my bunch of GATE kids, all of us keeping our noses just a tad bit higher in the air, convinced of our own apparent superiority over the rest (yes, I do realize how ridiculous that sounds. Hindsight is 20/20). It wasn’t some ridiculous two-month long boast that fizzled out either — the kids who tested GATE stayed GATE; they were the 4.0 GPA, perfect attendance, hyper-focused, perfection-demanding, slightly obnoxious students throughout all of elementary and middle school and into high school.

For me, the moment was a life-changing one. I discarded my dresses and my dolls, and decided that I would characterize myself as the “smart” one.

Yet the fact remained that even though our grades differed, it’s not like all the smartest people tested in; far from it, actually — there were a lot of raised eyebrows at certain individuals. However, those individuals, whose grades were equal to or in many cases lower than those of their classmates, more often than not became the most “successful.”

So what was up with the tests: could they predict future success or narrow down some intrinsic quality of intelligence in students that no one had ever noticed before with problems about napkins?

The truth is far from that. In the field of psychology, there’s a concept called labeling theory: labeling something doesn’t only change the perception of that subject but also changes the subject itself. For example, when Harry Potter was sorted into Gryffindor, that label would not only categorize him according to his characteristics, but also shape his characteristics so they fit with the ‘“courage before all else” label.

In 1965, social psychologists Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson conducted a study to prove this. They told teachers at an elementary school that a set of students had been classified as “academic bloomers” based on their scores on a test; however, this test didn’t actually exist exist and the students were actually chosen at random.

Even though there was no scientific or educational basis to labeling these students “bloomers,” the researchers found that the “academic bloomers’” IQ scores outperformed their peers’ by 10 to 15 points by the end of the school year, even though their performance and scores were seemingly indistinguishable from “non-bloomers” at the beginning of the year. This led the research team to come up with the Pygmalion theory: when people have increased expectations for a person, such as a label, the aforementioned person tends to perform better.

It is impossible to reinforce how groundbreaking this was and still is. Just because a student was labeled as an “academic bloomer” at that school, their circumstances and performance drastically changed. Similarly, people in my elementary school were labeled GATE, so their academic outlook changed. The whole situation can be summarized as “I was labeled, so I became, so I am.”

In context of the study, the label was beneficial — calling the student a “bloomer” made them succeed, a victory in almost anybody’s books. However, it is so easy to see how this could be a double-edged sword. Labeling someone intelligent isn’t the worst thing you could do, but imagine the effects of labeling someone “poor,” “disadvantaged,” or “stupid.” It could be devastating.

Labels are something that we don’t often address, especially within the context and confines of Dougherty Valley.

The overarching example is the labels we place on DV itself; this is a demographically diverse high school with over three thousand students — it seems obvious that each student’s perception of DV would differ simply because their background and experiences do.

Yet, the most common perception of the school is one of uncontrollable cheating, extreme stress and daily late-nighters.

Obviously, there’s some truth to that.

However, the exacerbation of these conditions is due to people rising — or sinking — to meet those labels. I’ve heard dozens of conversations in which students boast about getting three or four hours of sleep.

Despite the common opinion, Dougherty isn’t that bad. Sure, it can be tough, but if you look at actual statistics, we aren’t that different regarding tests and social situation from other high schools. Most of the students that complain about sleep deprivation and stress aren’t just reacting to the apparent grievous conditions of the school; they’re guided by the label to see the school according to the aforementioned label. Dougherty isn’t stressful because the curriculum is significantly more difficult — it’s stressful because we think it’s stressful. Therefore, we make it stressful.

Grades are another label; we go around judging people by the A’s and B’s and C’s and F’s they earn. We’re labeled by our grade-point average, our SAT score, the internship we got or non-profit organization we’re part of.

A lot of that is competition, but those labels also influence how we treat and interact with our peers.

In a school where the overarching mentality is “the ends justify the means,” a lot of us are always struggling to keep a label or throw one off. If you’ve always been a, say, 3.4-3.6 student whose grades severely dipped in the last year, the label that you previously identified with and the label others identified with you makes you reassess who exactly you are.

And let’s be honest. Even if we don’t always want to think about it, labeling based on race, sexuality, or gender is prevalent at DV, and this changes our interactions and expectations of people as well.

I recognize the pervasiveness of labels — that third grader who wanted an external label to help her figure out what exactly she was and who she could become is still alive in me and countless other people.

There is a comfort in putting yourself and others into a box. However, you should caution yourself from completely defining someone or something based on one label or letting grades and other labels define people.