Everything Everything “Get to Heaven” and back

February 9, 2016

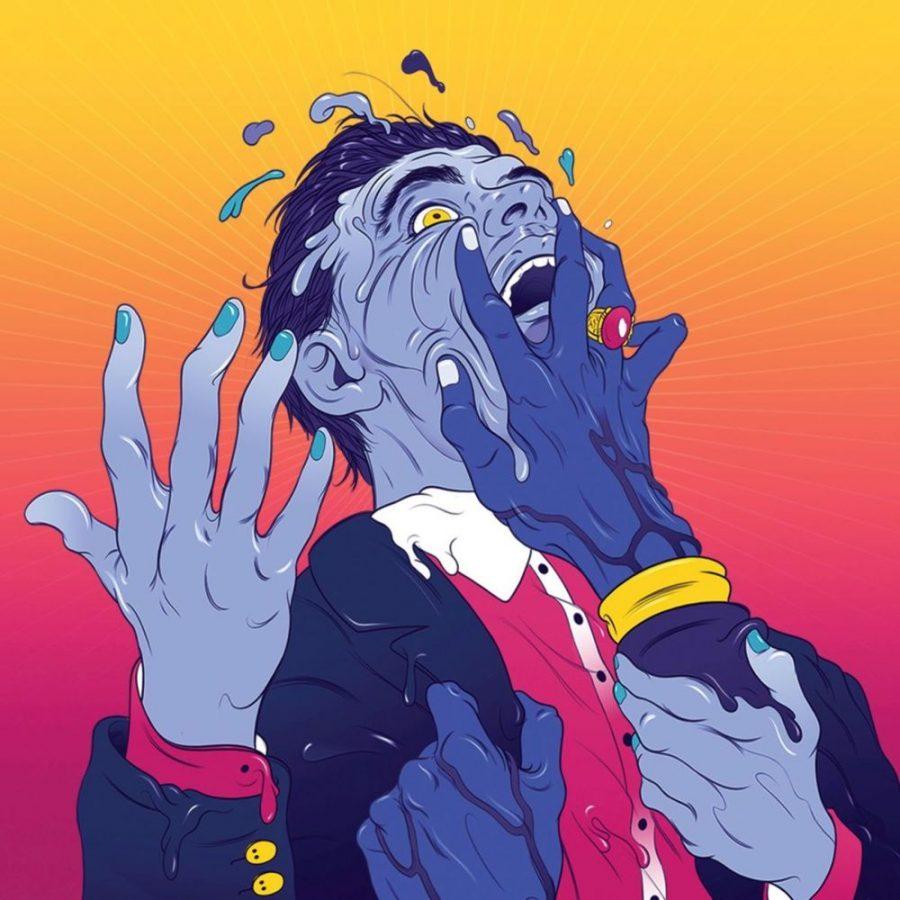

Everything Everything’s third LP “Get to Heaven” stuns as both a progressive, catchy pop album and a powerful dissection of terrorism and war.

Everything Everything are a British pop quartet, formed in 2007, who have been consistently acclaimed but commercially unsuccessful. This has translated to extremely delayed releases in the U.S., where their albums have been released months or even years after their release in the UK. In fact, “Get to Heaven” was released in Britain in June 2015, but is only being released here in the states on Feb. 26.

The album itself is colored by experimental yet accessible instrumentation. Frontman Jonathan Higgs’ and Alex Robertshaw’s guitars are warped and changed into spunky melodies or dark riffs. It’s frequently difficult to discern what’s being played on the guitar or on the myriad synthesizers which Everything Everything employ. Bassist Jeremy Pritchard gets a little more spotlight this time around — while the bass is usually hidden behind layers of melody, closer “Warm Healer” features an extremely catchy and prominent bass line.

But it’s drummer Michael Spearman who elevates Everything Everything to their insanely sticky, memorable heights. The complexity of Everything Everything’s compositions is the highlight, and Spearman’s insane polyrhythms buoy the layered melodies into greatness. The result is one of the most progressive and danceable pop albums in years that never loses its sheen.

Of course, it would be remiss to not mention Jonathan Higgs’ potent and unique vocals. His coos turn to howls in the space of seconds, exemplified on opener “To The Blade.” Soft falsettos yearn for some unknown tragedy, until the track absolutely explodes and Higgs starts howling fiercely. It’s one of many pleasant surprises.

The songs are catchy, often blissful, and have a melodic depth that makes the tracks hard to get sick of. The sound of the album, however, stands in total contrast to the subject matter.

Pop music doesn’t seem like the place to dissect issues like the origins of violence and the endless cycles of terrorism, but Higgs’ excellently written lyrics prove doubters wrong. Every single track fearlessly commentates a unique political stance. Even just on the first half, the LP condenses novels’ worth of psychological and political explorations. The aforementioned “To The Blade” looks at the trauma caused on close friends of terrorists and the shunning they endure once perpetrators are found out; “Distant Past” takes its titular, catchy hook and turns it into a scathing commentary on how history will always repeat itself because of ignorance; title track “Get to Heaven” explores the intersection between mundane problems and extreme violence with the blackest of black humor; “The Wheel” explores the origins of extreme conservatism; the list goes on. But the album’s second half truly astounds, five perfect, consecutive tracks laying bare the humanity behind horror.

“Fortune 500” is the album’s darkest moment, sonically and lyrically, detailing the recruitment of a suicide bomber and his path to “success” with a haunting refrain: “I won, I won, they told me that I’ve won!” It’s one of many to come. But the track’s title reveals a brutal double meaning, one aimed at the (presumably) privileged, Western listener. Higgs uses the Fortune 500 as a metaphor for terrorist organizations until he reverses it and hits close to home. The terrorist organizations become a metaphor for Fortune 500 companies, the backbone of “civilized” modern life. The suicide bomber’s extreme actions for success become a metaphor for the extreme ambition — to excel in school, in college, at a job — of many in the Western world to ultimately satisfy the machinations of some insidious enigma. It’s a gutting reversal, laying bare many of the problems with the ladder-climbing many partake in for ambiguous ends.

“Blast Doors” continues the attack on the ladder-climbing of Western society, again using imagery of bombs and explosives to show the problems with credentialism. “Zero Pharaoh” shifts the focus of the album to the power of power, with Higgs posing hypotheticals about what he would do if he could be the titular pharaoh. With another haunting refrain, he gives in and shows how fear and desire for safety leads to tyranny: “If all your children made it out alive, then why would you ever go back? Give me the gun!”

“No Reptiles” stuns again with Higgs bravely getting into the headspace of a mass shooter. The song lacks any sort of chorus, instead blossoming over the space of five minutes. Subtle, infuriatingly repetitive rhythms burst over five minutes into a heaven of synths while Higgs details the thought process of the mass shooter he embodies. It’s an indescribable experience. Every lyric is a classic, but the shooter’s ultimate justification for his acts is most incredible: “Just give me this one night / just one night! Just give me this one night to feel.”

Closer “Warm Healer” unifies Everything Everything’s vision, with their most abstract lyrics yet. The song brings together the supposedly civilized Western world with the supposedly barbaric third world, detailing an intimacy between a terrorist and a Western figure wherein the terrorist’s actions are left mostly unjudged. Meanwhile, Everything Everything highlight parallel after parallel between our world and theirs, showing that we are not as far from the evil we would like to vilify. “Get to Heaven” ends with a plea and an accusation to everyone: “What’s all that young life been wasted on?” Everything Everything find much more in common between “evil” and “good” than they find different, and the implications of that are unsettling and hopeful all the same.