Writing shouldn’t fit in a box

Over-structuring writing curriculums pushes students towards uncreative and thoughtless work.

April 28, 2023

I hate Algebra.

I detest it, for the very same reasons some people adore it. It is formulaic and horribly unimaginative. You plug numbers into a given formula to get to the single correct answer. Get anything else and you are automatically wrong.

It is for this reason that I have always gravitated towards creative classes, especially English. There are so many different components to a piece of writing, from characters to tone to setting. One piece of art could have numerous interpretations, none of them completely wrong.

As I go through the years of English, however, the two subjects are becoming more and more alike. No longer is English class about exerting your skill in creating a character or a tone. There is no imagination needed anymore to pass an English class, in fact, it seems like the word “creativity” has been sucked out of the curriculum itself. Essays follow strict patterns, and students are given limited creative liberty.

The English curriculum is becoming more like Algebra everyday, and students are the ones who will bear the brunt of it.

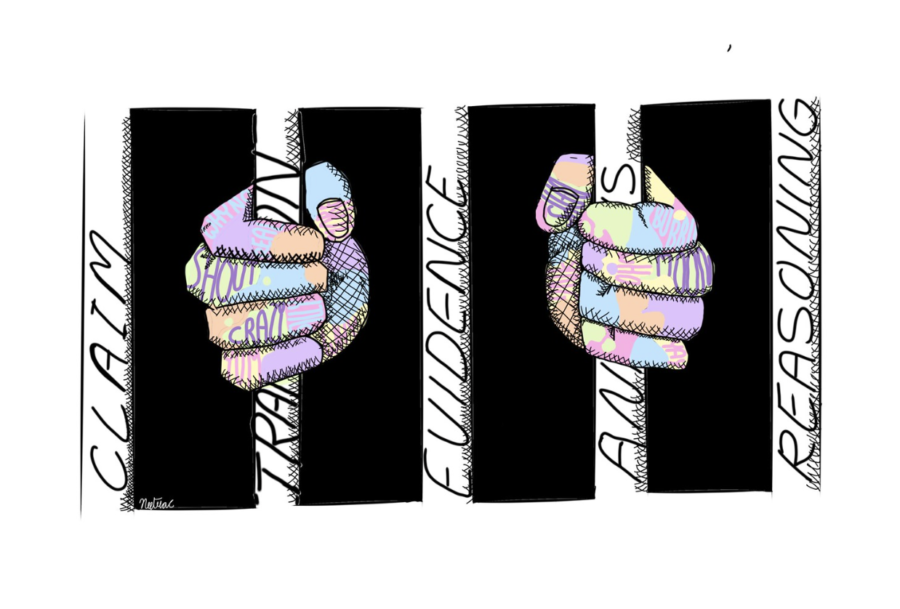

A skill stressed in the current English curriculums is the ability to write an essay using evidence from a text. To students at DVHS, this is more commonly known as the dreaded TIQA TrIQA format. It focuses on developing claim, evidence and reasoning skills. It is most often used in analyzing literary works and acts as the “skeleton” of a strong essay.

As an English 9 teacher, Mr. Jonathan Parks finds this useful to teach his students to help them build a strong base.

“If someone is not being clear or someone is not providing evidence, or someone is not giving that sense of reasoning to their evidence…then TIQA TrIQA is a frame that we use to strengthen those muscles of clarity and reasoning,” he commented.

However, where TIQA TrIQA can serve as a good framework, it can also be a constraining cage. Many educators expect students’ writings to follow the rigid TIQA TrIQA structure sentence by sentence. This leaves minimal room to experiment with wording and structure. The goal of an essay is always to voice some form of opinion. This makes the writer’s individual style and voice crucial to their writing. If each sentence is already planned out in an essay, how is a good writer’s skill supposed to shine?

Instead of laying out a sentence by sentence structure, English teachers should zero in on a student’s complex writing, their formatting and the argument they are making. Does it really matter if the quote is too long or too short, before the analysis or after? Can the student make a good argument? Does the student show an advanced grasp of language? These are the true marks of a good writer and they should be our basis for our standards.

In addition to restricting a student’s writing freedom, the strict structures imposed in English classes may deteriorate specific skills such as vocabulary or the use of figurative language. If students know they can get an A+ by following a specific structure to a T, where is the incentive to write thoughtfully, or in a way that evokes emotion?

Instead, a blank canvas (or in this case, a blank google document) can compel students to experiment with syntax and figurative language instead of mindlessly filling in boxes labeled “analysis,” “evidence” and “transition.”

To some, this rigorous structure is godsend, especially for students less enthused about writing. But why impose the same standards on every student? Writing is an essential skill, and keeping students on these TIQA “training wheels” restricts a student’s growth as a writer.

Even the most basic analysis of “Pride and Prejudice” can be full of new perspectives, artful language and imagery. Even a simple claim, evidence and reasoning can ooze with passion.

So let us learn how to analyze books. Let us learn to be expressive and unique. But most importantly, let us write.