SRVUSD’s changes to English learner programs impact students’ progress

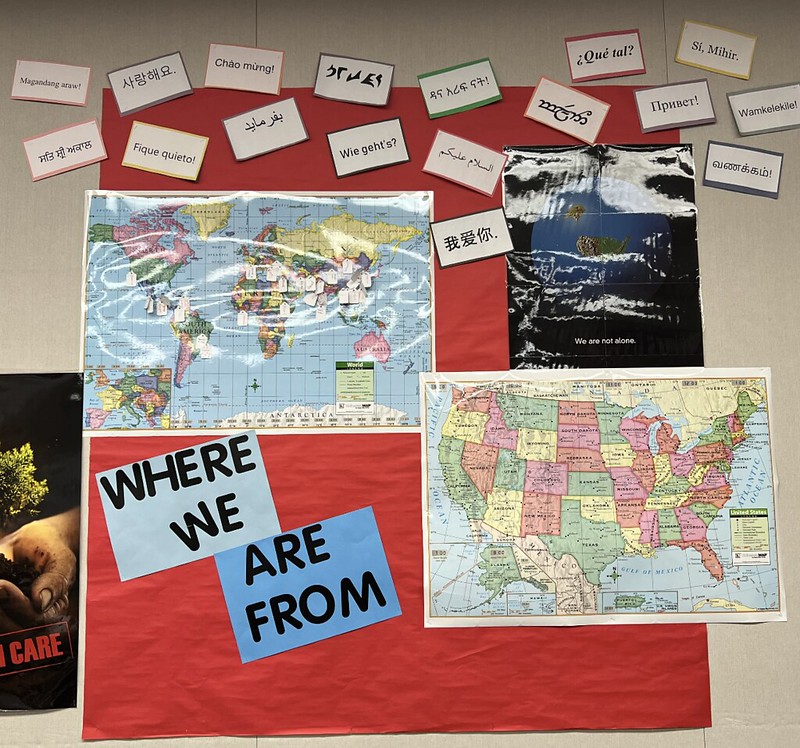

ESL students have found a unique community who celebrate their cultural differences.

April 21, 2023

A new plan to remove sheltered English language acquisition classes at DVHS and integrate students into regular courses is raising the question of how best to support the needs of English learners.

Although the changes are still being finalized, the school intends to remove or reduce the number of sheltered English learning courses, which use the SDAIE (Specially Designed Academic Instruction in English) teaching framework. “Sheltered” refers to classes in which English language instruction is integrated into another subject’s curriculum. Currently, SDAIE courses include language, social studies and science, which would otherwise have a content vocabulary too challenging for students not fluent in English. These students are taught in English, but receive extra academic support to compensate for the language barrier.

The changes come in response to budget cuts and concerns surrounding Title III of the national Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). According to the California Department of Education, this act aims to “ensure English learner students […] meet the same challenging state academic standards that other students are expected to meet.”

During scheduled annual meetings to update the ELD (English Language Development) program, teachers and administrators across SRVUSD voiced concerns that SDAIE classes were too sheltered for English learners to experience the language firsthand, and were therefore not holding them to “challenging state academic standards.”

Assistant Principal Jessica Hoyt, who manages the DVHS ELD program, believes that a lack of exposure to native English speakers could lead to academic and social inequities. She and other administrators questioned whether small SDAIE classes could truly provide immersive learning.

Another worry, Hoyt said, is that “[SDAIE courses] are watered down so that we can support students more with the language. That wouldn’t align with what [state and local] policies are intending to provide, which is rich, equitable, rigorous learning environments for all students.”

Besides the academic consequences, Hoyt added that ELD students and families reported social isolation from the larger DVHS community.

“If we are only clustering [ELD] learners [together], we’re not providing opportunities for them to get a full integrated experience in our school community,” Hoyt said. “If we’re not providing equitable experiences for students, then we are limiting their opportunities, and that is a problem. But also, it’s important that students who are fluent in English have rich experiences, where they’re interacting with students [from] different cultures and with different languages.”

Another incentive to reform the ELD program is its shrinking budget. Until the 2022-23 school year, DVHS received state funding to run ELD classes because it was the only school in the SRVUSD district to offer a full-fledged ELD program, making it a “magnet school.” Students in other schools were offered the option to either remain in their “home school” or transfer to DVHS with paid transportation.

At the beginning of this school year, however, the district determined that because all English teachers in the district are required to have CLAD (Cross-cultural, Language and Artistic Development) certification, they are already qualified to teach bilingual students. Therefore, funding SDAIE classes was no longer necessary.

For the 2022-23 school year, DVHS decided to continue offering SDAIE despite limited funding, in part because ELD students overwhelmingly supported the program. However, SRVUSD has confirmed that they will only fund two of the existing three ELD classes (beginning, intermediate, advanced) for the 2023-24 year.

“The district had to make this decision because we must follow state and federal regulations. The changes […] will ensure that English learners will receive the instruction necessary to support language development while staying enrolled at their home school,” SRVUSD ELD coordinator Deanna Zappia stated.

Beginning next year, DVHS plans to partially integrate ELD students into conventional classes along with the rest of the student body, with additional instruction to help them succeed in their new environment.

“We’re considering a hybrid model,” Hoyt said, “where we still consider how to group and support language learners in sections and courses, but also have them in environments where they are with peers that are fluent in English as well.”

But how exactly the change impacts students’ education is unclear.

The issue, according to SDAIE and ELD teacher Trista McCombs, is that CLAD certification “would not be sufficient” training for teachers. She stated that CLAD merely enables teachers to help students who already have basic English proficiency.

“I’ve been doing this for almost 10 years, and it really takes that long to get to a point where you can help a group of students with multiple languages,” she said. “And to ask to do that [alongside teaching] students who are native English speakers […] I don’t see how the teacher could do it.”

A major hurdle when integrating ELD classes is that students’ individual curriculums must be tailored to match their skills. When a new student enters a California public high school, they take a standardized test, the English Language Proficiency Assessments for California (ELPAC), to determine their language level. SRVUSD students with limited English proficiency are sorted into SDAIE or ELD classes. SDAIE is sheltered and ELD is not, but many students take a combination of both course types depending on their situation. The composition of these classes is also ever-changing, as students from multiple backgrounds enroll throughout the year.

“[ELD student demographics] range from Chinese to Tamil to Dari,” McCombs said. “Sometimes it’s affected by wars in other countries. We got a couple students after Kabul fell. Other students just come in because their families want them to have this amazing education.”

The diversity of backgrounds and skills makes providing personalized instruction challenging. The struggles faced by students must be addressed individually according to their language proficiency, grade level and ability to adapt to a new environment. According to Ms. McCombs, the curriculum is constantly being reworked to ensure that every student gets necessary support. The question is whether the upcoming change effectively solves existing problems.

There is already a significant gap in grades between ELD students and native English speakers. A survey of DVHS ELD students found that nine out of 25 learners received at least one D or F during the first semester of this school year. And with overburdened teachers, the chances of students feeling lost in the classroom are high.

“They are more open to asking the teacher for help, and very rarely do kids not ask for help in ELD because there’s seven kids. [But] in a class of 32, they are not going to ask for help and they are going to be lost, and the teacher won’t even notice,” Yulee Kim, an English teacher at DVHS and former SDAIE learner and teacher, said.

Besides academic difficulties, ELD students risk losing their only community within the school. In order to successfully integrate into a new society, students must go out of their way to pick up English as quickly as possible. Without significant control over their speech, they are unable to communicate basic wants and needs, or even hold a conversation in English with native speakers. These obstacles limit their social interaction and access to resources, meaning ELD classes are a safe haven.

According to McCombs, a main focus of ELD classes is on social and emotional wellness — turning the class into a “family.”

“It really has become a community where we mutually support each other,” she said. “We get to this point where we’re just very happy and comfortable, and they want to come to school. But if I saw some of these same students being forced into a regular class, I could just see them shutting down without the right support.”

How will these issues be addressed? The first step, according to Hoyt, is managing budgets so that as few classes are cut as possible. Meanwhile, strengthening teacher training is a valuable initiative.

“We [teachers] need to be informed because I think that a lot of [us], even if we were trained in from a credential program, many of [us] are far removed from 15 [or] 20 years into teaching,” Kim explained. “We need to be trained.”

Hoyt is confident that with the right training, this change will become an opportunity to improve the school’s ELD resources.

“The concept that we’re providing, having the SDAIE strategies, giving support and training to teachers to help bridge that language barrier, I think we can absolutely provide [that support] in a classroom that also includes students that are fluent in English,” Hoyt said

Until then, teachers and administrators hope to provide ELD students with the best possible experience within the DVHS community..

“We shouldn’t be looking at [it] as a deficit that they don’t speak English fluently,” Hoyt said. “[ELD students] come in with these assets and rich experiences from other cultures and languages, and we want to make sure from a social-emotional standpoint that we’re really celebrating that.”