We need more inclusivity in district language options

Students are forced to choose within a limited selection of languages.

October 11, 2022

As an Indian American (Shreyas), I’ve always tried to keep humble to my Indian roots in a world dominated by American culture. However, unlike my parents who grew up in India, I am a first-generation immigrant to the United States.

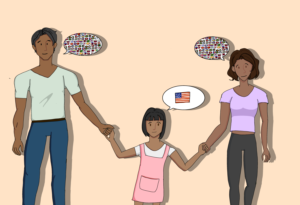

First-generation immigrants feel the heartache that results from losing a first language—I can attest to this. Ever since I was a young child and entered classes with a large English-speaking student body, I, like many of my peers, have lost touch with my mother tongue. As a result, making calls to distant family members became more sporadic and I began to feel a new sense of uneasiness whenever my parents handed me the phone to talk with overseas relatives back in India. While I’m able to still converse in the language pretty well, the lack of frequency in which I spoke Telugu eventually resulted in me losing the beautiful depth I was once able to speak with.

Over time, my mother tongue and the new language begin to coexist as words begin to jumble and my Telugu vocabulary becomes less sophisticated. This is a process known as first language attrition, where bilingual speakers have trouble recalling specific terms or are hindered by a word from the other language. This is especially seen in children who moved from a different language speaking country.

In a predominantly Asian school, many of us speak vastly different languages and come from very different cultures. Most of those languages aren’t offered at school. So the question looming in our minds is why are we limited to just four language options?

Junior Nidhay Mahavadi who takes Telugu at the Manabadi Telugu school said, “I’ve been speaking Telugu since I was born. Even when I learned English as a kid, I was learning Telugu at home at the same time. So I thought, why learn an entirely new language when I can just continue with this?”

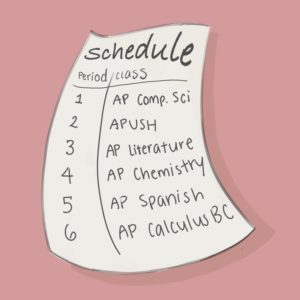

The state of California requires that students take at least two years of foreign language in order to graduate. I hoped that through this I would be able to learn Telugu; however, in SRVUSD the four language options are Spanish, French, Chinese and Korean. This meant that if I were to take a South Asian language like Telugu as my graduation requirement, I would have to do so outside of school. However, the prospect of doing so isn’t as easy as it seems.

For example, the Manabadi school costs anywhere from $300 to $400 per yearly course, and to some families that may be inaccessible. This is simply another reason that public schools should widen the languages offered in their curriculum.

“I had to spend from 9 a.m to 2 p.m every Saturday and sometimes Sunday for it to be equal to a week’s worth of class. You spend almost an hour each day per class [in school], but since my class is once a week, it’s five hours all at once to make up for it,” Mahavadi explains.

Students do have the option to take the language of their choice, but if it isn’t one of the languages offered at school, their only option is to take it at a different district approved institution.

According to the SRVUSD, “Students are able to put up to 40 credits of non-SRVUSD coursework on their high school transcript but are limited to 20 credits per academic year and 20 credits in any given subject area.”

Afterwards, you must transfer credits from your institute to your high school transcript for which SRVUSD has multiple forms to fill out and their own set of rules of how many non-district courses can be placed on your transcript. Ultimately, taking any course outside of school is an excessive hassle.

Most of you are probably thinking: if a majority of students are taking courses at outside institutions, it can’t be relatively that hard. But it’s important to note that a majority of district-approved outside institutions are self-paced and don’t include meeting with your teachers. You can complete one hour worth of work everyday and you are guaranteed to be on track. In contrast to specific approved language institutions such as the Manabadi school and International Tamil Academy, they require attendance online or in-person for these courses which can be equally draining as attending a day of school.

Obviously, it’s not feasible to have every possible language students speak to be available at school. But considering that a majority of students attending DVHS speak other languages, the idea of adding more languages to the class offerings should at least be considered.

My (Shreyas) grandparents are visiting from India and as a result of me conversing with them in Telugu I feel like I’m gaining the lost fluency I used to have. However, it pains me to know that this familiarity with this language is one that is short-lived as it might once again drift away.