Mindsets and Movements: Exploring the endlessly negative perception of rioting

Though the efficacy of riots is unclear, they are a prominent part of many social movements, and should therefore be discussed.

October 23, 2021

The narrative surrounding rioting is fairly consistent: it’s unacceptable, discredits your movement and is never a legitimate tool for change. I didn’t have any issues with this sentiment; being anti-violence is the most intuitive political stance there is.

But one day, those ideas were turned on their head. I was laying on my living room couch watching the newly released Marie Curie biopic, “Radioactive.” The end of the movie reflects on the impact that Curie’s research had on the world, good and bad. I can’t articulate why, but after years of learning about our country’s indefensible past, I only fully started to grasp those horrors after watching a Japanese man look towards the sky, watching in anticipation of his whole world being turned to dust. Hours after watching that movie, his face was imprinted into my mind. The realities about to befall him overwhelmed me and I had a million questions about who thought creating tragedy at that scale was acceptable, how incredible scientific discovery could be warped into a tool of massive destruction. But there was one question in particular that rang through my mind on repeat: how did we let this happen? That day, I understood why people riot.

We generally understand that the government sometimes has to be violent. We agree that it isn’t ideal and should be avoided, but sometimes it’s the only way to make waves. But we don’t extend that understanding to civilians, especially minorities. Instead, we call them barbarians and completely discredit their message.

I’ve been raised to believe that violence is never the answer, and I hold that principle closely. But I also know that riots have created change in the past. That they’ve been the basis for successful social movements, while peaceful protesting often falls on deaf ears.

Even after researching for this article, I’m unsure of my opinion of riots. But however you personally feel, it’s undeniable that the narrative is one-sided. People love to point to moments of civil disobedience and peaceful protest that created remarkable change, the ideal example being the civil rights movement’s sit-ins which protested segregation and demanded a seat at the table. But at the same time, history classes and politicians often sweep movements based on radical ideals under the rug, such as the Stonewall riots of that same time period. So, to find a balanced perspective on rioting, we have to look back and figure out if violence helped or hurt these successful movements. Do the ends justify those means? I suppose that’s a matter of mindset.

The Civil Rights Movement

In 1958, Dockum Drug Store was the backdrop for the civil rights movement’s first sit-in. Black university students sat at Dockum’s counter for weeks, protesting how they were refused service. Filling the stools, they scared away white customers and severely impacted the store’s business, leading to the owner giving in and desegregating the store after just three weeks.

A few years later, these sit-ins became a force around the country. They escalated and attracted more violence, but still found immense success. These protests broke the law, but they certainly weren’t riots, rather civil disobedience. It’s the best example of how sustained protest with a specific goal can be extremely effective.

Of course, with racial tensions as high as they were, there was also significant violence. But, racial uprisings were decidedly less effective than the peaceful protests. AP US History teacher Mr. Jeff Vangene explained that the Black Panthers were, at large, not a violent organization. But by taking advantage of California’s open carry laws (keeping ammunition on hand, but not in the weapon) they created their current violent connotation. The Black Panthers gave breakfast to poor families, facilitated sickle cell testing and organized bus trips to visit incarcerated parents. But he explained that “it gets forgotten about, it’s the violent part you remember”.

Legacy aside, violence (or the perception of it) was not helpful to Black people of the time either. The National Bureau of Economic Research concluded that areas with severe rioting had more dramatic economic gaps between white and Black people, meaning that it only exacerbated existing racial inequities.

So, in the 1960s, peaceful protests and civil disobedience proved themselves to be the best way to combat racial tensions. But what about now?

Noche Diaz is a pro-riot freedom fighter. He explained to Time Magazine that when Black people use peaceful methods of receiving justice, they don’t win. He explained how even when America had a Black president and attorney general, abusive police were still not federally tried. But in 2015, there was an explosive response to those years of injustice, kickstarted by police brutality that killed Freddie Gray, a young, innocent Black man. Baltimore protested, rioted, looted.

Six officers were charged; Gray’s death was ruled as a homicide.

These riots worked—the officers were brought to justice. Diaz explained, “Society was shaken. Lines got drawn.” But what he failed to mention is the people they brought down with them. NPR reported that looters aimed to avoid ruining Black owned businesses, but extended no mercy towards those of other people of color. Korean-American stores were ravaged, which led to decades of racial tension bubbling to the surface.

It’s difficult to foresee how history will regard the Baltimore uprising. They shut down the city, wrecked local businesses and exacerbated racial divides among Black people and Asian-Americans. They also brought the murderers of an innocent 25-year-old man to justice and created discussion about police brutality that changed the face of the Black Lives Matter movement forever.

Stonewall Riots

If the civil rights movement is the perfect example of effective protest, then the Stonewall riots are the perfect example of effective uprising. As author David Carter wrote in his essay “What Made Stonewall Different,” the 1960s were a uniquely trying time for homosexuals. The Cold War reinforced ideals of masculinity, resulting in the stereotypical “feminine gay man” being further villainized. This aligned with the government’s search for a scapegoat, resulting in the Lavender Scare, where thousands of suspected homosexuals were fired from their government jobs. Homophobia wasn’t born from this time period, but it’s when it became thoroughly legislated.

One injustice born from this hysteria was that homosexuals weren’t served at bars because those bar owners would then be liable for an “unlawful gathering.” In protest of this discrimination, a group of gay New Yorkers staged a “sip-in.” By taking on the methods of the civil rights movement’s sit-ins, they spurred transformative media coverage that led to refusing homosexuals service being banned. Another win for peaceful protest.

But, these safe spaces were quickly violated. Despite homosexuals’ right to gather being legalized, these bars’ Mafia ownership was used as a scapegoat for continued police raids. But on June 28, 1969, the Stonewall Inn patrons fought back. As the cops arrested the patrons, word traveled and a crowd from neighboring bars and escaped Stonewall customers started to form. At first, they just watched and teased the police. Their jeering agitated the cops, escalating the situation. After four cops fought a well-known drag queen, the crowd became a mob. A cobblestone was thrown through the bar’s window, coins were hurled at cops and their cars.

The next day, the police came back and so did the crowd. The violence continued for six days. By the end, it was national news. Hearing reports of a win for gay and transgender people was hugely mobilizing, and the event led to the creation of hundreds of activist groups. The community they found encouraged people to come out of the closet and become politically active and it truly kickstarted the gay liberation movement.

Carter argues that this overwhelming force only could have happened via violence, and has a theory for why rioting worked for sexual minorities, but not racial ones: “Just as nonviolence allowed African Americans to overturn the racist image of blacks as violence-prone and achieve a measure of moral superiority, the use of violence by gay men subverted the stereotype of homosexuals as ineffectual and lacking in courage or masculine qualities.”

But Vangene challenges the notion that Stonewall was a solution to the issues of this minority. While he recognized that it was very influential, he posits that “the community is still fighting for a lot of civil rights struggles … so even in those violent instances, what did they really do?”

It’s impossible to say if violence was the only way to mobilize the gay community. There was a near complete lack of organization before Stonewall, so they certainly hadn’t yet exhausted their other options. But the Stonewall riots’ impacts were immediate, wide-reaching and radical. They prove that while in an ideal world, violence is never the answer, but in some situations it can create a successful beginning.

Riot and Revolution

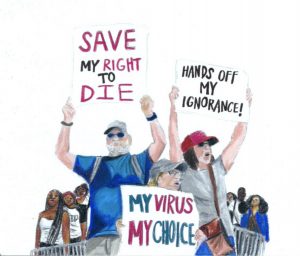

When people are fighting for causes I align with, it’s a lot easier to excuse their methods. But when I watched our capitol be invaded by swarms of right-wing radicals protesting a verifiably fair election, the discussion became much more complicated. The events of Jan. 6 undeniably crossed a line, going from riot to anarchy. But where exactly is that line?

In 1765, Bostonians looted and burned down Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson’s house in protest of the Stamp Act. Despite history classes’ staunch anti-riot stance, this is often framed as a brave protest of unfair laws, a win for Americans everywhere. Vangene explained that it’s important for historians to explore, “how [would] the narrative of that story change if they were rioters, rather than patriots?”

The contrasting opinions surrounding these two riots makes it very difficult to have a definitive stance. The Stamp Act was a clear violation of rights, a cause worthy of immense anger. In contrast, the 2020 election was fair, there was no proven voter fraud. But when it comes to rioting, is there a difference between real and perceived injustice? And if Americans are willing to make excuses for our founding fathers, then who else should get that privilege?

Final Thoughts

I’ve been thinking about this topic for months, discussing it for weeks and writing about it for days. In the end, I’m still not sure how to determine if rioting is a legitimate tool for change. I have no metric or formula that can determine how severe a protest is allowed to be for a given social issue. No way to rule if a group is justified in their anger.

The best I can do is this: no idea, person or movement can be immediately labeled “good” or “bad”. Thus, the way we classify riots as irredeemably destructive removes a lot of nuance and distills a critically important discussion. Only when we open our minds up to this discussion can we begin to understand movements.