Letter grades are fueling the fire of students’ stress

Grades impact one’s mental health, and in a world where it seems that the grades are the one’s who control you, many of us often feel overstressed and loose confidence.

October 11, 2021

Schoology: a new website Dougherty Valley High School has now started using to post grades, and receive homework assignments. But as Bea Elisa Roxas, a Dougherty Valley senior, describes it: “it’s confusing and hard to manage but at least I don’t need to see my grades right away” grades a stigma which have been wrapped around all of us like a lurking pesticide, giving us the highs and the lows. If we receive an A in our AP Biology FRQ our mood suddenly becomes scintillating, exuberant, we raise our shoulders high and walk the hallways in pride as we go to our next class. Because we feel we have succeeded. If we get less than our desired score, our day suddenly becomes a blur as tears clog our eyes and we attempt to put a smile on our face when someone asks how we did. “I did okay.”

We used to hide our grades by clicking “hide progress report” on Schoolloop when someone walked by. We asked others, “How did you do on the test?” Just for them to ask back as you proudly gleam you got an A. It would simply be a fabrication if we state that grades don’t impact us, when the reality is that much of our mental health, physical health, and authentic education are tied into it.

Grades matter. Some may argue that they aren’t important, however, others say that is something which strives kids to work harder.

Agamroop Kaur, a senior at Dougherty Valley, is one of them. “I think grades are important feedback in the learning process but I don’t think they represent holistically one’s learning,” she said.

With that in mind, however, the majority of the kids being interviewed said that grades did not help them but hurt them instead, with the most common words among all interviews being those such as “toxic culture,” “stressful,” “self-deprecating,” “emotional.”

Roshna Junaid Asifali, a junior at Dublin High School, further elaborated. “Grades make me feel dumb and motivate me less to improve because I take tests and realize I am dumb because I never get the score I studied for,” she said.

Many students also stated how grades were their main motivation. Instead of wanting to receive an education, the biggest thing on their mind was what letter grade they were going home with.

An article done by Thnk.org furthered this by emphasizing how grades have become the end goal.

“Grades, ideally intended as an effective means to learn, have transformed into a goal in itself. Grades force students to memorize those details necessary to pass a test, often disregarding true comprehension of the subject matter,” the article explains.

Asifali mentioned this being a huge part of her education, “Whenever I am studying, I don’t do it to learn but I do it so I can get a good grade on a test.”

Many others also feel that letter grades do not accurately reflect students’ knowledge in the class.

Isabelle Sana, a senior at Dougherty Valley, collaborated by saying “I thought I struggled the first semester of my AP Calculus AB class because of the grade which defined how well I was doing. But this year when I was tutoring for my former AP Calculus teacher, teaching algebra … unexpectedly I felt the urge to help students with their Calculus as well. My teacher was surprised that I knew what I was doing and I ended up proving to myself and my teacher I was more knowledgeable in this subject than my grade said I was.

Perhaps the grading system has worked well in the past, but in a life where everything can be Googled and a 0.1 difference in your GPA can keep you from getting into a college, the grading system we have is dangerously outdated.

Karie Chamberlain, a social science teacher at Dougherty Valley, explained how in the past, the grading system worked, and it didn’t matter whether you got a C in English if you were going toward a science major. But now since everything is so heavily weighed into one’s GPA, it has almost become a race to get an “A”.

“[Admissions officers] don’t look at applications that closely anymore, you get eliminated by your GPA. And so it became just this, this battle to get an A, which became a discussion about point values, why did I get a nine or eight out of ten. I felt like the conversation wasn’t about their understanding of the material or where their skill level was, it was just what it is one thing I need to do or two things to get that point I want,” Chamberlain observed

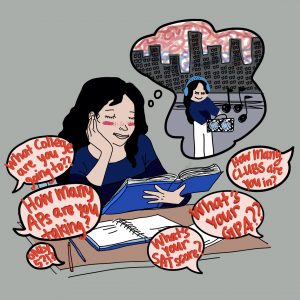

Additionally, many students have begun to feel pressured to take on the rigor of AP classes.

Roxas recalls her experience with taking advanced classes in her sophomore year. “In sophomore year, I took Honors Chemistry and AP World History that completely destroyed me. Everyone around me was [taking those classes], and I thought to myself I should too. I thought to myself how I can fit in any AP, and then like the first few weeks when I was doing badly, I ended up too lazy to drop it. And it made me feel like I was dumb, so I did not drop them.”

This constant pressure of taking rigorous classes and excelling in them often places stress on students’ shoulders leading to fear and anxiety, burnout in the middle of the year, and the feeling of not knowing what you are learning or why you are learning it.

A study done by Education Week reports that “Ditching traditional letter grades reduces stress levels and competition among students, levels the playing field for less advantaged students, and encourages them to explore knowledge and take ownership of their own learning.”

In 2020, when the novel COVID-19 pandemic hit, many schools including Dougherty Valley had transitioned into online learning for the second semester making grades pass or no mark instead of letter grades.

Roxas emphasized that the change in grading had alleviated some of her stress and allowed her to focus on other hobbies, which she would not have been able to do before.

“Because of the pass-fail, I did not need to worry much. I had extra time and I found things I liked to do like crocheting,” she said.

If many students know the implications behind letter grades, and how they may not accurately portray our learning. Then why do we continue to put so much stress on them? Why do we constantly let our grading app control our emotions? The answer may stem from social issues rooted in Dougherty’s culture.

“I think people just want to be better than everyone else,” Roxas recalled. That sounds bad, and we don’t mean to do it, but we’re just conditioned to do it naturally. At school, we’re always asking each other what we got on a test, and we end up doing it out of habit. But then later we realize, they did worse than me. That makes me feel smarter, or they did better than me, so that means I’m dumb. So it’s like we just compare ourselves to each other without even realizing it.”

Some teachers at Dougherty are trying to change that mindset by implementing new grading styles which will help students further their education to the best degree.

Mr. Liddle, an AP World History and World History teacher, started standards-based grading instead of traditional grading.

“Standards-based, or sometimes called evidence-based grading is essentially just a form of grading which focuses more on skills accomplished versus the form where you do a single test on a single day to determine your understanding of a subject, kind of like a breakdown on an assignment,” Liddle explained.

This further emphasizes that in standards-based grading, he looks for whether the student has demonstrated mastery of a concept, rather than have them memorize dates and events. It is based on how well a student demonstrates a skill.

Chamberlain, another social science teacher, follows the same system, and in her classroom, she revealed, “there’s never a day where you’re going to come in, you have a short write and you don’t know what the topic is.”

Like Liddle, she doesn’t do multiple-choice tests in her classroom. “I’ve also had kids who were like, can you please just give me a multiple-choice test? I have perfected the skill of the multiple-choice test. This critical thinking is just not it for me.”

Overall, one of the biggest benefits students may find with this system would be reassessments and extensions. Liddle explains how he has reassessment options because “at the end of the semester your grade should reflect what you can do by that point, and not necessarily where you were in the very beginning. The idea is that if a student really does make improvements, and a student really does like to commit themselves to improve that, then by the end of the semester, their grades should reflect that improvement. That doesn’t mean everyone gets an A, but their grades should reflect that improvement.”

Many argue that this grading system is necessary in order for students to stay motivated and continue working. However, a study by the Aurora Institute argued that reassessments are a necessary part of the school-wide grading policy.

“Reassessment is a part of our real world. I find it ironic, then, that, as educators, we cringe at the thought of allowing reassessments in the classroom in an effort to ‘prepare kids for the real world!’” Rick Wormeli, a teacher at Sanborn Regional High School in Kingston, New Hampshire emphasized.

Adding on, he said “True competence that stands the test of time comes with reiterative learning. We carry forward concepts and skills we encounter repeatedly, and we get better at retrieving them the more we experience them.”

Chamberlain states that as an academic enrichment teacher, she sees that “Once students are struggling, they sometimes mathematically can convince themselves that they can’t get an A or a B, and so they completely write it off. There’s no way I can convince them ‘you need to keep practicing this, even if you’re not going to pass the class, or get the grade that you want; you need to practice a skill, especially if it is something like math, oral language, or science’. So, if there’s a chance for them to redeem themselves, which I think a standards-based grading class does, then the argument is out the window; you can turn that F completely around and pass pretty nicely.”

This standards-based grading system allows for kids to further master their goals as they are allowed to retake tests until they get the desired mastery they would like, and it also lets them continue having confidence in themselves and staying motivated in a class.

Maybe it is the pressure around grades that students put on themselves, deeming their grades to be the only way to measure their intelligence or be socially accepted at this school. Maybe many students find grades a way to keep themselves motivated or something to work towards. Maybe grades actually hinder a student’s education and prevent them from learning, as they are too scared of ‘failure’.

However, we must remember that school is just school, grades are just grades, and they aren’t a representation of who you are.

“Your own path is your own path and wherever you end up is wherever you end up, you will end up flying. Despite what you get on tests, how well you do, as long as you try your best, you’ll be fine, no matter what.” Roxas advised.

In the end, we come back to the question: what even is an A? Is it an accurate measure of a student’s understanding and knowledge of a topic, or is it a measure for how many nights a student has crammed to study for a test, only to forget the knowledge the day after?