Queerbaiting hooks viewers for the wrong reasons

Queerbaiting ensures shows gain fans without losing them and furthers the lack of meaningful LGBTQ+ representation in today’s media.

May 24, 2021

“Cas, not for nothing but the last person that looked at me like that, I got laid” -Dean Winchester to Castiel (Supernatural). This provocative quote is just one of countless examples of queerbaiting in modern media.

Queerbaiting, the practice of teasing LGBTQ+ relationships in order to gain the viewership of queer audiences, is ever-present and hurtful in mainstream media. Through suggestive advertising or intentional acting, queerbaiting ensures shows gain long-term fans while furthering the lack of meaningful LGBTQ+ representation in today’s media.

To understand modern-day queerbaiting, one first must look to its predecessor: queercoding. Queercoding dates back to the 1930s where the Will Hays’ Hollywood Production Code or Hays Code was first created to ensure media had a good influence on the public. It featured a list of rules that American movies had to follow in order to self-censor their content. One of which, depictions of sexual perversion, applied to characters attracted to the same gender.

This ban applied to all characters attracted to the same gender and because of it, creators could not develop characters who were outright queer. Instead they created personalities who retained traits commonly associated with homosexuality without ever confirming their sexuality. Examples of queercoding can be seen throughout history with Joel Ciaro in 1941’s The Maltese Falcon and, more recently, Ursula from The Little Mermaid (1989) and HIM from the Power Puff Girls (1998).

Modern-day queerbaiting

As the 2010s began and civil rights movements and protests continued, creating one-dimensional and stereotypical queer characters became a point of contention with audiences. Networks found that something that was once used as a comedic punchline was now losing them viewers. This is where queerbaiting came in.

Queerbaiting was a way for networks to dance around the now-problematic queercoding and instead tease at future queer relationships without delivering anything real or substantive.

A perfect example of queerbaiting is the crime drama Rizzoli and Isles where promotional materials and specific scenes were deliberately used by the creators in order to hint at a lesbian narrative that did not exist.

An article from Medium.com entitled “Queerbaiting and You. an analysis on an evolution” references a promotional photoshoot done by the two lead actresses on the show where they are posed in what looks like an engagement picture.

“The clear focus on the relationship between Jane and Maura as the core dynamic that made the show work, and the way in which the actresses posed in the photos is in direct opposition to the man-of-the-week C-plot tacked on to every moment of intimacy shared by [the] characters on screen.”

The “man-of-the-week” storyline that is referenced means that each episode the characters have new and not very well thought out male love interests. Consistently introducing random men into the show highlights the idea that though promotional material suggests the womens’ relationship is more than friends, the plot purposefully suggests otherwise.

This same idea can be seen again in promotional material for season 3 episode 5 of the teen drama Riverdale. The teaser trailer for the episode features two men kissing, one of which is out as gay on the show. Fans began to get excited that maybe Riverdale was beginning to try and diversify the relationships on their show. However, upon watching the episode it seems the kiss was used as shock value for one of the characters to violently attack the other. Once again, viewers are misled by the creators of a show.

This leaves fans continuously discouraged as what they hoped would be a queer realtionship turns out to be completely glossed over by showrunners. It feels as though they are constantly being teased of something happening but having it taken away every time.

Not only do fans feel deceived, but sometimes, after being made aware of the overwhelming media buzz surrounding a potential queer relationship, showrunners will ask actors to build up this tension to retain viewers. Whether is be through a lingering gaze, careful editing or smartly crafted dialogue, creators want to create content that keeps fans engaged with the queer relationship but also include obstacles blocking it from ever becoming canon (real in the show).

In a TV Guide interview Angie Harmon (Jane Rizzoli) explained that many times on set they would be told by showrunners to play up the relationship between Rizzoli and Isles in order to keep queer fans engaged.

“‘Sometimes we’ll do a take for that demo,’ Harmon admits. ‘I’ll brush by [Maura’s] blouse or maybe linger for a moment. As long as we’re not being accused of being homophobic, which is not in any way true and completely infuriating, I’m OK with it.’”

Instead of being “infuriated” at being called homphobic, Harmon should understand that this practice of intentionally baiting queer audiences is decieving and aggravating for “that demo”.

Instead of building up the so-called “relationship”, some shows will go as far as to have the actors address the potential relationship and point out how ridiculous or delusional it is.

The BBC mystery drama Sherlock is well-known for doing just this. Since the premiere of the show, fans have obsessed over the chemistry between multiple male actors.

Season 3 episode 1 of the drama features a scene where Sherlock and Moriarty are close to kissing until it is revealed that this is a fanfiction being written by a writer of a Sherlock fan club. This writer promptly gets reprimanded by another member of the club on how ludicrous her story was.

Through this scene, Sherlock blatantly called out the fans of this queer relationship and labeled it as crazy, swiftly crushing the hope of fans everywhere.

Apart from showrunners discounting these relationships, many actors also play a role in this practice.

The CW show Supergirl is also famous for teasing a queer relationship between Supergirl and Lena Luthor with zero follow through.

At comic-con in 2017, while performing a musical recap of the show’s second season, cast member Jeremy Jordan referenced the couple (commonly known as Supecorp) and sang that “THEY’RE ONLY FRIENDS! THEY’RE ONLY FRIENDS! They’re not gonna get together, they’re only friends!”

Jordan promptly apologized on Twitter after receiving a large amount of backlash from Supercorp fans. However, the fact still remains that he discounted the validity of what fans of his show were seeing.

Showrunners intentionally build up tension between characters on screen but then actors and creators poke fun at fans for hoping that their beloved queer relationship will actually exist. This altogether is not only a lazy way to gain fans but a form of gaslighting hopeful viewers through the continuous invalidation of their feelings.

“It’s sort of like the bully that takes someone’s hand and says ‘stop hitting yourself stop hitting yourself’. They are teasing the people who are supporting them by saying ‘hey we know what we’re doing and we’re going to keep doing it.’” Kopp explains.

This makes excited fans feel laughed at and disillusioned because they are being fed two different narratives. And queer fans lose hope in ever seeing themselves represented on screen in a meaningful way.

Why do people fall for it?

A large reason queer fans even latch on to these small intentional marketing ploys is because there is a lack of accurate queer representation in mainstream media for them to see themselves in.

What makes the practice of queerbaiting even worse is that showrunners know this. They know fans are starved for meaningful representation and creators capitalize on that need. If they even tease at a queer relationship, fans will tune in hoping to finally see themselves reflected on screen.

What exacerbates this issue is the rise of social media. Specifically platforms like Tumblr. Launched in 2007, Tumblr was created as a short-form blog website but has turned into a hub for obsessive fanfare. Nowadays it is well-known as a safe haven for queer fans wanting to meet others who share their interest of specific tv couples.

A 2019 study published in the International Journal of Communication found that of individuals aged 16-35 who identified as a part of the LGBTQ+ community, 65% said they use Tumblr. The main reason for this: “Tumblr brings together people with shared interests from unconventional ‘subcultures.’”

Among these “subcultures” are fans of numerous queer couples with the collective wish that their ship (pairing) will become canon. Through endless posts and reblogs, viewers will pick apart pieces of every new episode of a show to find details that affirm their belief that this pairing is true.

After every episode of Sherlock, thousands of fans would make edit after edit of a specific scene where John stared longingly at Sherlock or when a suggestive comment was made by another character.

While this was satisfying fans’ needs to see themselves in these characters, it was also doing the creators of these shows a great benefit. The more people talked about the show, in whatever capacity, the more press and buzz their show was receiving and the more popular it became.

Soon showrunners realized that by creating even more tense moments between characters or provocative dialogue to pander towards these fans, their popularity would continue to increase. By taking advantage of eager fans who just want to see themselves represented in mainstream media, creators and showrunners made the problem of queerbaiting even worse.

But this eagerness of fans can also cause a little bit of a grey area for queerbaiting. Tumblr is also notorious for putting characters together that do not have any relation to each other or projecting a certain sexuality on characters without any confirmation.

These practices make many say that queerbaiting as a practice does not exist because it is the eagerness of these fans that makes them read into relationships where there is nothing to read into. ‘If people on Tumblr are pairing Harry Potter and Draco Malfoy together then its not queerbaiting, it’s just fans being hyperintense.’

However, one clear idea creates the distinction between mere fan theory and queerbaiting: creator’s intent.

Fan theory is a much broader term. Since the release of Force Awakens, theories and edits have been circulating about Luke Skywalker from Star Wars. Fans have been finding small details like the fact that he never kissed any woman in the series except for his sister to be indicators that Luke was gay.

When asked about it, Mark Hamill (Luke Skywalker) said that “Now fans are writing and asking all these questions, ‘I’m bullied in school… I’m afraid to come out’. They say to me, ‘Could Luke be gay?’ I’d say it is meant to be interpreted by the viewer…. If you think Luke is gay, of course he is. You should not be ashamed of it. Judge Luke by his character, not by who he loves.”

This instance is an example of fan theory being supported by the actors of the medium. The intent here is not to capitlize on queer audiences and fabricate queer moments to gain viewers but instead to validate the feelings of fans and their interpretation of the art that was created.

On the other hand, some creators directly contradict this situation. In the example of Rizzoli and Isles that was previously discussed it can be seen that these actresses were specifically told to act in a way that suggested a queer relationship. They were only told to do so because creators wanted to ensure that queer viewers remained engaged. Here, the intent is not to let fans interpret art, it is to purposefully create a narrative that fans will eat up and indirectly increase the popularity of a show.

Another example where the difference in intent is shown clearly is in the advertisement for the live-action Beauty and the Beast. Bill Condon, the director of the film, revealed in an interview that Gaston’s sidekick, LeFou, would explore his sexuality in a “small but significant subplot”. This revelation excited queer viewers as this would be the first openly gay Disney character.

However, USA Today says that “the “gay moment” that Condon was referring to is a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it shot in the film’s final seconds. LeFou, the villain Gaston’s (Luke Evans) side-kick, dances with a man in the final ball sequence just before the credits roll.”

In the context of the movie, this single moment was definitely not a “significant subplot” as suggested by Condon. Instead, is is yet another example of creators capitalizing on the excitement of queer viewers and letting them down every time. Once again, the intent was to get viewers, not to be inclusive.

The idea of intent makes the practice of queerbaiting all the more aggravating because, to put it plainly, creators have no intent to actually display queer relationships. They are instead using a demographic that has been marginalized for years in media to gain viewership and profit.

“They [get] the benefit of pulling in queer viewers, without actual representation that would affirm who those viewers were and make the world better for them” Kopp says.

So… now what?

At the end of the day, the idea of queerbaiting is very cyclical. Queer fans do not see themselves represented meaningfully on screen so they turn to turn to shows where they can find small elements of a relationship and create their own narrative to make themselves feel more seen. But showrunners are deliberately creating these small elements to increase profits and with zero intention of ever including an actual healthy queer relationship. And so, queer relationships are further misrepresented in media.

This ever-prevalent practice will not go away until showrunners understand that what they are doing goes beyond an increase in viewership.

“It’s not just ‘I look up there and I see myself and I’m good’,” says Kopp. “The bigger thing for young queer people, especially people who are just coming to terms with their sexual orientation, is other people are watching this, and they’re liking it, and they keep coming back to it. And so that means that when I grow up, there might be a world out there where people who are straight or cisgender, have some point of reference for where I’m coming from, and are going to support me.”

According to Kopp, the only way that creators can accomplish this goal of fostering empathy whilst affirming the identities of queer youth is to have “queer and trans characters woven in with straight and cisgender characters and having their own storylines that are important”.

But while showrunners and media producers grapple with understanding their responsibility towards queer audiences, fans must have the knowledge and courage to call out queerbaiting and make the choice to not consume fabricated queer content.

Understanding how to recognize queerbaiting whether it be through advertisement, actor portrayals or cleverly edited footage is the first step to stopping the practice of queerbaiting in shows. Viewers should ask themselves “Is this created to better represent me or to capitalize on my excitement?”, “Is this advertisement edited in a specific way to pique my interest?” Fans should understand that good queer representation comes from healthy relationships being weaved in with straight and heterosexual stories. And that having one queer character in one episode of one season is not what the LGBTQ+ community needs or deserves.

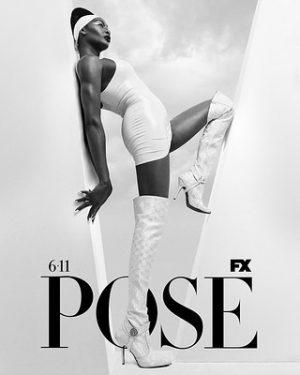

Shows that already practice healthy queer representation such as Sex Education, POSE, Schitt’s Creek, One Day at a Time, Dear White People, Star Trek: Discovery, Bojack Horseman and many more are ones that should be consumed by fans.

In promoting shows like these and becoming more knowledgeable about the practice of queerbaiting, fans will ensure perpetrators of queerbaiting do not gain the viewership they want and instead see a decline in popularity.

“The queer community has a certain agency to to boycott programs… and say we’re going to vote with our clicks, we’re going to vote with our views, we’re going to vote with our dollars.” Kopp says.

In our increasingly technological world, views matter and where we choose to use them can be the difference between someone feeling safe in who they are and feeling targeted. If shows don’t want to challenge the views of queerphobic viewers, then fans have every right to challenge creators for their lack of action.

Views lead to profits, so once shows realize that their practice of queerbaiting is actually losing them fans, they might dain to introduce healthy queer relationships into tv worlds.

Until showrunners realize the harm they’ve inflicted on a generation of queer fans, Kopp explains that the only way for authentic queer content to exist is if more people begin to create it. All queer experiences are different and the only way to reach as many viewers as possible is if anyone who wants to, creates content that they wish to have seen.

Showtime’s “The L Word” was the first show with an ensemble cast depicting lesbian, transgender and bisexual characters. Alexandra Kondrake, writer and producer for the show, explained to Lafayette Student News that “It was I just writing about my life… But writing about my own life can be really powerful and entertaining for other people.”

Just as Kondrake drew on personal life to create a show that pushed the boundaries of queer representation, director Dee Rees utilized her own story to pave the way for other queer movies in her semi-autobiographical film, Pariah.

The movie, which Rees began writing after coming out to her parents, premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2011.

Of the premiere Rees told Indiewire, “I just remember people coming up to us being in tears, being moved, saying that we told their story… I definitely feel like it was a turning point for Black cinema generally, and Black queer cinema specifically. It was telling a story from a vantage point that hadn’t necessarily been seen.”

This is the strength and progress that comes when queer viewers take their frustrations with the TV and film industry and turn them into art. If something is not seen or represented accurately on TV then anyone who is willing can help change it. Everyone has a “vanatge point that [hasn’t] necessarily been seen” and putting that into the world can ensure that other queer viewers feel safe knowing their experiences are valid. It can mean the difference between viewers feeling alone or truly seen. And it can ensure the queer community is not taken advantage of but celebrated instead. Kopp puts it simply:

“If you want the world of queer representation to be better. Go write it. Go make it.”