NPS threatens endangered tule elk at Point Reyes National Seashore: an exploration of sides and solutions

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

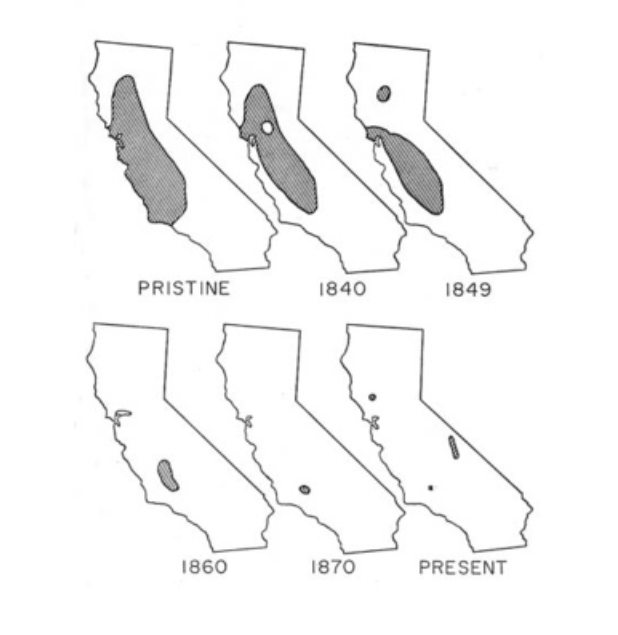

Tule Elk Population Distribution Maps of California, Past to Present

October 24, 2020

In the 1870s, there were ten tule elk left in the world.

These 10 individuals were leftovers, the ghosts of a species that had been hunted to near extinction by Europeans. Endemic to California, the last tule elk— the smallest subspecies of American elk— wandered on the cusp of society for years, grasping on to survival in the grasslands and marshlands. It took a century of steadfast conservation efforts to bring the tule elk population back to 4,000 individuals.

The tale of the tule elk was a rare conservation success— and one that only lasted 50 years. On Sept. 18, 2020, the National Park Service (NPS) proposed a new management plan for Point Reyes National Seashore, one that would expand cattle ranching within the park’s borders and allow for the controlled culling of endangered tule elk.

Point Reyes National Seashore is described on its website as “A Natural Sanctuary, A Human Haven.” Now, it may become a human haven, and a cattle sanctuary.

TWO WORLDS, TWO SIDES

This is a land where two worlds collide. The ocean and the earth are stitched together by a winding coastline, jagged with tawny cliffs and tumbles of white water. Further inland, a veritable paradise of biodiversity thrives in the salted air: coastal prairies full of bunchgrasses, forests of fir and pine, salt marshes and coastal dunes— all of it jumbled into one park.

“I vividly remember being surprised by a gray whale while sitting at a favorite spot once,” recalled Matthew Polvorosa Kline, a wildlife photographer who has documented Point Reyes for years. “A loud blast of air, the whale’s breath, shot out from its blowhole when it came to the surface not at all far from me.”

Move away from the coast and the wonders don’t cease— if anything, they multiply. Half of all bird species found in North America have been spotted within Point Reyes. 194 species of mammals, fish, reptiles and amphibians wander this coastal wonderland. Traverse the shoreline, and you’ll find crustaceans, mollusks and other invertebrates battered by the sea.

“A peregrine falcon once landed so close to me on a cliff edge, I actually had to back up slowly from her to be able to take a photograph,” says Polvorosa Kline. “She calmly preened her feathers for a number of minutes and was perfectly fine with me so close. I once had a bobcat hunt for gophers and voles just a few feet from me as I was lying on the ground taking photographs.”

Point Reyes isn’t just home to such tremendous biodiversity; it’s a refuge. Over 100 plant and animal species found here are classified as threatened, rare, or endangered. Trace the west coast along a map and you’ll find 7,623 miles of Pacific coast— and in this entire stretch, Point Reyes is the only area dedicated as a National Seashore.

Perhaps it bears repeating: Point Reyes is a national seashore. It’s an area of land set aside to be protected by the government as a public, natural preserve. In a world increasingly consumed by human activity, national parks are the last wild places that the public can take for granted.

Current estimates place the tule elk population at 5,000 to 7,000 individuals remaining, still only a fraction of the original 500,000 in the pre-settler era.

Of this, around 750 elk live within Point Reyes National Seashore. It is the only national park in the United States where visitors can enjoy tule elk; likewise it is the only place where tule elk can roam unthreatened— supposedly.

It’s a complicated matter. And as usual, it gets more complicated. It’s easy to get lost in the tangle of legal compromises and adamant accusations of both sides. But it seems to me that there is one shining principle that cuts through it all. To advocate the culling of an endangered species isn’t just contrary to everything the National Park Service stands for; it’s contrary to what humans, as part of a vanishing world, should be ultimately working towards.

A BATTLE ACROSS BARBED WIRE

As of now, ⅓ of the entire park (28,000 acres) is already dedicated to ranching operations. Early settlers, after nearly extirpating the tule elk, established these ranches— now regarded as “historic” by many residents and visitors. Rightly so, it could be argued: the very people who helped found the park were ranchers themselves, and their ranches still serve as legacies.

The historic value of the original cattle ranches is a central argument for those who support NPS’s new plan. Yet the number of operating ranches is questionable at best, and their cultural value is inflated.

“There are thousands of ranches around the country that are more historic than these, including the one in the Tule Elk Reserve— Pierce Point Ranch— which is no longer active, but provides visitors with historical insights,” said Polvorosa Kline. “How many of these do we need in such a National Park?”

In proposing their new management plan, NPS assessed six options for ranching within the park’s boundaries. They strode a fine line— a jagged line which divided environmentalists and ranchers, tule elk and cattle, facing off tensely on either side.

On Sept. 18, NPS announced that they would implement their preferred option: Alternative B. Alternative B would favor the expansion of cattle ranching at the expense of native wildlife.

Specifically, it would extend ranching permits in Point Reyes from five years to up to 20 years. 7,600 acres of land would be added to the Ranchland zone (2,350 acres of these lie within Point Reyes), allowing for an expansion of industrial operations. And the Drakes Herd population of tule elk would be limited to 120 individuals— thus allowing ranchers and park management to shoot and kill tule elk.

“The last thing that we should be doing anywhere in this state, anywhere in our country really, is targeting and killing severely diminished native species and promoting the most invasive and destructive one of them all– cattle,” said Polvorosa Kline.

This is a statement widely backed by environmental organizations, such as Western Watersheds Project, Resource Renewal Institute, For Elk, Conservation Congress, Wilderness Watch, Sequoia ForestKeeper, Shame of Point Reyes, TreeSpirit Project, John Muir Project, and Ban Single Use Plastics.

The tule elk and the cattle. Imagine them, if you will, on opposite sides of a fence. Zoom out a little, watch as the land spills out beneath you. The tule elk wander over a lush coastal prairie bordered by dark smudges of forest; the cattle amble through barren, gray-yellow fields nibbled to the root.

And in between them, the fence.

It is the only thing that separates the dedicated ranchland from the rest of the habitat. But a fence of barbed wire isn’t enough to prevent the consequences of cattle ranching from spilling over into protected land.

Cattle have devastating consequences on the environment— it is undeniable. Their hooves carry and spread the seeds of invasive plants. Overgrazing and manure-spreading erode soils. They contaminate water sources and spread bovine diseases (such as Johne’s disease) to vulnerable elk. The cattle, wildlife biologist Laura Cunningham told National Geographic, “treat native bunch grasses as ice cream cones and eat them down to the ground.”

While Alternative B has the support of NPS, a commenting period on the draft drew 7,600 comments from the public. An overwhelming 91% were against Alternative B and the expansion of ranching.

The solution seems frustratingly easy: drop Alternative B and adopt Alternative F, which would discontinue ranching operations and open up the land for tule elk and visitor use. This would benefit all wildlife in the park, stifling negative impacts on soils, water resources and vegetation.

But it is not that easy. There are, after all, two sides of the fence.

TOO MANY TULE ELK?

The tule elk of Point Reyes must be managed to maintain a healthy ecosystem, some ecologists and park officials argue.

“There [are] no longer predators to keep the elk population in check,” said Kristin Denryter, coordinator of the Elk and Pronghorn program for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. “Historically, [there would have been] wolves, grizzly bears, mountain lions. Now, we really only have mountain lions.”

The lack of predators has contributed to an “extremely high” density of elk in Point Reyes, according to Denryter. “When you have high densities of animals, you get overgrazing, which can denude the vegetation. Animals that overgraze their landscape will run out of food, and then they can have a long drawn out process of starvation, because… there’s nothing left to eat.”

Yet it is hard to understand why overgrazing by cattle (which is arguably much more damaging) is acceptable, and overgrazing by elk is not.

It is also worth noting that wolves and grizzly bears were extirpated by early ranchers, who targeted predators for preying on their livestock. The park has considered reintroduction of predators but discarded the plan, claiming that the bears wouldn’t prey sufficiently on elk and that gray wolves are nonnative.

However, according to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, gray wolves are native to California and were extirpated from the ecosystem in the 1920s. Grizzlies have been well-documented for preying on elk calves. A more likely explanation would be the logistical challenges and costs for reintroduction, rendering NPS’s excuses flimsy.

Options other than culling have been considered, including translocating the tule elk to other regions. But these plans have been dismissed because the herds of Point Reyes are likely infected with Johne’s disease, originally transmitted from cattle.

“There’s nowhere that they can just go to establish new herds,” said Denryter, referencing nearby habitats that are fragmented by highways. “They’re just kind of squished into this small geographic area.”

For NPS, this means that controlled culling of the two free-ranging herds— Drakes and Limantour— is necessary. Their view is that the elk are doing too well within this space.

For Polvorosa Kline, the opposite is true. Having documented Point Reyes with his camera for years, Polvorosa Kline has observed the elk as they struggle to find resources.

Of the 15 elk he has encountered, two were “stuck deep in mud” where they had been searching for water. Another was a big bull elk, dead, his antlers “caught up in old fencing material.” His body was located adjacent to another 8-foot high fence, preventing the elk from foraging outside of the reserve.

Droughts in California, exacerbated by climate change, have worsened situations. In the 2013 to 2015 drought, 250 tule elk died from malnutrition and thirst. With the smoke-charged air, relentless wildfires, and persistent lack of rain that plague California today, it isn’t hard to imagine that the tule elk are going through a similar, if not worse, struggle.

Denryter and others might place the blame on tule elk for overgrazing the land. But, fenced into designated enclosures by the presence of cattle ranches, the tule elk of Point Reyes are limited in their own sanctuary.

“You consider the pressure that [the elk] are under in Point Reyes, and you feel miserable about it,” said Polvorosa Kline. “Because if they cannot be protected and restored in Point Reyes to a healthy and viable population, then where will they be safe?”

The tule elk are dying, and NPS is no longer on their side. The rest is just fluff.

PRIORITIES AND PROFITS

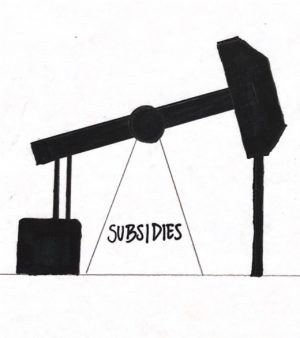

“I’m actually proud of you on this,” said Congressman Garret Graves to Congressman Jared Huffman. “It’s allowing national parks to be managed in a way that’s complementary to commercial activities. It relocates species when they potentially conflict with commercial operations… I’m proud of you, Mr. Huffman.”

This was in 2018, when Congressman Huffman, a supposed environmental leader in the government, introduced a new bill: H.R. 6687. H.R. 6687 advocated for the continuation of cattle ranching within Point Reyes. If native wildlife infringed on those commercial operations, they would be relocated.

Fluffed up with pretentious words, the bill comes off as decent. Strip away the flesh and dig to the bone of the matter, and it seems maddeningly absurd. Cattle ranching on private land? Tolerable. Cattle ranching within national parks? Incomprehensible.

Graves, who resembles The Once-ler from The Lorax when he hacked down the last truffula tree, then joked about the tule elk: “Can you make sausage out of ‘em?”

Yet not every rancher is a villain. There are those in Point Reyes who genuinely seem to care about coexistence, advocating a practice called holistic management.

They take precautions to lower their environmental impacts, preventing cattle from grazing on steep slopes and fencing them out of waterways to reduce erosion and pollution. They implement “rotational grazing,” in which the cattle graze on different patches to give the land time to recover.

“It really challenges us, the ranchers— and I’m not saying all of us are happy about this— to raise the bar and be better,” rancher Dave Evans told National Geographic.

Other ranchers complain about tule elk “trespassing” onto their land, injuring cattle at times, and eating cattle feed. These “excess” elk disturb ranching operations and must be removed, they say. So far, NPS has been complying with their demands.

Is it truly possible for cattle ranchers and tule elk to coexist? The simple answer is: yes.

Ranchers have vast potential to become stewards of the land, harnessing their rangelands for conservation purposes. In 2015, Bay Nature reported on the Yolo Ranch and Cattle Company, run by the Stones family. The Stones utilize their rangeland for good: they help biologists monitor waterfowl activity on their land; they participate in scientific trials on rangeland carbon sequestration; they use recycled water from a Campbell soup cannery to irrigate their fields.

Another rancher-steward is Doniga Markegard, of Markegard Family Grass-Fed near the Santa Cruz Mountains. She and her family implement keyline design, catchment ponds, permaculture, and holistic management.

“We try to manage our cattle herd to simulate the large herds of elk and antelope that once roamed California’s grasslands,” she told Bay Nature.

Does Alternative B support coexistence, or does it favor commercial operations over wildlife? Is it a solution or an excuse? Is cattle ranching good, or bad, or both?

“We must recognize that the ‘local’ decisions regarding this public park are not limited to isolated reactions and consequences,” said Polvorosa Kline. “[They] have the potential for tremendous impacts on a larger, more interconnected global scale.”

And he is right. In the Amazon Rainforest, incomprehensible swaths of trees are demolished or burned for cattle clearings. In Africa, cattle ranchers and native predators— such as lions and painted wolves— are slowly learning a tentative coexistence. Ranchers in Chile have called for the culling of the native guanaco, a llama-like animal, for encroaching on pastureland.

Point Reyes— this little snag of land off the California coast— is a microcosm. Not just of the various places where wildlife and ranching intersect, but of the entire planet. Everywhere we look, human beings are fumbling and figuring out their way around a slipping environment.

If we cannot prioritize endangered wildlife in a national seashore, then what hope do we have against environmental disasters elsewhere? There is more at stake than a few cattle ranches; the actions executed in Point Reyes could serve as blueprints for other natural sanctuaries in the future.

“I don’t want to imagine a world without the tule elk,” said Polvorosa Kline. “Simply put, we should fight like hell to protect every last species we can.”