The anti-lockdown movement is an example of the (white) right to protest

The anti-lockdown protests that sparked across the nation favor the “white” right to protest.

May 28, 2020

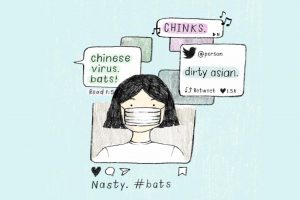

The First Amendment states: “Congress shall make no law abridging the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.” Recent anti-lockdown protests are taking place nationwide as people grow increasingly anxious about the state of the economy and their jobs during the pandemic. However, we forget that the right to protest has not always been so freely granted in America.

The rise of anti-lockdown protests across the United States is another example of how the right to protest is favored in the hands of a specific demographic — those who are white.

As the unemployment rate rises over 36 million, many are wondering whether strict lockdown measures that shut down daily life are worth it— or if they’re all just an overreaction. As President Trump stated himself, “The cure cannot be worse than the disease.” Many anti-lockdown protestors believe that shutting down local, state, and the national economy has done enough damage and it is time to open back up.

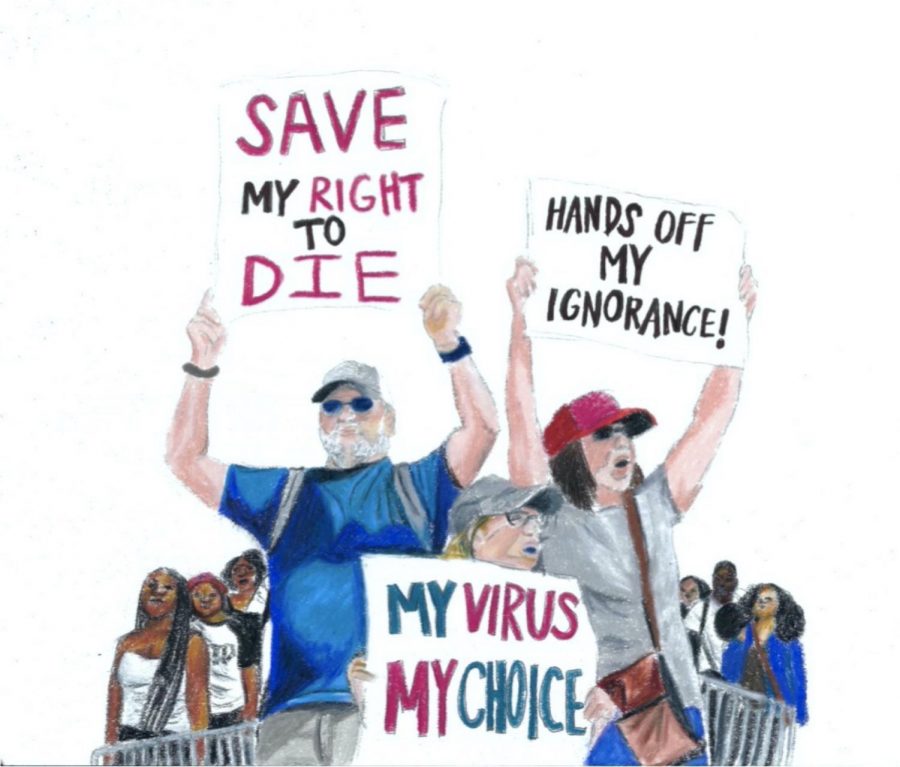

The protests have inevitably stirred up controversy. Many protestors are photographed without face masks while ignoring social distancing measures, primarily because they do not believe it is necessary. An article by USA Today details protestors carrying a “Fire Fauci!” sign in Texas, expressing their frustration with the Trump administration’s infectious disease expert and his reports during this pandemic.

Another key reason for opposition is that not everyone perceives the protests as “friendly.” According to the Atlantic, a group of men stormed the Michigan state capitol last month with assault rifles and demanded lawmakers to lift the lockdown. No one was arrested. In North Carolina, protests showed up at a Subway with guns and a rocket launcher. Again, no one was arrested.

So if no arrests occurred during those two events, why is it that more than 100 protestors were arrested in a peaceful demonstration against law enforcement in New York while anti-lockdown protestors were able to march into the Michigan capitol with AK-47s? It goes back to white privilege. That New York protest was a 2016 Black Lives Matter protest in Rochester that was organized in response to the shooting of Alton Sterling by police in Louisiana.

Started in 2013, Black Lives Matter, a movement with majority African-American supporters, was founded in order to create a world free of “anti-blackness” in response to racism and state sanctioned violence. And although Black Lives Matter has garnered millions of supporters, police in the United States do not always feel the same sentiment. Looking at protests such as the one in Rochester, it’s easy to see that resistance from police in recent coronavirus protests pale in comparison.

Going back to the anti-lockdown movement, a majority of anti-lockdown protestors are white and support the Trump administration. It is no coincidence that groups such as Women for America, a Republican, pro-Trump organization, have been in charge of running a handful of these protests; the sentiments at the heart of these protests overlap greatly with many of Trump’s (initial) efforts to keep the economy open for as long as possible.

It is clear that race was the reason why the New York protest resulted in 100 arrests and why the other, much more aggressive, anti-lockdown protests were allowed to continue with no opposition.

The false perception of many is that the black race is dangerous. Minneapolis Police Union President Bob Kroll called Black Lives Matter a “terrorist organization” and compared protests against police killings “the local version of Benghazi” (referring to a terrorist attack against American government facilities in Libya).

The racist undertones are also present in legislation. In April of 2017, Minnesota legislators proposed the bill HF 390 that vaguely described protest disruptions to public transit fair grounds for arrest, which according to the ACLU of Minnesota, was a direct response to recent Black Lives Matter protests and would create a “chilling effect on speech” as well as “create punishments that are disproportionate to the offense.” Although the bill was not put into law, the bill was still able to gain significant support in the Senate and House, representing an attempt to shut out minority voices.

Whether we realize it or not, the impact of unfair treatment is the prioritization of one social movement over the other. Although the government is not advocating for anti-lockdown protests, by allowing them the right to assemble while suppressing non-white movements throughout history, they are indirectly picking a side, one that prefers whites over all. These actions are what define institutional racism and a violation of constitutional rights.

There are ways to combat the unfair right to protest. One way that minorities can be assisted can include writing letters to Congressional representatives so discriminatory bills such as bill HF 390 that aim to suppress specific protests are not passed. Similarly, movements such as Black Lives Matter or The People’s Alliance for Justice should be further acknowledged in the media to help counter the unequal suppression of their physical protests.

Racism and white privilege will not disappear by the snap of a finger. However, the first step to change is awareness. Though it is important to recognize the individual movements behind these protests, we also need to compare these protests side-by-side to evaluate the fairness of how protestors are treated. As for police, it is necessary to provide equal opportunities, as well as punishments, for protestors to voice their opinions no matter what their racial background is. As an article from the Independent puts it, “It is not whether police should be detaining protestors that has become a cause of debate; it’s that there is a glaring difference that marks the occasions when they decide to do that. It’s as stark as black and white.”

“Congress shall make no law abridging the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.” It is our responsibility to protect the very right guaranteed to all American citizens in the First Amendment. It means nothing to have a voice when the white one is the only one heard.