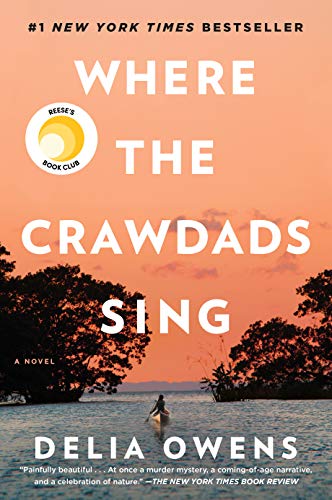

Delia Owens paints a marshland mystery in her fiction debut “Where the Crawdads Sing”

“Where the Crawdads Sing” is a bewitching tale of murder mystery and nature.

December 1, 2019

Venturing into fiction for the first time, acclaimed zoologist Delia Owens carves a bewitching tale of isolation and the ancient thread between humanity and wildlife. It is dreamy and nightmarish and tangible all at once — until the final scenes.

Released August 2018, “Where the Crawdads Sing” blends murder mystery with a heartfelt celebration of nature, grounded in a coming-of-age narrative. The wildly popular novel was the September pick for Reese Witherspoon’s book club, spending 44 weeks on the New York Times Bestseller List. It follows the story of Kya, a “wild” outcast, as she navigates to adulthood on paths mimicking the convoluted marsh waterways in which she wanders.

It is 1952, and the North Carolinian town of Barkley Cove is laced with Southern mannerisms and rampant segregation; the marsh, for Kya, is a refuge. At 10 years old, she slips into isolation as her mother, her siblings and eventually her father desert her one by one. Forced to survive on the fringes of society, Kya gradually drifts into a primal existence tethered wholly and beautifully to the marshland.

The novel unfolds in two pieces: one following Kya’s evolution from 1952, the other rooted in 1969, the year a man is found dead in the marsh.

In a simple, sizzling style reminiscent of Barbara Kingsolver, Owens’ voice is visceral yet subtly profound.

“Marsh is not swamp,” the book begins. “Marsh is a space of light, where grass grows in water, and water flows into the sky. Slow-moving creeks wander, carrying the orb of the sun with them to the sea.”

Cloaked under the narrative of Kya’s survival, Owens writes a love letter to the marsh. But there are moments of clumsy over-romanticism. Two men from town fall in love with Kya (“gorgeous, free, wild as a dang gale”) in what feels old and reused. While her beaus, Tate and Chase, are compelling, harsher critics will call them flat and predictable.

But who can blame Owens? The marsh itself, portrayed tenderly in Owens’s softly-pulsing voice, calls for romanticism. As Kya boats through the marsh’s many-limbed waterways, fishing and digging for oysters, sleeping with the gulls and learning from fireflies, collecting feathers and shells and abandoned bird nests in her wanderings, the words become a sort of enchantment.

Owens camouflages her own life within Kya’s story. As a young girl living in southern Georgia, Owens was encouraged to explore oak forests and hike amidst true wilderness; as a zoologist, she traveled to the African Kalahari for 23 years to study lions, hyenas and elephants, the experiences of which culminated in three nonfiction books —“The Cry of the Kalahari,” “The Eye of the Elephant” and “Secrets of the Savanna.”

Owens infuses nature into her first novel with the lush coastal marsh of North Carolina, intimate with “floating mat[s] of duckweed” and “quiet tongues of foam.” While some of her prose falls heavy-handed, it is hard not to be delighted by Owens’ and Kya’s simultaneous celebration of nature.

“When you can feel the planet beneath your toes and the trees moving about, you must listen with all your ears, and — I promise — you will hear the crawdads sing. In fact, it will be a chorus,” Owens writes.

While Kya’s story is delicately written and the murder element is entertaining, the two narratives intertwine in a disappointing climax. Owens’ characters become dull and mechanical, moving through the motions; readers stop caring about the murderer’s identity or what happens to Kya. Certain scenes are inserted to conveniently explain things, chopping up the prose and coming across as clumsy.

As Owens’ fiction debut, “Where the Crawdads Sing” very nearly deserves all of the praise it has received. Although the ending falls short of brilliant, the rest of the novel is truly beautiful, saturated with an intense sincerity and throbbing whole-heartedness. “Where the Crawdads Sing” is beautiful and imperfect, all at once — and as Owens describes the marsh — “an organic jumbling of promise and decay.”