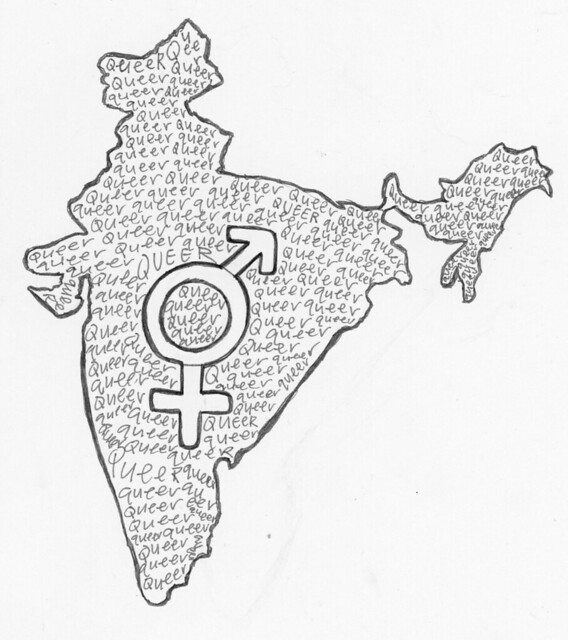

Decolonizing the Indian LGBT+ reform movement

May 7, 2019

Being religious and being queer can often times come into conflict with each other. I am often told that my religion does not justify a “certain, unnatural way of life.” But as a Hindu, I find this connection false and ignorant, explained by a westernized change of Hinduism.

The term “westernized” seems to be a double entendre in reference to society and culture. On one hand, it is used to describe when a region or person becomes more liberal or open to new changes. However, it can also be used to describe inherent “whitewashing” in reference to a culture.

There’s a sense of national pride when a country outside the U.S. adopts a pro-LGBT stance. “They are being like us.” We associate “us” with “modernized” and start thinking countries that are not currently accepting as backward.

However, associating backward in terms of a country’s LGBT+ stance shows the hypocrisy of many western countries and ignores their past.

According to an analysis performed by the International LGBTI Association, of the 71 countries where same-sex relations are illegal, more than half are a result of British colonization. Yet, most of the countries based in the United Kingdom decriminalized sexual activity by the early ‘90s. Throughout most of the 20th century, these countries have lacked agency and independence.

Even as many countries begin to slowly decriminalize homophobic laws, the socially instilled belief that was promoted during colonial times holds true to many in those countries.

My own origins reveal as much. India’s historical relationship with the queer community extends from its origins in Hindu mythology. My obsession with the convoluted relationship between India and the queer community started with Shakuntala Devi’s book “The World of Homosexuality.” She was one of the first to write about homosexuality in India and is regarded as one of the first to study the relationship. Devi’s stance stressing the decriminalization of homosexuality was overlooked at the time, but represented an early desire to end anti-LGBT+ imperial law.

The book begins with a historical analysis of ancient India and homosexuality. Devi cites the “Kamasutra,” considered one of the world’s first writings on the arts and science of sex rooted in ancient Hindu treatise, as the beginning of the documented relationship between homosexuality and India. The writing has a chapter titled “Auparishtaka,” which highlights the sexual relationship between eunuchs that often involved homosexual intercourse.

Hindu mythology takes aspects of queerness and gender fluidity even further; from the beginning, deities being able to change their gender have been a common mechanic used in religious stories. Temples with statues that feature homoerotic imagery between women are a spectacle of acceptance in ancient India. Epic poems that depict same-sex unions of deities really prove the blurred lines between masculinity and femininity in a pre-colonized India.

The Indian anti-LGBT stance started with the British Raj’s implementation of Section 377 during the 1860s. The law, which criminalized gay sex, marked the start of anti-LGBT+ sentiment in India.

Victorian-era colonial rule promoted the idea of “family values” and the “nuclear family” while trying to erase everything considered unnatural. Promotion of a heterosexual marriage while demonizing those who do not fit that mold has dissolved the fluidity of gender and sexuality that was modeled in ancient India, and it seems that only recently India has started legally recognizing the legitimacy of queer individuals.

There’s no point denying that colonialism contributed to the discrimination of the LGBT+ community in India, but is there a point that India, rather than becoming more westernized and liberal, is instead returning back to its roots?

“Decolonization” describes when a region or person becomes independent and undo colonial rule and laws. Imperialism posed a threat to individuals rights and liberties, especially amongst indigenous groups.

India decriminalizing sexual activity for sexual minorities is not their becoming more westernized nor “socially liberal,” rather they are decolonizing the imperial thought that formed anti-LGBT+ sentiment in the first place.

Let’s recognize this: the West did not create homosexuality. They were not the first to show acceptance toward the queer community. They did, however, publicize all their actions as monumental social feats.

That’s where the hypocrisy lies—we establish this dichotomy between western and non-western, and we associate the West with “acceptance” despite historical atrocities.

There is an apparent messiah-complex; we demonize countries that have a different governing mindsets even if societal acceptance has nothing to do with it. Islamaphobia and anti-communism are other examples shown through the negative stigma put on “sharia” and “commies” that stem from pro-nationalism that embolden such prejudice.

It would not be surprising if 20 years from now countries like France and the U.S., who have a very vocal anti-Muslim population, immediately start forgetting this discriminatory past and start pointing fingers at India for also having strong anti-Muslim sentiment.

The false sense of security created by these countries is detrimental. While the U.S. is relatively accepting of the LGBTQ+ community compared to many other countries, it isn’t totally accepting of them.

Anti-trans rhetoric that emphasizes banning them from the military and defining them out of existence shows the limits of toleration. Setting that precedent in terms of Muslim acceptance, the instilled social stigma against them guarantees that Islamaphobic sentiment will always have some precedent in the U.S. even after the law states they are “equal.”

The West tries to propagate itself as the safe haven for minority communities as a method of hiding internalized prejudice that continues as a result of problematic foundations.

India is not backwards for being slower in terms of societal acceptance of the queer community; this dichotomy that is emphasized between the West and non-westernized countries continues a false stereotype that some places are behind or inferior. It’s important to recognize the history behind every country’s relationship with the LGBT+ community because there are far more intricate than the laws associated with it.

Ignorance of these issues pushes a false narrative about these countries while pushing a more problematic narrative about the Western ones: acceptance by law does not always mean acceptance by everyone, and even if countries like the U.S. are more friendly to the gay community, is not justified to believe in a static binary that differentiates the West from anyone else.