Sustainable solutions take root in the form of new zero-waste products and services

Broken down financially, the Zero Waste movement is both accessible and economically monumental.

April 8, 2019

As the Green New Deal and studies about warming trends raise concerns about climate conditions and environmental issues, the zero-waste movement is bringing awareness to the issue of food and resource waste, marking a trend of increased sustainability in the United States.

Bring Your Own (BYO) Container grocery stores are hoping to combat single-use plastics, packaging and food waste by providing an alternative method for buying food. BYO Container stores function on the basic premise of providing bulk foods — such as dried fruits and vegetables, tea leaves and coffee beans, grain and flour products, nuts and seeds, oils, pasta and even bath products — for customers who want to bring their own jars, glasses or cloth bags for their purchases. Their container is weighed and the measurement is subtracted from the final weight to ensure shoppers only pay for the consumable goods.

Grocery stores founded on sustainability began gaining popularity in Europe, where stores like Day by Day in France and Ekoplaza in Amsterdam encourage bringing containers for bulk goods and shopping for unpackaged products.

While BYO grocery stores for bulk goods have already been established in Europe, their presence has been gradually growing in the United States. Although the first zero-waste grocery store in Texas closed last year after opening in 2012 (Arizona Daily Sun), the growing presence of other BYO Container grocery stores suggests the concept is gaining popularity. Notable stores like Precycle, the Filling Station, Simply Bulk Market, the Refill Shoppe and Central Co-op have popped up in New York, Colorado, California and Washington, but others are gradually appearing in other parts of the country. One of the newer shops — Roots Zero Waste Market in Idaho — stated that they intend to open in late spring of this year on their Facebook page.

Just as other countries were quick to adopt solutions, they were also quick to identify the problem of food waste. France became the first country to ban grocery stores from tossing produce and other items approaching the dates on their “best-by” stamps in 2016 (The Guardian). The U.S. has also taken action with policy, with the EPA reporting in September 2015 the intent to reduce current food waste quantities by 50 percent by the year 2030. German media source Deutsche Welle (DW) recently reported on Germany’s intent to meet the same standards, and the Australian government claimed the same goal at their National Food Waste Summit.

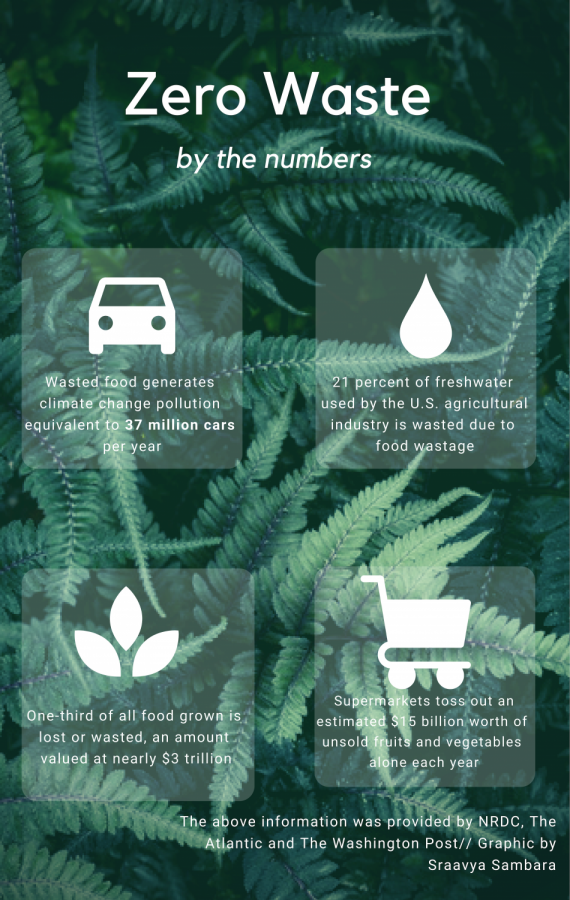

While other countries have taken action to reduce food waste, it remains a sizeable problem in the U.S. — but not in the way that some would think. Most food is rejected before it even reaches the shelves, let alone a plate. According to the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC), 40 percent of the produce produced in the U.S. never reaches consumers, resulting in losses of $165 billion annually.

Unsurprisingly, all the generated food waste has significant environmental and social consequences. Wasted food means wasted resources; according to a report by the NRDC, 21 percent of the freshwater used for agriculture in the U.S. may be spent unnecessarily growing crops that are never consumed. Food waste in landfills often compound in anaerobic or hypoxic conditions, generating emissions that account for 2.6 percent of the annual output of greenhouse gasses.

Salvaging the food that never reaches a dinner table has also proved to be a major lost opportunity for reducing food insecurity, as the NRDC reports that 42 million Americans still struggle with this issue.

With these statistics, tackling the issue of generating less food and plastic waste feels overwhelming, which perhaps accounts for the recent popularity of more approachable, consumer-based solutions for those looking to move towards sustainability.

The BYO Container movement is not alone in its mission to reduce waste, and there are other companies centering their sustainability efforts around reducing waste in the the food industry. According to their website, Imperfect Produce — based locally in San Francisco — offers home delivery of “healthy, delicious fruits and veggies for about 30 percent less than grocery stores” and has devoted itself to ensuring the 20 percent of produce in the U.S. that is discarded before transport to a grocery store can be put to use. Other companies like Loop deliver reusable containers of products between customers, sanitizing and refilling them for each use (CNN).

These new services are part of a growing “zero waste” movement, marked by social media challenges, dietary changes and bans on single-use plastics. They all seek to prevent waste from accumulating in landfills or incinerators, and they comprise a larger attempt to reduce society’s growing anthropogenic carbon footprint. Whether BYO Container stores will become a more permanent aspect of Americans’ lifestyles or fade as a passing trend is still unknown, but there is some indication that the increased attention paid to sustainability — that remains the foundation of the zero-waste movement — will remain.

In the rural town of Kamikatsu in Japan’s Tokushima Prefecture, for example, the Washington Post reported that the residents turned to implementing zero-waste practices to dispose of their trash after their incinerator was banned for producing emissions. They are dedicated to recycling processes, and have a center for recycling clothing into new items or reselling them to the community. More locally, San Francisco has been a leader in domestic zero-waste efforts; according to the Washington Post, they manage to divert over 80 percent of the city’s waste away from landfill or incinerators.

At Dougherty, some students are also familiar with the zero-waste movement and have tried to implement more sustainable practices into their lifestyle.

“Other than recycling — which most people do — I compost food scraps that I have, as well as tea bags because I drink a lot of green tea. We compost all of that because it’s all organic material that can be broken down, and they release methane when they are incinerated in landfills,” senior Kara Sanghera, explained.

Sophomore Sarah Yao explained her motivation to live a more sustainable lifestyle, describing some of the changes she implemented after learning about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and other plastic pollution-related environmental effects.

“One of the easiest plastic-free changes was ditching plastic water bottles as well as plastic straws and utensils. I use a bamboo or metal set of utensils when I can and bring around a Hydroflask all the time,” she said. “I’m continuously trying to encourage my family to develop this waste free ideology. We’ve swapped plastic grocery bags for cloth, [are] buying fewer single-use plastic items and trying to spread the waste-free belief to others.”

While there is much still to be studied about the zero-waste movement and how accessible it is for low-income communities, it’s generally a good indicator that the philosophy often requires less consumption of goods overall, which could cut costs. Junior Eman Arellano cites increased mindfulness as a major contributor to saving money and altering his consumer habits.

“After implementing more zero waste practices into my life, I noticed that I tend to save money, mainly only because I am only buying things that I truly need,” Arellano said. “Now I am more aware of what I’m buying instead of unconsciously spending.”

Chemistry and AP Environmental Science teacher Mrs. Annie Nguyen elaborated that making certain changes, although they may initially create additional expenses, can save money over the long-term.

“Like the recent popularity of Marie Kondo’s “Konmari” tidiness method, it may feel at first like a lot of discarding of disposables and replacing with newly purchased reusables. But after initial investment cost, I think we learn to buy less and reduce the waste that occurs later when we discard. There are a lot of similarities between both lifestyles in that the focus should be on buying things that you won’t need to buy again later. There’s also a whole subset of zero-waste that involves DIY consumables, like shampoo, soap, makeup, etc. Again, higher cost for initial investment, but lower cost over time.”

While certain aspects of the zero-waste lifestyle can be considered to generally reduce costs of living, other adjustments — such as subscribing to programs that aim to reduce waste like Loop or Imperfect Produce — might be unrealistic investments for those at lower socioeconomic levels. On the plus side, current research also indicates that a zero-waste approach may yield some solutions to food insecurity. According to NPR, the same 2016 law that effectively banned food waste in French supermarkets helps ensure that grocery stores account for 50 percent of all donations to 5,000 food banks and charities throughout the country.

Some have expressed hesitancy about the growing prevalence of the zero-waste trend in America, believing that a desire for convenience will reduce incentives to make certain lifestyle changes.

“I feel that convenience matters most to Americans; we want our goods fast, and we want to eliminate any possible inconvenience to get what we want,” Arellano said. “Bringing our own containers and bags isn’t the most convenient option. The only way I can see BYO Container grocery stores doing well in the U.S. is if single-use packaging materials are banned from grocery stores.”

By contrast, others believe BYO Container grocery stores and other services are likely to see success, especially with increased awareness of climate change and other environmental phenomena.

“I definitely think that stores are going to spread across the U.S. because there’s been so much media coverage and attention in light of environmental preservation,” Yao said.

Although zero waste may still seem too complicated to some, there are smaller life changes that can have a big impact. Sanghera cited composting, using less water and reusing cooking oil as some of the seemingly simple actions that can have a large effect if a commitment to conservation is undertaken on a large scale.

“There are little things that everybody can do,” Sanghera said. “No one has to be as drastic as my family has [been]. If everyone did that collectively, it would lead us to a more sustainable society, because it would lead to much less waste.”

Ultimately, while the future of BYO Container supermarkets and zero-waste enterprises and services is uncertain in America, the zero-waste movement signals greater societal consciousness and intent about environmental impact and solutions to food insecurity, as well as an awareness of how consumer choices impact the markets and services around them.