Hear from Another World: Holocaust survivor Paul Smith still suffers 90 years later

January 24, 2019

“I think the Holocaust is always going to be with me … My own family was murdered there.”

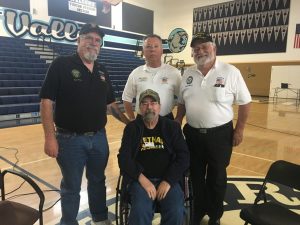

He sits across from us in a worn, cerulean armchair, his wizened hands laced together on his lap and his translucent, lightly hazel eyes fixed on an impenetrable spot in the distance. His wrinkles are a map of his past: a journey across three continents and nine decades to find a home after the Holocaust took his away from him. The memories crush him. But they also define him.

This is Paul Smith*.

A journey across three continents

One morning in 1936, Smith wakes up in his childhood home in Königsberg, East Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia) to find that several extended family members are crowded in the living room and that his father has disappeared. His mother, not telling him why, soon packs him a bag and takes him — her only child — to a Jewish children’s home in a town on the other side of Germany.

Smith has heard about the recent power grab of a man named Adolf Hitler, who has been targeting the Jewish population in his promise to redeem Germany after World War I. But the 8-year-old can’t connect the dots to understand that his father has been kidnapped and that the relocation of his extended family to one house is simply the first step of the “Final Solution.”

Smith was raised in a Jewish household in the heart of Germany just as Hitler was rising to power.

The children’s home, although traumatic and confusing for an 8-year-old Smith, is integral in his escape from Germany. Hitler’s regime is slowly closing in on him and his mother, and during his stay in the children’s home, she is able to acquire emigration papers to London, England.

Her efforts are just in time. Only a few weeks later, much of their remaining family in Germany are sent to concentration camps by the German Schutzstaffel.

However, the war continues to follow the two Smiths to their new location; just as they arrive in London, the Blitz begins. As a result of the bombings, Smith is once again forced to pack his belongings, including a gas mask, and move, this time to the countryside parish of Beaconsfield to stay with an English family.

For the first time since he had left his home in Germany two years earlier, Smith feels relatively safe. In England, Smith soon learns to speak English and makes several friends at school. His mother, who has to stay in London, writes postcards to him during the weekdays and visits him on the weekends.

However, their time in England is cruelly cut short by yet another immigration crisis, and Smith’s mother must find another country to take them in. World War II has officially begun, and Europe is not safe anymore, especially for a young, vulnerable Jewish boy.

In the summer of 1940, Smith finds himself in a Liverpool convoy heading to Valparaíso, Chile. The journey is long, strenuous, and riddled with danger as German submarines attack their vessel multiple times during the crossing.

Finally in Chile, Smith continues his schooling while his mother starts a business to finance their livelihood. He learns yet another language, Spanish, to keep up with the curriculum and ploughs through the rest of his education up to the 10th grade. Upon his graduation, he finds a job to support himself.

However, Smith’s attention is soon caught by what many Chileans revere as “the land of opportunity” — America.

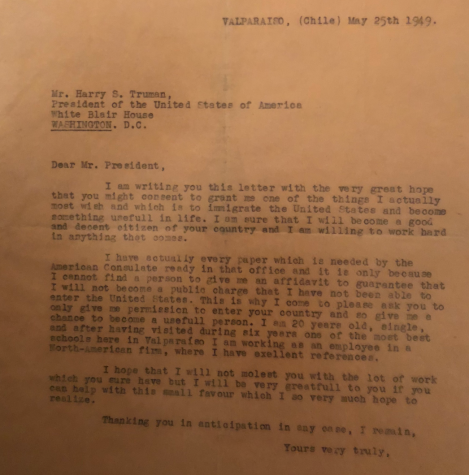

In 1949, Smith addressed a request for an immigration visa directly to the White House.

In hopes of actualizing his recently forged American Dream, Smith visits a number of U.S. embassies in Chile to apply for an immigration visa. But every time, his requests are dodged, ignored or redirected. Acting on promises made by the immigration officials, Smith transfers all his Chilean currency to an American bank, writes hundreds of application letters to employment agencies in New York and begs relatives to sponsor him — all to no avail.

With all of these attempts having failed, in 1949, Smith writes an earnest letter to the one person left whom he believes could help him: Harry Truman, president of the United States of America.

The letter to Truman is a miracle. Within two weeks, he is accepted into the Chilean office of the American embassy for the first time.

“[The consul general] said to me … ‘I hear you’re corresponding with the president … Bring me your passport. You’re getting an immigration visa to come to the United States,’” Smith recalls.

Between Judaism and Presbyterianism

Judaism had always been deeply ingrained in Smith’s life. Smith came from a traditional Jewish family, attended a Jewish school during his childhood in Germany, and remained faithful even in the predominantly Roman Catholic Beaconsfield.

However, his religious commitment was tested in Chile, where members of his English boarding school relentlessly bullied him for being Jewish. Racial epithets such as “dirty Jew” and “Christ killer” were directed at him on a daily basis by students and teachers alike.

It was this persecution that drew him to the U.S., where he believed he could finally escape the torrents of hatred directed toward him. When he reached America in 1949, Smith finally made the decision to cast off his religion, the part of his identity that had been targeted for so long.

“I don’t like to say it, but I did leave my religion for a while, for a long time … I went through so much as a kid that when I came here, I just wanted to leave anything Jewish [behind].”

Through the next couple decades of his life, Smith remained disenchanted with his Jewish faith. It was several years into his six-year auditing job in San Francisco before he was finally directed toward religion again. This time, however, it was not Judaism.

“Somehow, someone told me go and take a look at the Baptist Church* in San Francisco. And I went there on one Sunday morning. And something just happened in me … I just became so happy and satisfied, and I thought I finally found something that accepted me.”

The following Sunday, he attended a Presbyterian service. Gradually, religion found its way into his life again in the form of an Evangelical faith.

“Everybody accepted me; everybody made me feel at home … they were just wonderful. I made a lot of friends, and I have a lot of good memories of all those years I spent in the Presbyterian Church,” Smith said.

But as he had feared, his family and other Jews did not receive the news that he had adopted the Presbyterian faith well. The distant guilt nagging at the back of his head was harshly intensified by his relatives’ slurs, addressed to him in multiple letters.

With all of Smith’s family members being Jewish, his brief conversion to Presbyterianism was ill-received and condemned by many relatives.

“If a Jewish person … finds out that I had converted to [the] Presbyterian Church … they feel that I’m a traitor, to their religion. I’m a traitor to the Holocaust. And I remember I had some family members in Brazil who wrote me very nasty letters when they found out … one person who was married to my aunt said … ‘you don’t change religions, like you change your dirty shirt,’” Smith recalled solemnly.

Throughout those six years that he spent working in the auditing sector, Smith continued to attend Presbyterian congregations.

But shortly after becoming a teacher and moving to Walnut Creek, he began to rekindle a relationship with his original faith, helped by his eventual elevation to a honorary member of a local synagogue.

“It was the first time that I went back to Judaism … I never felt right [about] what I had done, I had just left it … I never felt completely comfortable. I always knew something is right here with me,” he said.

Since then, Smith has remained with Judaism and his synagogue. Nevertheless, his experience with Presbyterianism has left a palpable impact on the things and the people in his life that bring him joy.

“I was watching the funeral service, a memorial service, this morning of Senator McCain. And they were singing all the hymns that I used to sing in the Presbyterian Church, you know, all the big Christian hymns; they sang all of them. And I had just tears going down my face, you know, because I remember singing all those songs for many, many years.”

A life surrounded by death

“The Holocaust is in me, but it has left me alone. And the things that I worry about the most … you will be surprised … what worries me the most right now, for example, is: Who’s going to bury me when I pass away? I don’t have anybody.”

As someone who has witnessed the deaths of so much of his family — and is now waiting for it himself — Smith has a complex relationship with death. He talks of the Holocaust in a resigned manner: resigned to live with it, resigned to accept that it has happened.

But on his own end, Smith’s tone is more accepting, expectant. Above all, he approaches his own death with an overarching sense of gratefulness for the life that he has lived.

“I have no regrets. I’m thankful that I got through that Holocaust, very thankful. And my mother always mentioned it to me, to be thankful that ‘I was able to save you.’”

Forgiving the Nazis

Smith was never an eyewitness to the burning of the Jewish synagogues and stores, the confiscation of his family’s house in Königsberg, the wartime bombing of his hometown, the concentration camps at Auschwitz nor the nighttime kidnapping of his father. But the consequences of these happenings scarred him deeply, forever leaving him with a childhood bombarded by questions and doubts, devastated by fear and loss.

To many Holocaust survivors like Smith, coming to terms with such experiences after the war is the first step toward recovery. The second step is forgiveness, a step that Smith is still struggling with today. After losing so many family members, he finds it extremely difficult to put his religious conviction of forgiveness above the personal grudges that he bears against the perpetrators of the Holocaust.

“A number of people have asked about forgiveness. I don’t know how to answer that. I believe in God … that there’s somebody up there. Whether I can give forgiveness, that’s up to Him … Usually the church likes to forgive. For me to forgive is very, very difficult,” he said.

His ambivalence toward forgiving the Nazis is paralleled by an underlying distrust for other Germans of his age — those who were alive during the time of the Holocaust. Aligning with popular opinion regarding the resolution of World War II, Smith noted that the Nuremberg trials convicted and sentenced far fewer people than were truly culpable for the Holocaust.

“Whenever I meet a German person — and I’ve met a number of German people, of my age or even older — I always feel very uncomfortable … because I always wonder … ‘what did you do during those years, where you were supporting Hitler and all that he did … the six million Jewish people that he murdered?’”

After the Holocaust and before her death, however, Smith’s mother had always approached their existence with optimism. She counted blessings in their escape and survival from Nazi Germany to England, then to Chile and finally, for Smith, to the United States. Seldom discussing the unspeakable atrocities committed in the Holocaust, she took great care of her remaining possessions, property, and family.

Eventually, Smith’s mother chose to return to her home country, assured by the new German Democratic Republic (East Germany)’s multiple apologies and laws defending its Jewish people. Similar to Smith’s experience with being denounced as a traitor after his conversion to Presbyterianism (see “Between Judaism and Presbyterianism”), his mother immediately experienced harsh backlash from family and the Jewish community.

“After being for 30 years in Chile, [my mother] went back to Germany and people said, ‘How could you do that? … How could you go back to Germany, where your entire family got killed?’” Smith recalled.

Although he does not know the current state of his old house — it was likely destroyed by a British bombing attack on Königsberg in 1944, and it lies in a territory that was ceded to Russia after the war — Smith himself has returned to Germany multiple times. One visit was to his mother’s apartment shortly after her death.

Smith disagrees with the Jewish taboo of Germany as the land of the Holocaust, but he very well affirms that he has not forgiven the Nazis. And if he ever does, he says that it will be of God’s volition, not his.

Life in the States

Once in the U.S., Smith worked in New York City before being drafted into the U.S. special intelligence forces in 1951 for the Korean War. Although he was eager to serve the country that had accepted him so wholeheartedly, he was never summoned overseas, and his two years of service passed quickly.

On a whim, after he heard some friends speak fondly of the distant state of California, Smith decided to attend UC Berkeley, a privilege granted to veterans by the G.I. Bill of 1944. After hitchhiking his way across three states, attending a junior college in the Bay Area and scraping funds together to support himself in college, Smith graduated with a major in auditing.

From there, he held a stable — but in his opinion, monotonous — auditing job at a CPA firm in San Francisco for many years before realizing in 1962 that his passions lay in teaching.

With his fluency in multiple languages, Smith spent nearly 30 years between Clayton Valley Middle School, Pleasant Hill High School and Northgate High School as a Spanish teacher before retiring.

From behind the armchair that Smith is sitting in, we see that the day has aged and the sky has turned gray. It has only been hours, but decades have passed in our dialogue.

With his life laid out on the coffee table between us, we have but one question left. When he hears it, Smith looks up at us behind cloudy eyes. A sad smile spreads across his face.

“That I survived it?”

Smith lets out a deep, long sigh.

“Oh gosh, no.”

*Subject and church names have been changed for privacy.