“The Strange Library” review: exploring the peculiar

February 2, 2017

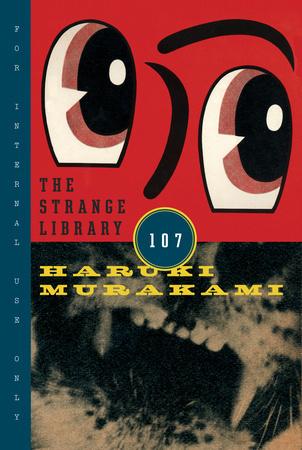

Artful, effortless diction, colorful whimsy and an elaborate nightmare form the foundation for Haruki Murakami’s “The Strange Library”, originally published in 2005.

The Japanese author’s other works include “The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle”, “1Q84” and “Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World”.

I am a new – perhaps even tentative – fan of Murakami’s work. I have found his novels, while often puzzling, to be incredibly compelling and “The Strange Library” is no exception. I found the length of this book particularly intriguing. How could an author convey such an obscure tale in fewer than 100 pages? His book is perfect evidence of the strange genius of Murakami, who has proven that an elaborate and enjoyable story is indeed achievable in half the length of a typical novel.

The stand-alone version of the peculiar novella was published in 2008, and spans a mere 96 pages. This book, however, should not be mistaken for an easy read, Murakami’s “The Strange Library” is riddled with idiosyncratic characters and filled with complex creative genius layered within what may seem like a only confusing short story.

“The Strange Library” follows an unnamed narrator who is sent to “Room 107” while searching for books on tax collection in the Ottoman Empire. In said room, he meets an elderly man who imprisons him in the “Reading Room”, a prison-like chamber deep within the library. The narrator is told to memorize three large books in one month to win his freedom.

“Readers will quickly recognize the elements of one of the grimmer of Grimms’ fairy tales. They also will note that stories that take place in a basement are likely plumbing psychological depths,” writes Claire Hopley (The Washington Times).

The narrator meets a mysterious, unnamed girl and the meek sheep man, who, as his name suggests, is clothed in a sheep costume. He serves as the prison guard for the young narrator, and reveals to the boy that the only thing that can be expected at the end of his time in the library will be the consumption of his brains by the old man, much to the narrator’s horror.

“‘You got dealt an unlucky card, that’s the long and short of it. These things happen,’” remarks the sheep man (Murakami).

Understandably frightened by the gruesome possibility of his brains being “slurped right up”, the narrator decides to orchestrate an escape from the library, along with the sheep man and the girl.

The perplexing nature of the novel both entices and startles, and Murakami’s consistent and liberal distribution of anomalies within the pages do not fail to captivate. The author even incorporates topics such as the existence of multiple realms.

“Our worlds are all jumbled together — your world, my world, the sheep man’s world. Sometimes they overlap, and sometimes they don’t,” remarks the narrator (Murakami).

He manages to find a balance between youthful and innocent characters and the grim, dream-like world from which they attempt to extricate themselves. Murakami utilizes the contrast to weave an intensely odd realm that encourages your mind to dwell upon the novella long after you’ve set it down.

“And the story itself, full of characters and images both awfully weird and utterly down to earth, transforms as you read it, becoming a living, nearly talismanic exercise in how to lift yourself out of the realm of the ordinary and allow the sentences to carry you into an alternate universe,” commented the late Alan Cheuse (NPR).

Indeed, this novella succeeded in developing the strangest (but most intriguing) library I have ever found myself lost within. Despite the macabre nature of the institution, it is nonetheless worth an exploration, as immersion in the works of such an author is an experience that should not be missed.