“I could do that.”

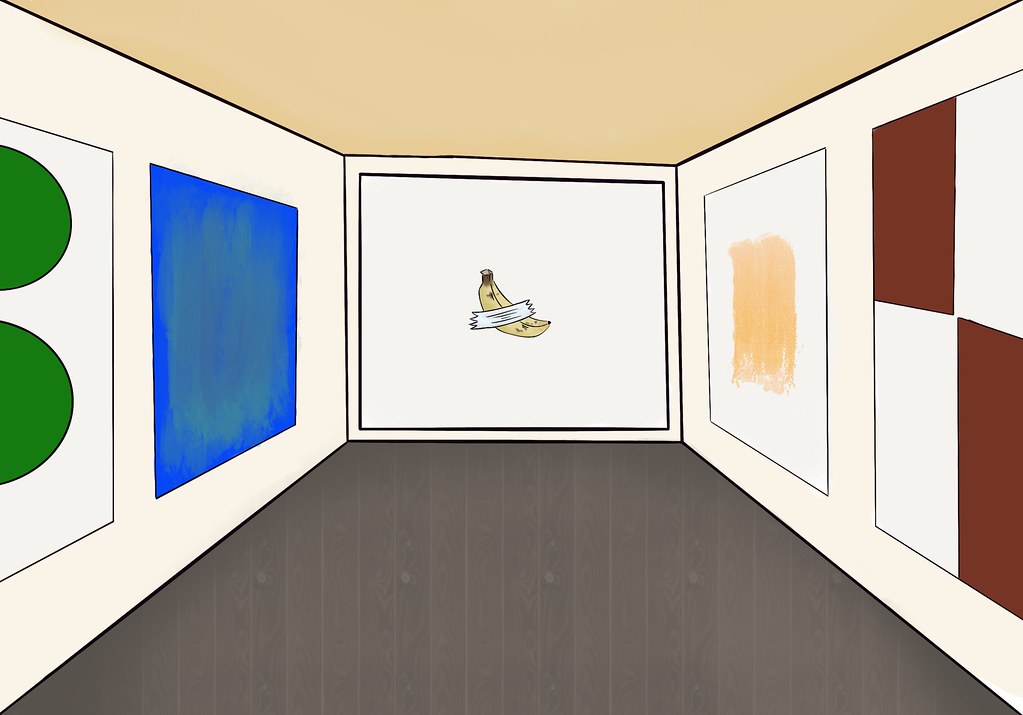

It’s a phrase often heard from onlookers coming across a work of modern art. It might be a blank canvas, a tiger shark preserved in a glass tank or maybe even a banana fixed to the wall with duct tape. One quick glance and the piece is dismissed, ridiculed and shrugged off without a second thought. It’s not hard to see why — you probably could do that. But did you?

In this day and age, the artistic value of modern art is being increasingly denied, with more and more people criticizing it for being overly simplistic and lacking any real meaning. The chasm between the artistic value attributed to modern art and the value people actually find in it stems from the differing standards of what constitutes a “good” work of art. What may be profound and thought-provoking to one person could be absurd and meaningless to another.

First off, to truly understand the subject, it’s important to recognize that many people mistakenly use the term “modern art” as a catch-all term. Most of the time, when they say “modern art is bad,” they’re actually referring to abstract conceptual pieces that lack any apparent effort. But in reality, modern art is a broad label that refers to works produced during the period from around the 1860s to the 1970s, and is commonly confused with contemporary art. The point? It’s unfair to renounce the entire movement based on a narrow slice of it. Not to mention that people with limited knowledge of art tend to misconstrue contemporary art as what they believe is modern art.

However, the value of modern art goes far beyond surface simplicity. In defense of the abstract and conceptual pieces, more than a few come to mind to bring to discussion. Take “Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III,” for example, a painting made by Barnett Newman between 1966 and 1970. The massive painting is almost entirely red, with thin stripes of blue and yellow at the edges. Reactions to “Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III” varied, with people either loving or hating it.

In 1986, tragedy struck when a man slashed the 18-foot-long painting with a box cutter, allegedly motivated by a dislike of the artwork’s abstract nature. It was only then that “Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III” garnered close attention from the public. The restoration of the painting, involving house paints and a roller, hacked at Newman’s immaculate brushstrokes. It lost a part of its soul that had made the painting so unique, and people noticed immediately — the rich red hue from before was gone. Newman’s work would never be the same again. Ironically but poetically, the destruction of “Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue” made the painting finally complete.

It’s easy to get caught up in the apparent simplicity of abstract art that we forget about the historical context of the pieces. Artists respond to the times they live in, whether that be war, politics or cultural shifts. Modern art as a movement formed during a large shift in artistic values — a rejection of rigid realism and an embrace of abstraction and other unconventional forms. Modern artists shattered the world’s status quo and chose to represent something in a new way. They weren’t just painting differently, but also thinking differently, and the same can be said for artists today.

Styles of modern art, like impressionism, cubism and surrealism, emerged as a countermovement to traditional techniques that made realism easier, including the advent of photography. Especially considering the popularity of AI in the current world of art, realism has become more and more obsolete, making abstract ideas all the more valuable.

Now, I won’t sit here and pretend that all works of modern art are breathtaking masterpieces, and that I can make sense of them all. But that’s true of any movement. People tend to pit one art era against another as if it were a competition, which shouldn’t be the way to understand human endeavor. Art was never meant to be interpreted in any single way, and we have modern art as living proof of that.

So the next time you encounter a work of modern art and think “I could do that,” take a step back. Maybe the value isn’t in the doing, but the daring.