The other day, I stumbled across a TikTok where a young woman was talking about a new book she’d read, and at first, this seemed like it would be right up my alley. The book was one I’d been meaning to read for a while, the first novel in the series “Six of Crows”, and considering that it was a wildly popular book with a great reputation, I was interested in what she had to say about it. However, things quickly took a turn when she held the book up to the camera, clearly unhappy as she mentioned that she’d started the book last night and was up to page 34.

“Can we talk about something real quick though?” she’d said, tapping the book over and over with her nails. “Why are the pages so filled with so many words?…I like pages that aren’t filled with this many words, like literally every page, is like. Like, look at this!” She then held up the open book, gesturing towards the pages, which were, admittedly, filled with words.

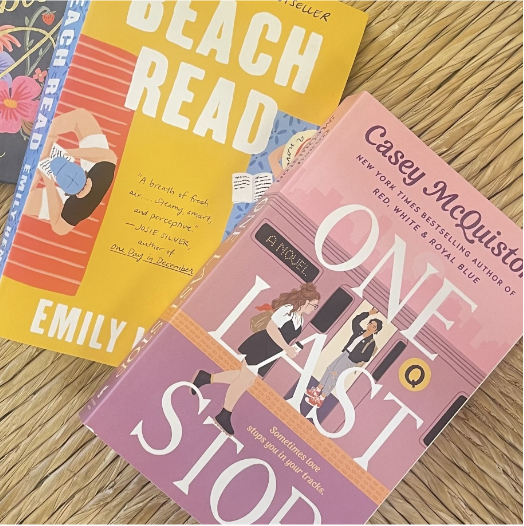

“BookTok” is a community on TikTok dedicated to reading. It’s known for being predominantly made up of young women and heavily focused on reviewing and recommending new releases. Generally, the community rallies around 3-4 books a month, making them sell out in bookstores everywhere and making authors blow up overnight. Titles that have become household names due to BookTok’s influence include “It Ends With Us” by Colleen Hoover and “A Court of Thorns and Roses” by Sarah J. Mass. In theory, it’s a great concept that benefits new, up-and-coming authors, and readers, who get to be introduced to books they may never have heard of otherwise. The way BookTok’s popularity has helped bookstores like Barnes & Noble can’t be overstated either. It’s undoubtedly a good thing that supporting them has become trendy.

But it quickly becomes clear that BookTok’s problems far outweigh its benefits. While it has been credited with getting many young people into reading, part of why it accomplishes this so effectively is because of how TikTok’s algorithm is designed to cater to short attention spans. Research from the University of California, Irvine, has shown that the average time someone spends looking at one thing before losing interest and switching to something else has gone down from two-and-a-half minutes to only 47 seconds. The decline in people’s attention spans coincides with the rise of short-form content, which is designed to make you spend as much time as possible scrolling through numerous one-minute videos.

BookTok is guilty of this as well. With little time to grab the attention of viewers, people who make one-minute reviews often describe literature as nothing more than a short list of tropes, making sure to use keywords that will be favored by the algorithm depending on pop culture trends. Over time, this practice has reduced the way people on BookTok read to nothing more than a search for these things, completely ignoring more complex elements of novels, such as characterization, theme, and plot. This is part of the reason why low-quality novels are becoming more and more popular. BookTok isn’t designed to measure quality of writing, it’s designed to turn reading into its own form of fast fashion, where trends are cycled in and out faster than anyone can keep up with.

Books that get popular on BookTok also tend to share the common characteristic of being lower-level when it comes to the content itself. These novels are often easy to read and digest, which isn’t inherently problematic. However, it happens to coincide with dwindling reading comprehension rates, which is worrying. 54% of adults in the United States read at a literacy level below the sixth grade. This has only gotten worse over the last few years, and like the issue of attention spans and how TikTok only contributes to the problem, social media platforms have been criticized for encouraging a lack of media literacy through algorithms that show people extreme positions with an overall lack of nuance.

Authors and publishers have also learned to produce their books this way in order to turn a profit, often writing stories based on punchy, marketable tropes, with plotlines taking a backseat because they know that’s not what their primary audience is there for. It’s turned into a never-ending cycle that reduces the art of writing to an algorithmic game. As ironic and rage-inducing as it was to see someone with a book review account talk about how a book’s pages contained too many words, it’s hard to blame her when this line of thinking is a result of how books are sold, marketed, and discussed on BookTok as a whole.

Listen, I’m someone who reads a lot, and the majority of what I read isn’t generally granted the title of “good literature”. Some of my favorite authors include ones that write at a mostly middle-grade level, or write books that belong to less serious, “sillier” genres. So I’d be the first to tell you that the literary community can be snobby. It’s gained a reputation for gatekeeping while operating like an exclusive club of intellectuals with a high barrier to entry. Because this way of thinking is so prevalent, criticisms of BookTok are written off as examples of this pretentious pseudo-intellectualism. And this is true for a few of the points often brought up, such as critiquing the genres it popularizes and the majority of BookTok’s readers being young and female. However, many of the larger implications of BookTok suggest that its issues go far beyond not fitting the literary community’s traditional criteria.

BookTok can make good, legitimately valuable books popular. I enjoy many of the novels and authors that got their rise on TikTok too, but the way people read is shifting towards something that negates its primary benefits, and no matter how you look at it, that’s not a good thing.