We’ve all read those vigilante stories. One man pitted against the world, doing what everyone considers wrong, for the greater good. In fact, we tend to side with these characters, admiring their bravery, respecting their ability to stand against the crowd, wondering how this fictional society could be so stupidly blind to their cause. Knowing that this civilization may collapse, if it does not heed the warning of the daring main character.

Then we close the novel and return to our daily lives.

But what if this was happening in the real world, right now? And what if we, the “society,” were turning a blind eye to the motivations of these young vigilantes, choosing instead to focus on how absurd their performance of activism may be?

Throughout history, activism has come in many forms. Often peaceful, activism can take place through art, boycotts, resistance movements and public demonstrations.

But activism can also be violent and destructive. This type of activism is often the last resort. When nothing has been working for decades people will often turn to violence.

Eco-vandalism is the newest form of “destructive activism,” focusing specifically on fighting the travesty of climate change, often involving art. Eco-Vandalists have thrown food and paint at well known paintings, even going as far as to glue themselves to museum walls.

Recent victims of this form of activism include Edward Degas’s “Little dancer aged fourteen” and the renowned “Sunflowers” by Vincent Van Gogh. In November of 2022, up to 11 eco vandalism incidents occurred, which considering that eco-activists target famous works of art, is a lot.

Many members of the public, especially artists, may gasp upon reading about these incidents in the news. To their tremendous relief, they would then discover that the original piece is never irreversibly harmed.

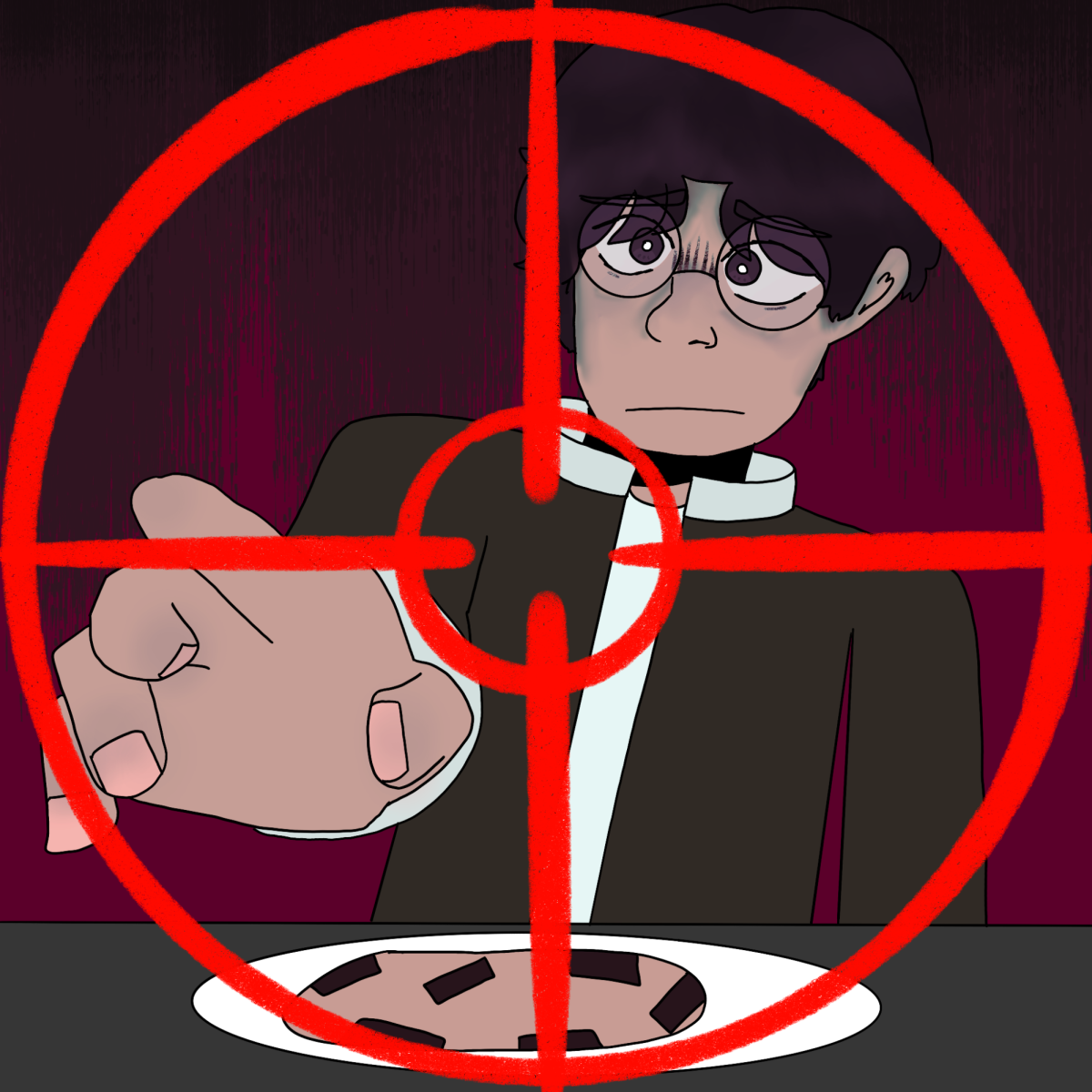

Let’s inspect this closer. Is this a result of strict museum security, or are eco-vandalists actually targeting works of art that are protected?

We must remember that these are people who don’t want to pay a million dollars for damaging a painting. It boils down to this: the eco-vandalists are not trying to actively destroy works of art, but rather demonstrate their anger with recent world issues regarding climate change.

Speaking of irreversible damage, guess what’s happening to the Earth right now?

It’s ironic that a lot of arguments people against eco vandalism serve up can be applied to the Earth itself.

Some may point out the immense monetary loss that would occur, if an original painting were to be damaged. The recently vandalized Van Gogh painting itself is estimated to have a worth $40 million. If a drop of tomato soup were to grace the canvas, the museum would face a tremendous financial loss.

What about climate change? Hasn’t it already caused 165 billion dollars in damages in the United States alone? What about the countries that are less equipped to handle the ever increasing amount of floods, earthquakes, tsunamis, heat strokes and droughts we are dealing with?

And who exactly are the people who have to pay for these damages when climate change comes knocking at their door? Certainly not you, me, or the museum. It is an established fact that climate change disproportionately affects low-income communities in the United States, in addition to having adverse effects on third world countries. After Pakistan was faced with devastating floods in August of 2022, an estimated 9 million people may have been forced into poverty.

In fact, as I am typing out this article, Libya is being hit by floods that have already taken 5,200 lives. What economic state will the victims of these floods be left in by the time you are reading these words? How many people will have lost their homes? How many people will have lost their jobs and their livelihoods?

How many paintings will have tomato juice dripping down their protective glass cases?

At the rate we are going, one day, the Earth will be destroyed. Stripped of its trees, its rivers choked out by pollution. Perhaps we’ll have moved onto other planets by then. Perhaps there will be a mother, telling her child a story before tucking them into bed.

She’ll tell them about the planet her grandparents came from, how all its beauty was siphoned away, bit by bit. She’ll talk about the things called “trees,” and “tigers,” and “lakes.”

And she’ll tell her child how there were some people, screaming the name of a planet that needed saving, how they were ridiculed, jailed, and ignored.

The little child will drift off to sleep, wondering why no one ever listened to their cries.