Stop brushing period problems under the rug

The birth control pill exists as a control agent rather than the solution female adolescents are in need of.

February 2, 2023

It wasn’t until I (Nayja) was told that I possibly needed a blood transfusion that I realized the gravity of my menstrual issues. Having begun my periods in fifth grade, there were already a few red flags in my relationship with menstruation. But mild cramps were often brushed off as “natural” or “common,” and so was the irregularity in my cycles. Only in seventh grade, when I began feeling faint and suffering from splitting headaches, were the concerns over my periods taken seriously. After having bled heavily for a few months, my hemoglobin levels were terribly low, and then the crimson flags were finally blaring.

It took numerous doctor appointments, a ton of questioning and bleeding nonstop for about three months for my physicians to finally give my issues the attention they deserved. And in no way does this imply that my physicians were trying to downplay my issues. The problem is more multilayered, but it stems from the stigma against female biology, especially when it comes to that time of the month.

For countless female adolescents like the four of us, this experience sounds quite familiar. In fact it’s almost the norm.

“When you first get your first period, your body takes some time to figure it o deut. When someone gets their first period, it’s not 28 days later that they get the next period, usually, it happens within the next two to three months,” explained Doctor Joanne Vogel during an interview.

But after the first time, it is a different story.

“If you have a period, and then you go longer than three months without a cycle, that’s usually the time that is good to reach out to your doctor,” Vogel added.

Unfortunately, for most menstruating people, reaching out to doctors isn’t as fruitful as imagined. With little variety for pathology in gynecology, our menstrual issues are often pushed off till the last minute and a dangerous card is dealt.

“I went to doctors quite frequently, [but] I was never diagnosed with anything. Every time I go, they just tell me that whatever is happening to me should not be happening to a normal teenage girl, and [they] advise me to go on birth control,” an anonymous student, who faces severe side effects due to her periods, explained.

Even at DV, heavy bleeding and irregular periods pose a prominent hindrance to students’ daily lives.

“Every time I start [my] period, [the] first day is always just throwing up and having really bad cramps. I [go] to the nurse’s office at school every single month,” the anonymous student explained.

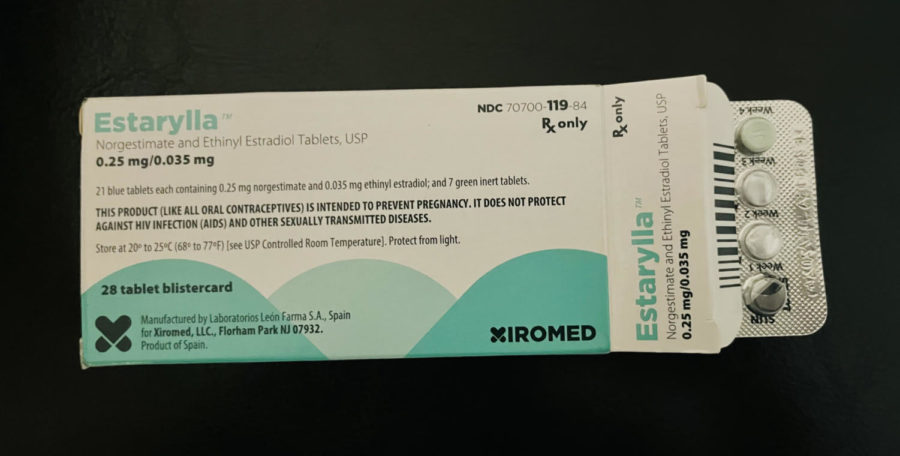

Too often the solution to menorrhagia and similar menstrual issues is a birth control or hormone pill: drug treatment.

“Birth control gives you hormones, in a controlled fashion,” Vogel explains. “So with younger people, we’ll put them on the birth control pill for a shorter period of time, like three years to get through that initial period of time where their body’s figuring it out. And then they go off the pill and they’re back to normal.”

But going back to normal is not always ideal, especially when normality is undefined and possibly even dangerous. Normality could mean healthy period cycles, heavy bleeding, menstrual irregularity, or even no period at all.

“Once you’re off the pill, it doesn’t correct anything anymore, and you’ll go back to whatever your new normal state is. It’s just controlling the symptoms while you’re on the birth control pills,” explained Vogel.

And needless to say, that scares us.

But more than the uncertainty of the pills, we can all be sure that every woman’s body is different. Birth control pills (BCPs), which are only one solution, definitely won’t be the ideal solution for everyone. This is because the side effects that arise from taking BCPs can vary from person to person, to the point where the side effects are even worse than menstruating symptoms.

According to Brown University, “BCPs can make users slightly more prone to form blood clots [and] can raise your blood pressure.” They add that BCPs “have been associated with an increased risk of forming benign liver tumors.”

The risk of these side effects, for most people, far outweigh the consequence of dealing with irregular periods, bringing them back to square one. As young students and menstruating people everywhere struggle with their cycles, the medical world serves up more ways to sweep our period problems under the rug by stalling the symptoms instead of actually acknowledging the elephant in the room and tackling it.

It is 2023 and we live in a world that realizes new medical innovations daily. We are working towards 3D-printing organs, modifying genes, and furthering work on artificial hearts. Yet, our period problems still wait on the back burner. That should be obvious, as we can’t even call menstruation by its colloquial term without mentioning “that time of the month” or “the shark week.”

Can we fix this? Undoubtedly, we can.

Are we, though, as a community of intellectually complex and moral beings ready to tackle period problems? That is something we are uncertain of.