SRVUSD students and teachers weigh in on utility of ATP program

Sunny Kim

Academic Talent Program (ATP) is a gifted education program that places elementary to middle students with similar abilities under a differentiated curriculum. Meant to be more rigorous and in-depth than General Education, the more beneficial aspects of a unique learning community must simultaneously balance questions of competition, divisiveness and labeling.

September 27, 2022

Each year, a new batch of elementary school kids begins the sorting process into gifted and talented education.

Students identified as “high-potential learners” or possessing “advanced abilities,” according to the National Association of Gifted Children, are selectively chosen to participate. Selection is usually done through testing measures such as the Cognitive Abilities Test (CogAT).

In SRVUSD, CogAT is administered to all second-grade students in the second semester of the school year. Students who receive a national age percentile rank above 98 on the CogAT test qualify for Gifted and Talented Education (GATE) identification. From there, a CogAT score that has a Local Percentile Rank in the 97th percentile, as well as other assessment measures such as a writing sample and a teacher recommendation, may qualify them for the district Academic Talent Program (ATP).

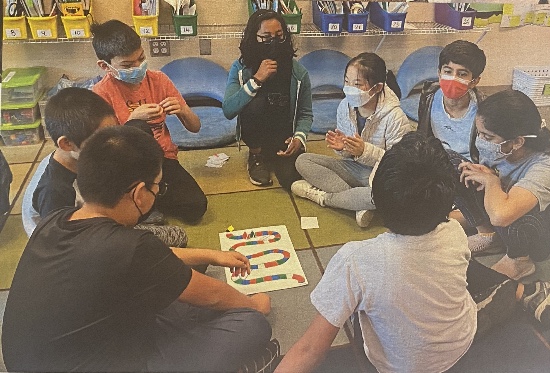

ATP is a magnet class for the top percentage of GATE-identified students, bringing together students from different home schools to learn in a homogenous classroom setting. The program spans from fourth to eighth grade and takes place at Bella Vista Elementary School and Windemere Ranch, Gale Ranch and Diablo Vista middle schools.

Yet gifted and talented programs are hitting rocky ground across the nation. In October 2021, New York City scaled back its current gifted and talented program, eliminating the city-wide testing of four-year-olds for gifted qualities. In SRVUSD as well, elementary school ATP classes were concentrated from Golden View and Tassajara Hills to only two sections in fourth and fifth grade at Bella Vista.

SRVUSD students and teachers in the ATP program believe it still represents the best option for gifted learners. However, they express concerns of treating ATP as more of a label than an opportunity.

ATP’s purpose

For DVHS senior Avantika Pandiyan, who was in ATP from fourth to eighth grade, the program isn’t so much for the “smart” kids as it is a place for those with similar mindsets to learn together.

“I don’t think it is necessarily because they are students who are more successful, but it’s more about grouping you with people who have very similar attitudes,” she explained.

Pandiyan elaborates, stating that in third grade, before she entered ATP, she was “bored out of [her] mind.”

This could explain why, despite being offered only to GATE-identified students, the district frames ATP as a “special needs” class, as noted in their ATP middle school orientation presentation to families in March 2022. “[ATP is] a place for students who thrive in a challenging environment,” the presentation states. “Similar to special education programs, [it’s] for students who regularly demonstrate need and desire for [a] different learning setting.”

Patrice Norris, a fourth grade ATP teacher at Bella Vista who has taught the program for 12 years, corroborates this.

“We have general education, which is your typical fourth grade class, and then on the other end of the spectrum we’re meeting the needs of the highly or profoundly gifted with ATP,” she said.

As such, there’s a consistent overall emphasis in ATP on being with like-minded students to facilitate depth of learning.

Educational aspects of ATP

The same California State Standards that outline General Education classes form the educational basis of ATP. However, with more project-based learning and a focus on critical thinking, Norris explains that ATP gives students a deeper exploration of the existing curricular topics.

“A lot of people think ATP has to do with tearing through the curriculum. It doesn’t — it has to do with developing specific skill sets, allowing students to create their own projects,” she explained.

Although the program follows the same educational standards as General Education classrooms, Norris believes ATP offers gifted students more support.

“The Gen Ed teacher is working with a big range of students … Whereas this class is a homogeneous group of gifted students, so we’re able to work with a different methodology and a different pace,” she added.

For DVHS senior Isaac Liu, the educational depth of ATP left a helpful impact.

“English [in ATP Core] specifically made me do pretty well during English 9. During ATP we did a lot of writing-based projects and assignments, and we learned how to do things like write TIQAs. Those are important skills for English,” he said.

Windemere Ranch Middle School sixth grade ATP core teacher Kirstin Souza, who has taught ATP for seven years, notes that ATP students generally go into the program already equipped with certain at-standard skills, which feeds into the way she teaches things like writing.

“I go quicker with ATP kids and my expectations are higher because they’re generally more prepared to write. So by the middle of sixth grade, they’re already really writing at seventh grade standards … and by the end, it’s even exceeding that,” she said.

Souza mentioned that many of these educational benefits stem from students’ intrinsic desire to learn.

“We’ll be talking about something and I’ll say, ‘I’m not really sure.’ The kid who grabs their Chromebook, or who wants to go and explore right there in that moment — those tend to be the ones that are more intrinsically motivated,” she said. “They’re like, ‘Wait, that’s really interesting. I want to know more,’ and they’ll dig deeper.”

As a result, learning pathways that Souza would offer only as options to her regular classes, she pushes as opportunities for ATP.

“Sometimes I might give maybe two or three choices in the General Ed class but then in the ATP class, I’ll add a couple of additional choices. So like a poster versus a 3D model versus maybe some kind of skit where you write the script … versus creating a mini documentary versus a podcast,” she said. “Because there just seems to be a depth of creativity that sometimes I don’t get in the General Ed class.”

Similarly, Norris pushes her students to explore learning at a deeper level instead of staying at the surface level of the curriculum.

“Once we get done with the required curricular aspects of fourth grade, we’re able to go deeper and spend much more time on a topic,” Norris explained. “For example, in social studies, an extension and enrichment activity is that we are involved in National History Day, a three month project where students deeply research a topic of their interest, through learning how to develop a thesis statement and support their thesis statement. That’s not your typical fourth grade curriculum; that’s extension and enrichment. We cover all the curriculum, but then we move into areas that allow us to think deeper or really work on critical thinking skills within that fourth grade curricular framework.”

Although this project is mandatory for all ATP students, Norris believes it encapsulates the greater depth and breadth of exploration that students in ATP can achieve.

Social aspects of ATP

Students in ATP stay in a common cohort through elementary and middle school depending on when they entered the program. As a result, ATP offers students a unique learning community by allowing them to remain with the same group of classmates for many years.

“There’s pluses and minuses to it. It really does feel like a family,” Souza said. ”I can see that it makes people feel safer and more comfortable in the classroom when you’ve been with people for so long. But I also know that if there’s that person that you don’t necessarily mesh with very well, that it can make things a little more uncomfortable.”

Pandiyan found a group of friends in ATP that lasted well throughout high school. But despite maintaining that these tight-knit friendships are “the best part” of ATP, she believes it’s still beneficial to branch out from the ATP bubble.

“I think it’s good to have people who participate in various interests,” she said. “All of us are very similar, so you’re kind of always like, ‘Oh my God, I’m stressed about my GPA.’ And then [your friend in ATP] is like, ‘Oh, me too.’ But when you’re with someone who’s not [in ATP], then now you have a different perspective, and I feel like I like spending time with people who aren’t like me.”

Liu holds a similar viewpoint, noting that he appreciated his classmates’ academic drive but would have liked the opportunity to meet more diverse groups of people. Meanwhile, DVHS senior Aadhav Prabu commented on a noticeable behavioral difference between ATP and General Education students.

“ATP kids are more pretentious,” he admitted, noting that it’s easy to think of oneself as “better” due to being set apart. “But then I came into high school and I was like … it doesn’t matter. There are a lot of kids outside of ATP that perform better than kids in ATP.”

A competitive atmosphere

Norris and Souza’s love for their work is palpable. Yet, both ATP teachers noted that there are still downsides in the form of competition within the classroom.

When people of similarly high academic output are put together in the same classroom, the resulting phenomenon is something Norris calls “academic jockeying.”

“Students [are] trying to feel each other out and [see] who’s smarter than who,” Norris explained. “That’s the culture that I don’t want [in] my classroom. We’re all learning together. We all have gifts, and we’re all individuals and we all have certain gifts. So I take a lot of time working on the social-emotional kind of environment in this classroom — that we all have gifts, we’re all here to learn differently.”

Souza agreed that though she tries to defuse the sense of competition, having students of similar academic ability in the same class makes competition hard to work around.

“I try to say, ‘You need to think about your own strengths and your own areas that you want to drill in and challenge yourself, and the only thing you should compare to is yourself and being better the next time just for yourself,’” she said. “But having said that … people may be feeling like they don’t measure up.”

The gifted label

ATP students are a noticeable sub-group of elementary and middle school cultures. From the separate classroom to the common cohort, ATP kids often wear the program as a label, intentionally or not. Sometimes, pushing young kids to reach this “gifted” status can lead to drawbacks, as Souza explains.

“I do think that being labeled gifted becomes like a badge of honor,” she said. “Sometimes I feel like that can be more of a distractor than just a learning opportunity. Sometimes it does create a rift between friends.”

At the end of each school year, Hidden Hills Elementary School second-grade teacher Michelle Erlick writes recommendations for all the second-grade students with ATP-qualifying CogAT scores. But she does so with a sense of resignation, adding that besides the way that kids treat the label, she finds the label itself is given a significance that it shouldn’t have.

“I have a problem with one assessment determining a future like that. If I give a math assessment, and a student doesn’t pass it, does that mean they should get an F … on their report card? One assessment?” she said incredulously. “I think most students and most teachers would say, ‘Well, no. There’s so much more.’ So I do have a problem with one test determining the future of a fourth and fifth-grader. I think there has to be more than that.”

Prabu points out a different issue.

“The actual opportunities that I got from ATP, the extra experiences and things outside the scope of a normal class — I think those were valuable to me,” he said.

However, he is skeptical of the need to separate these opportunities out purely for ATP students.

“It creates this unnecessary divide between ATP and non-ATP students,” he said. “I think the program itself is a good concept, like you want to give these extra learning opportunities. I’m just [wondering], why do you have to limit that to people that are so-called ‘more academically talented’?”

In recent years, Prabu’s sentiments have been increasingly mirrored by the district. Whereas ATP students used to have sole access to certain field trips, Toastmasters leadership conferences and special labs — a heart dissection among these — Souza notes that the district has stopped offering ATP-exclusive opportunities in favor of equity.

The future of ATP

With the competition, labeling and divides created by the program coming under scrutiny, it’s worth questioning if the benefits of ATP outweigh the costs.

For Souza, she’s seen that parents frequently push their kids to strive for ATP just to attain the label of being gifted. Oftentimes, this comes at the expense of considering if their child would really enjoy or benefit from the ATP program.

“Let parents know that it’s okay for kids to be kids and it doesn’t always have to be such a strong academic focus. Kids are going to learn, right? And so maybe if the community shifts focus more with the whole child as opposed to just the academic child, that could make a change,” she said.

Others argue that the future holds no place for ATP.

“A student isn’t smart because they’re gifted; it’s about the opportunities they get,” Prabu said. “[ATP takes] already-gifted students and gives them opportunities to make them more gifted. But then why shouldn’t less gifted students get those opportunities that can make them more gifted?”

His conclusion?

“I think they should get rid of the ATP program … and GATE as a whole,” he said. “They should try to provide these opportunities to a larger group of students instead of limiting it.”

Much like Prabu, Erlick would like to see all students raised to the same educational standards rather than separating students out into ATP. The existing separation prevents what Erlick views as a beneficial intermingling of a range of learners.

“I think [ATP students] don’t get to be leaders and help with kids that need their help. And the kids that are [in General Education] don’t get to learn from them and see how they think and [realize], ‘Maybe I could have thought that way,’ and be introduced to new things,” she explained. “So I would like to see the future of it [as] no CogAT test, no ATP classes.”

With this alternative, Erlick questions the necessity of differentiating students. Much like the oft-debated idea that students who are given positive affirmation end up doing better, she wonders if ATP implicitly enforces the opposite.

“What if we told all students that they were good enough to do everything? By telling them at such an early age, ‘You’re not the best’ — do we stump that and make them feel like, ‘Well, then why bother?’” she said.

It’s possible that what’s needed is a revision of the California State Standards to encourage deeper curricular exploration for all learners. Instead of sorting students out into gifted programs, it could be a matter of changing the current educational structure to naturally ingrain depth of learning for everyone.

On the other hand, Norris feels that the continuation of ATP is integral for gifted learners’ success.

“Do I want to see this program go away? Absolutely not. Unless someone could tell me that every single fourth and fifth and sixth and seventh and eighth grade teacher is going to meet the highly gifted needs of those students,” she said.

That being said, Norris would like to see improvements in the way people approach ATP.

“Definitely get rid of the word P in ATP,” she said. “I’m not teaching a program. I’m meeting the needs of the kids that are in my classroom, most of whom tend to be highly gifted.”

The program has been around for at least 35 years, according to Norris, and as such, it’s difficult to predict if it will significantly change in the future. For now, new cohorts of bright-eyed students will enter classrooms like Souza’s and Norris’ each year, where teachers will be ready to nurture them. Meanwhile, those who did not qualify or who chose not to go will continue to learn, accumulating their own unique experiences in the process. But whether their personal growth — and those of the gifted students next door — will be helped or hindered by ATP education is a matter up to interpretation.

From her experience, Souza maintains that programs like ATP hold significant value for gifted learners.

“When you have a truly gifted student, you do need to give them those opportunities, because chances are some of these kids know things well beyond anything I’ve ever known or will ever know. I think when that’s not recognized in education, for somebody who does have the ability and the knowledge and the desire to want to learn more and go deeper, sometimes that can be stifled,” she said. “Having identification of giftedness for truly gifted students, I think that benefits them in education. Because when educators know that, it allows them … to give that child the freedom to learn and grow deeper.”

The question is if, for all students, that kind of identification is worth it.