The skill of delay empowers and decieves

Productive procrastination can have positive side effects, despite the stress that may result from it.

March 15, 2022

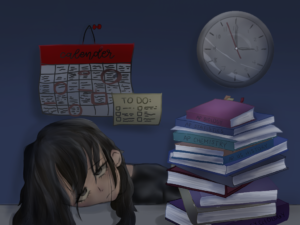

I’m writing this introduction at 2:25 a.m. on a Wednesday night (or Thursday morning, I guess). I have a lot of things I could be doing right now besides sleeping, the most sensible activity. Starting a project due in two days that was assigned almost a week ago. Writing an update to a college that I told myself I would finish two weeks ago. Emailing a teacher I meant to reach out to before winter break. But in spite of all my looming tasks, I’ve decided that now is the perfect time to finish this op-ed about procrastination that I started over two months ago when I was procrastinating on my college applications. Welcome to my life. An endless cycle of procrastination.

If you don’t have a negative perception of my work ethic based on my overly-honest introduction, you’re either a procrastinator yourself or blissfully unaware of procrastination’s reputation in society. To parents, procrastination equals laziness; there is no debating this assertion. “You can’t get this done the night it’s due, so make sure you start early!”— a warning teachers repeatedly attach to assignments. Even among the high school and college student population—the demographic heaviest-hit by procrastination—there’s an overwhelming guilt and unspoken shame associated with procrastinating, especially if the outcomes are not promising.

These negative attitudes are what shape the general consensus surrounding procrastination: it’s a sinful, self-destructive habit of unmotivated slackers.

But that stereotype misses a hidden side to procrastination: productivity.

Yes, some people procrastinate by watching the latest episode of Euphoria. Or by scrolling through TikTok for hours. Or by napping in the middle of the day (Obviously, I am not speaking from personal experience.) But there are also less noticeable behaviors that classify as forms of procrastination: voluntarily cleaning your room, doing homework for one class to avoid homework for another, etc.

These habits comprise the tendencies of productive procrastinators; an unexpected group of procrastinators who avoid important tasks by completing less immediately pressing tasks. Contrary to stigmatized conventional procrastinators, Dr. John Perry, Stanford philosopher and author of “The Art of Procrastination”, argues that productive procrastinators are “useful citizens” that have “a reputation for getting a lot done.”

But what motivations are responsible for this overlooked breed of procrastinators?

“Anyone can do any amount of work, provided it isn’t the work he is supposed to be doing at that moment.” That’s Robert Benchley’s theory. A renowned 20th century actor, writer, and self-proclaimed productive procrastinator, he admitted to building a bookshelf and writing a response to a 20-year-old letter to put off writing an article on deadline.

Our brains are wired to avoid work: the limbic system is responsible for our prioritization of short-term happiness; it’s what draws us away from the unpleasantness of working until we absolutely have to (for example, at 11:58p.m.)— that’s when the prefrontal cortex takes over and finally kicks our brains into work-mode. So technically, it’s natural to procrastinate. But the short-term happiness we get from putting off work cancels out with the regretful awareness of actively procrastinating for productive procrastinators. That’s why they are steered toward tasks that still require producing output rather than just sitting around doing nothing. In short, they want to feel useful without doing what they have to.

Intertwined with this want is the desire for perfectionism. In a meta-analysis of procrastination’s causes and effects conducted by University of Calgary Dr. Piers Steel, procrastinators indicated the following feelings: stress regarding evaluations (both individual and external) of their work and fear surrounding failure.

Alice Chen, a freshman at Stanford University, self-identifies as a perfectionist procrastinator. The most recent assignment she procrastinated on? A rhetorical analysis paper; with a three-day weekend to complete it, Chen waited until 10p.m. on the last day to start (and finish) it.

“The task itself was daunting. But also if I started earlier, I would’ve been much more picky with what I put down. If I do it at the last second possible, I just go with everything I say as long as they seem like semi-valid points,” Chen said.

I’m the same. I often push myself to the very last minute with my assignments because I’ve convinced myself it’s the only way I can get work done. Chen and I both seek self-satisfaction. We want to feel accomplished, but we’re afraid of failure and mediocrity that doing the work we’re assigned has the potential to result in. So, we replace what we have to do with what we want to do: low-risk tasks that still make us feel highly useful. For me, laundry is the perfect escape. It’s a mindless task that doesn’t require much mental or physical energy to complete, yet it still grants me the sense of satisfaction I crave because it’s a necessary, organizational (and somewhat therapeutic) chore. If I have a Statistics test to study for, I’ll conveniently gain a sudden urge to wash every single one of my hoodies. If I have an English paper to work on, I’ll still choose to fold my clothes over research.

Consciously, I know that studying the night before my test probably won’t end well. But if I get a bad grade, it’ll be because I didn’t study much, and not because I’m just not smart: my fragile ego is protected. Vice versa, if I luckily don’t do as bad as I expected, it’ll have to be attributed to my intelligence since I didn’t study that much. Similarly, I know that cramming my English paper the last few days before the deadline will temporarily destroy my sanity. But at least the fear of turning it in late finally setting in forces me to commit to my writing rather than let myself lament over its imperfections any longer.

Psychologically, my procrastination fools me into believing that I’ve successfully avoided the feelings of discontent that come with poor performance and unsatisfactory quality of work. And even though I’m aware that I’m being tricked by my own conscience, I’m oddly not deterred from my stubborn attempts to avert self-disappointment.

Evidently, productive procrastinators may not be motivated by the best reasons… such as the overwhelming need for self-validation. However, we shouldn’t disregard productive procrastination’s potential positives. Relatively, productive procrastination is still more beneficial than conventional procrastination.

“I’ll procrastinate either way, so I should procrastinate by doing Math rather than watching another episode of a TV show,” Chen said.

Though I would never ask to find out, I’m sure my parents would agree that reading a book is a better form of procrastination than wasting time on “that damn phone.”

If I’m going to put off something regardless of what I do, I’d rather get work done or learn something new to make myself feel better about not using my time properly.

Occasionally, productively procrastinating can be better than not procrastinating altogether. Some people choose to procrastinate in the “gray” area of productive procrastination and conventional procrastination by channeling their energy into creative outlets like art or music. Or taking long walks while listening to podcasts— my preferred medium of leisurely-productive procrastination. Not only are these activities already beneficial towards mental and emotional health by nature, they also grant the doer a unique workspace to be calmly alone with their thoughts.

“When we finish a project, we file it away. But when it’s in limbo, it stays active in our minds,” Wharton management and psychology professor Adam Grant wrote in his article “Why I Taught Myself to Procrastinate”.

It’s precisely the allotted alone time productive procrastinators allow themselves to brainstorm that results in success. One of Grant’s former students conducted an experiment to prove just that. A group of people were instructed to come up with business ideas. Some were instructed to begin immediately (non-procrastinators). Others were allowed five minutes to play Minesweeper or Solitaire (procrastinators). Afterwards, the procrastinators’ ideas were deemed 28% more creative than the non-procrastinators’ (when rated for originality by independent evaluators.)

“Procrastination encouraged divergent thinking,” Grant concluded, affirming that the extra time taken to start a task allowed for more innovative ideas to arise.

Chen and I both agree this is probably why we prefer to start writing assignments later. They’re usually more “intimidating” because they require more brain power and creative thinking. If we give ourselves the time to think (and simmer in our panic) about a prompt for a while rather than putting pen to paper immediately, we eventually push ourselves to write something that makes some sort of sense.

Additionally, starting off the day with something you’re good at sometimes gives you the necessary confidence to move to other tasks, Chen explained, referencing her productive-procrastinative habit of doing Math assignments before English ones. For me, my confidence-boosting procrastination looks like championing my friends in Word Hunt before I am championed by my Economics homework.

The small “successes” we get from some procrastinative activities make challenging tasks seem less difficult in comparison to what we’ve already accomplished. In this way, productive procrastination is a helpful ego-inflater that encourages us to tackle the responsibilities we’ve felt the most unconfident confronting.

Despite the upsides to productive procrastination, it’s a dangerous habit to become permanent.

“You’re lying to yourself; even though you’re getting something done, it’s not what you should be getting done right now,” Chen said.

Regardless of its conventional or productive, procrastination is still procrastination. By definition, it’s self-destructive and counterintuitive to push off tasks you know that you should be getting done before others.

Eventually, a lifestyle that revolves around postponement will become unsustainable and detrimental. In fact, procrastination that extends into adulthood backfires in unfortunate ways. For example, H&R Block conducted a taxes survey that found people who delay tax filings lose $400 on average due to “rushing and consequent errors”. In 2002, these hasty tax procrastinators were responsible for a surprising total of $473 million in overpayments. Health-wise, chronic procrastination exacerbates the stress and anxiety procrastinators seek to escape because their self-sabotaging behavior eventually drives them too far from their goals and motivations. Productive procrastinators are not immune to these negative impacts; that’s why considering methods to minimize avoidance in the long-term is necessary for all types of procrastinators.

So, how can productive procrastinators break the cycle of neverending delay before it becomes a lifestyle?

Chen is a big advocate for to-do lists.

“Include only 3-4 things, or only 1 thing and break it down into steps that are less intimidating,” Chen explained.

As an avid planner user, I can say that meticulously breaking down stressful tasks into tinier, more manageable parts has helped reduce the temptation to procrastinate.

A more disciplined approach is the “Nothing Alternative”, designed by famous detective novelist Raymond Chandler. While working on his stories, Chandler forced himself to spend four hours everyday either writing or doing nothing. Both were fine, as long as he was not busying himself with other positive tasks (like writing checks or reading magazines), because it meant that his only option was to wait for inspiration to manifest into ideas and/or put them onto paper.

Chandler compared his strategy to the modern primary schooling system: “If you make the pupils behave, they will learn something just to keep from being bored.”

Intentionally doing nothing seems incredibly uncomfortable. But that’s the point. To avert the uneventfulness of nothingness, the willpower to accomplish tasks otherwise pushed to the side arises. Or so Chandler says. If I don’t procrastinate on it, I’ll try the Nothing Alternative sometime this weekend to confirm whether it really works.

As I’m finally finishing this op-ed, I can’t help but laugh at the irony in my volatile work ethic. I started this piece as a productive-procrastinative task, and when I was finally forced to finish the task I was avoiding, I started procrastinating on this article instead. And now, I’m motivated to get it done. Upon completion, I’ll fool myself into feeling temporarily satisfied with myself. Will I experience a wave of anxiety and guilt tomorrow when I’m forced to confront the deadlines I intentionally ignored by working on this op? Probably. But that’s tomorrow’s problem.