The Museum of Us: Viruses and the Definition of Life

Miroslava Chrienova

The definition of life is a human-made construct — and perhaps that offers us clues about the meaning of life.

March 2, 2022

You and I are living. I think.

Right now, if you could just press your palm to the left hemisphere of your chest, and tell me what it is that makes you alive, what differentiates you from that rock over there or a drifting cloud, could you do it?

Maybe you’ll go for the definition we learned in biology, structured by the properties of life: organization, metabolism, homeostasis, growth, reproduction, response, evolution. A neat boundary. A definition.

But definitions are, of course, only a suggestion. A mule is a horse-donkey hybrid and unable to reproduce, yet arguably very much alive.

Yet is it very much alive? What is alive? At the risk of sounding pretentious, I want to meditate and meander with my thoughts for a while. Life is a word, a definition that we pieced together out of observations, experiments and tidbits of science. We are very much alive, but our aliveness is fragile, held upon the stakes of a definition.

The definition of life is blurry because it is, like so many things, a human construct. We made it up. We created the guidelines. We’re alive, but it is only a word. We are living, but it is only a verb.

In 2020, COVID-19 rampaged its way through society – infecting, incapacitating and devastating individuals and communities. As the virus infiltrated our bodies and hijacked our immune systems, I thought they seemed very much alive.

But are viruses alive? An old question, with no absolute answer. For a host of reasons – they cannot reproduce independently, they do not metabolize – viruses aren’t considered alive.

But if they are not as alive as a rabbit, then does that automatically make them as lifeless as a rock? And what of other, “inanimate” beings? Ferris Jabr, on pondering the existence of life, muses on the difference between his brother’s toy rollercoaster and the family cat: “In the end, aren’t they both machines?… But on the most fundamental level, what is the difference between an inanimate machine and a living one?”

“Most people do not consider crystals to be alive, for example, yet they are highly organized and they grow,” wrote Jabr. “Fire, too, consumes energy and gets bigger.”

So it’s an age-old question – and my answer is that perhaps life is a spectrum –, but also a meaningless one. Who cares if a virus is alive? The virus doesn’t care. However we classify it, it’s going to keep injecting its DNA into cells, pumping its proteins, manufacturing its bodies and babies.

Maybe it’s long overdue that we stopped pondering the meaning of life, and leave that weary question to rest. You could say: there isn’t meaning in everything. There isn’t meaning in anything. Humans assign meaning to arbitrary things, and it makes us naive and foolish. We could learn a thing or two from viruses, moving forward in time and carrying out the definition of living, instead of worrying about it. It’s a waste of time and thought. It’s a desperate attempt at hope.

But isn’t there a certain beauty in it? The longing way in which we grasp at meaning, and purpose, and fullness. We hold an old shirt, and it reminds us of childhood. We smell the dried summer grass, and a million memories reinhabit our lungs. We see an oddly-shaped pebble, a plane in the sky, a certain time on the clock — and we make it a symbol, an omen, a sign.

We’re forever interpreting the world, translating it into something recognizable and half-spun from imagination. That’s a bit beautiful. It would be perhaps naive to deny such stubborn beauty.

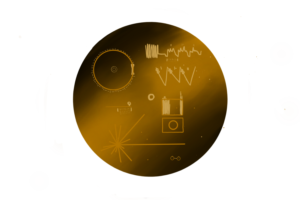

I’m reminded of the Golden Record once again. A small phonograph disc holding pictures and sounds, music and voices, sent into space — space! — with only a feeling of goodwill and hope. Hope that this little spacecraft will stumble into another species from another planet in the gigantic, swallowing brightness of the universe. Always hope.

In the Golden Record, we tried to pack the definition and meaning of life. We said: maybe someone will find it. Maybe they’ll even take the time to unravel the meaning we knotted so tightly into such a small space. Maybe they’ll create as many stories as we did from the faces and textures and feelings of life.

I’ve never heard of anything so naive, so foolish, so despairingly, wholly beautiful as the Golden Record. Everything is meaningless and everything is meaningful and it all doesn’t matter and it all matters very much.

Look at your hands, at your nails growing slowly, at the creases on your palm that we call life lines. Look at how much meaning you can derive from an expanse of skin, a life line: a measure of how long you will be conscious and breathing, an answer to our biggest shared fear — death. Look at how much meaning we stuffed into a definition: a lifeline is a rope used to save lives, a thing which someone depends on for escape, a different answer — life — to our biggest shared fear.

I keep writing paradoxes, and maybe that’s telling. The world isn’t quite as pin-down-able as we’d like to believe. A lot of it is molded in our minds, or borrowed from other minds for the bit of time that we’re here.

If life is just a word, then we live in the connotation.

I’ll leave it up to you to decide what the hell that means.

Sincerely,

Eva