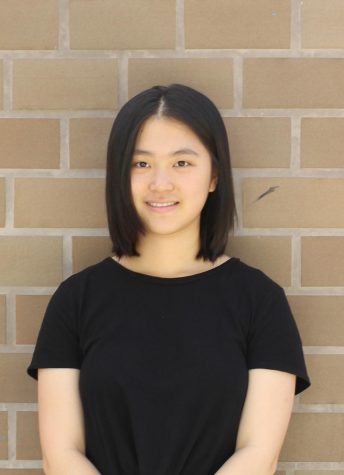

An open letter to young Daniela, the Dougherty Valley student body, and the class of 2021: a failed speech and reflections on privilege, accomplishments, differences & identities

This is my last piece I’ll be writing for the Tribune; I want it to be raw and come full circle. I don’t often talk about myself and my stories, but I want to tell parts of it.

May 19, 2021

I don’t often talk about myself and my stories, but I want to share parts of my stories. The point of journalism is to tell other people’s stories. Ironically, after doing that for a while, you start to reflect on your own experiences. This is my last piece I’ll be writing for the Tribune; I expect it to be raw and come full circle.

High school was a lot for me, as it was for anyone. Nevertheless, some of my struggles were unique. I am different. I don’t live in a million dollar home. I’m a minority within a minority at Dougherty but also mixed. It’s hard to define your identity when you’re white and Latina. There isn’t anyone like you in your daily life. My neurodivergent brain functions differently than someone who is neurotypical; no one teaches you how to fit in when your brain is different.

Sometimes at school, it was almost as if I was the designated “representative from planet intersectional” on queer, neurodivergent, genderqueer, biracial, Colombian Latinas. It’s a lot sometimes.

I wish younger Daniela knew not to listen to the world, but she didn’t understand. I wish our community truly embraced diversity like they preach they do. I think the pandemic sort of leveled the playing field for everyone, especially when it came to perspective. COVID doesn’t choose its victims based on how much money one makes or how much social status someone has. COVID could care less about how many prep classes you take or which summer programs you were accepted to. Nothing is permanent unless people see the shift and try to keep the social attitudes.

Here’s one example of the Dougherty community not being as open I expected it to be:

I was sitting in my AP Literature class during my junior year, having a group discussion. My peers in my group started talking about what neighborhoods they lived in.. When it became my turn, I said, “oh I live in an apartment that’s near (insert a local elementary school here).” Most smiled and said something like “oh that’s cool!”

But one didn’t. She gave me a disgusted, confused look. “Oh, you live in an apartment??? I thought you lived in a house!” I looked back at her, puzzled. I was half asleep, it was early in the morning, and frankly I cared more about the assignment than what she had to say. But after class, the comment just kept replaying in my head over and over. I have access to all the same resources most DV kids do. I live in San Ramon, just in a smaller house. I’m middle class, I’m first generation and my family runs a small business. But somehow that made me “weird” and “different” to this girl.

Sometimes it’s hard to see beyond the bubble you live in. I know people say “I hate San Ramon” and “there is nothing to do besides go to Safeway.” Although this may be true, it’s one thing to just talk about it but another to complain about this, like it’s a bad thing. Living in San Ramon is not something to toss aside.

Our community is statistically safe. Danville SanRamon, a local online news company, reported that San Ramon was recognized as “the ninth safest city in the nation to raise a child”, in Dec. 2020. Additionally, San Ramon was ranked as the “safest community in California for families with children” as San Ramon has 10.27 property crimes per 1,000 residents, 0.56 violent crimes per 1,000 residents, and 0.14 sex offenders per 1,000 residents. San Ramon has drastically smaller crime rates, compared to cities like SF or NYC.

San Ramon was the only Tri-Valley community listed on the 2020 safest cities national rankings. Most families have an immense amount of privilege. Another day, another Tesla. How many communities is that the case in? Your average family home is a million dollar home. Of course, this doesn’t erase any other problems. However, it seems almost absurd that people shame San Ramon without even acknowledging how much of a privilege it is to live here in the first place.

These sentiments of somehow being even more different than I thought I was started to eat at my mind. I felt lost in my identity, even more than I was already. To start off: I had the universal biracial struggle of not feeling fully white but also not feeling fully Latina. Then there’s the fact that I was a minority within a school that has a ton of minorities, just not mine. I got tired of having to explain my identity to people, an identity I barely understood myself. My privilege is that my skin isn’t dark, but I’ve also been asked “what are you” way too many times in my life.

I tried to fit the societal norm and be straight; it didn’t work out. But I am also the same as you. Please treat other people as they are the same and allow space for differences; don’t try to force them into a mold or tell them that who they are doesn’t have a place, unless they explicitly show you a unique part of their life and tell you to treat them in another way.

It only became a matter of time before I would start to ask myself that same question of how to fit a cookie-cutter societal norm. When I started to see the layers of privilege and judgement within my own school that is supposed to be a “diverse melting pot,” it was rather jarring. I already know that based on the labels I carry, I’m the person with the smallest voice who has the most to prove. Yet, I didn’t expect to have to prove myself when I’m constantly surrounded by minorities at school; I expected to be uplifted.

To young Daniela: Struggle is not normalized— it’s shamed. Don’t blame yourself.

I remember sitting in my AP European History class, overhearing students discuss their grades. “Ugh, I got a B. My mom is going to kill me; it’s not like I studied though so I guess I don’t care.” “Dude, same, this is an A-.” I felt a crushing wave of angst wash over me, staring at my scorecard, an F staring back at me. I just told them “I didn’t do too great” and tucked it away.

This was after I did all the homework, took detailed notes, did practice questions and did every single class assignment. I participated in every discussion with the most enthusiasm for learning while staying up until 3 A.M. re-reading the European History textbook. I cried when I got home. This happened multiple times, in many classes; my grades were only held afloat by other things and I always had a good rapport with my classmates and teachers.

But something didn’t click. I told myself that I wasn’t working hard enough, and that I should be like that other kid in my class who gets A’s every time who always says they forgot they had a test that day. This went on for years. I just told myself I wasn’t trying hard enough. The friends that I confided in either tried to relate (but really couldn’t) or listened to me, but didn’t really know how to help. I was otherwise “high achieving” and did a lot, so people assumed I was just fine.

What people didn’t see was my anxiety attack in junior year when the counselor came in to talk about senior year classes; I felt incredibly nauseous, shaky, on the verge of tears. I kept it in and smiled in class. When brunch rolled around, I walked into room 1205, the journalism room, with Ms. Decker and my co-editor Harshi (at that time) who were talking. I unloaded my fears to them: “I’m not getting into college. I won’t graduate high school. I can’t do it. Why is everything so hard? Why do I feel like I try so much and I have nothing to show for it? Why do I suck? I am so stupid, I don’t deserve anything.”

Ms. Decker and Harshi gave me a look of extreme confusion and concern. Looking back, I see why. But in the moment, it all felt real. I thought I wasn’t capable of anything anymore. I was so tired of trying but failing. I was angry that I couldn’t be a typical DV kid that gets all A’s. Dougherty taught me that the other people who were struggling were likely in hiding or in other classes. Fast forward to the end of my junior year when I finally sought help and was diagnosed with ADHD.

It all made sense, not to mention how that going undiagnosed for so long contributes to other feelings like anxiety and hopelessness. However, I was a little mad at myself and the world around me. No one showed me how I could have aspirations and still need support. It took me struggling so hard to realize that I wasn’t even working with tools made for me, no wonder I felt useless. Being neurotypical is a privilege.

All my time spent tutoring and teaching others in academic leadership, I dedicated my time to destigmatizing struggle and needing academic help in school. But I failed to do that to myself; it took a huge mental toll. Struggling is not shameful. I’m proud of it now. But I wish I didn’t shame myself for it, and I wish Dougherty culture accepted how you can literally be the hardest worker but also struggle the most.

To the Dougherty student body: Trying to get into college is not worth being someone you are not – privileges must be acknowledged.

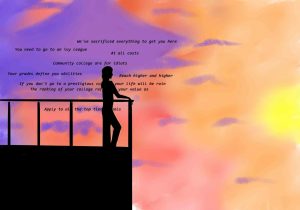

In a recent group chat about college admissions, I dropped my phone in shock; someone said “if you aren’t aiming for Harvard at DV, are you even alive?” Who would think like that? That’s such a dangerous statement that could easily push the wrong person over the edge for all the wrong reasons. Besides, not all people will aim for Harvard. Different colleges are fit for different people; what might be someone’s safety school might be another’s dream school.

People talk about how they “wish they got hit by a bus” so they had something to write about for college essays. Not only is this also maddening but it’s sad; people are wishing for bad things to happen to them just for an elite label. People are asking to be oppressed, asking for trauma, wishing they had a “spicey” or “juicy” life; I see this at Dougherty, even though the school is made up of minorities, where you would think everyone accepts everyone with open arms with no questions asked.

I wish people knew that writing about trauma is harder than you think; it means you have to re-process the event over and over again every time the essay is edited. Not having trauma is a privilege. For people who have traumatic experiences, the essay itself could be potentially re-traumatizing unless it’s something that the person has come to terms with. Admissions officers aren’t stupid, they know how to tell when a student’s writing isn’t fully authentic.

How ironic when struggling with something like mental health at Dougherty is seen as something that should be shoved under the rug.

Sure, call me a hypocrite, I’m going to an Ivy. But I made a choice to not tell my saddest or most depressing stories in my essays. I told the stories that make me who I am, alongside the ones that make the connection between the person I am now and the person I plan to be for me, myself, and I, in the future.

I wrote about the things that have made me stronger, the things that have made me happy, the things that I would rant to a friend about, the things that I would be excited to do, and the things that keep me going. I talked about some of my struggles, but not in a way that would reflect pity on me (I hate pity).

The more raw you are, the scarier it is, I know. But rawness allows you to find your fit, ending up somewhere where you will thrive. Don’t you want to end up in a school that’s cut out for you, waiting for you to be a part of them, rather than somewhere where you feel lost and out of place? Even if there’s a fancy label? The rejections stung, I won’t lie. I got about 20 of them.

But that made the acceptances even sweeter with more physical and sentimental value. In a community like Dougherty, people talk about the value of an acceptance rate like it determines the value of you and your worth, willing to give up anything for it or give up part of themselves. The ability to think that is a privilege. I always had my eyes on an Ivy or top school because it’s been a dream; not because I wanted to make a friend upset or fit in.

It hits differently when you were raised in the first generation; I’ve always valued my education. I know that graduating is a privilege. I know that having the ability to apply to college is a privilege. I know that having the time to write essays instead of working is a privilege. I know that having the reliable technology to write and do all my prep on is a privilege (irregardless of access to a private counselor. I didn’t have that, and that’s a huge privilege).

As my journalism teacher, academic leadership teacher, and mentor for 3 years, Ms. Decker, wrote in a personal piece a couple years ago, “where you go to college does matter, but not for the reason you think;” I kept this piece close to me whenever I went into a college-spiral. I actually did apply to the University of Puget Sound (where Ms. Decker went); they were the first school I heard back from, and they awarded me a 100k scholarship. My reaction was me sobbing for four minutes straight.

The acceptance rate didn’t matter. What mattered was that not only did I get into a great school, but a school saw some amazing potential in me, and was down to give me a scholarship purely based on merit. Cornell saw that potential in me, too (and also gave me the BEST aid, and is covering all my costs to attend their Prefreshman Summer Program). Although I turned down UPS, I still have my letter from them on my wall; it makes me feel warm inside. It’s right above my Cornell early letter, letting me know that I should be expecting an offer of admission on Ivy Day.

I’m going to college, and I can’t believe it. I’m proud of it. I’m going to college because I know the value of a single dollar, and because I want to change the world. Not because I want to fit in. The other night, I was recording a video diary for myself and I said “you know, I’m actually pretty smart. I finally see it.” It made me tear up. My mom cried after I got into Cornell, saying “I used to clean houses with you in a stroller and look at you now;” I was me. I didn’t make myself more oppressed than I needed. I didn’t exaggerate a sad experience. I was raw and authentically me.

I have plenty more stories, I could go on. But these are the ones I wanted to share; my hope is that they can impact someone and help them realize why acknowledging privileges are important. There is nothing wrong with it, we all have some kind of privileges, just some more than others.

Please. Acknowledge your privileges. Please. Own up to the advantages you have. Listen to other people’s stories. Normalize struggling. Be yourself on your college applications. Not only will it take you to where you are meant to be, but it will help other students be the person they are meant to be. I’ll continue to ask my college peers to do this, but this is what I want to leave the Tribune with.

To the class of 2021: Here’s what I want to say.

I’m gonna be shifting the tone a bit. Although this op is about me, I want other people to be able to connect to my message. This year was also exceptionally unique and hard; there’s no handbook on how to survive your senior year in the midst of a pandemic and uncertainty, and I strongly believe this led to a shift in some Dougherty cultural attitudes.

I auditioned to be the graduation speaker. Spoiler, I didn’t get the spot. But that’s alright. I’m fortunate enough to still have a platform. My future roommate suggested “hey, why don’t you publish it in the Tribune?” Not only did I realize my future roommate is a genius but since I was already writing this piece, I realized it could be an awesome addition to it and a conclusion that isn’t angry.

It’s kind of ironic in itself. I want to publish the speech that didn’t get me anywhere almost as a metaphor for how it is to struggle in high school, or at least how it was for me; I had many doors shut in my face and was struggling with self-expression, hence I took it all into my own hands and found my own medium. Anyways, here it is.

How a wildcat makes history: My ‘21 (failed) graduation speech.

“Well, it’s been a long year, to say the least. I asked some of my peers to describe their high school experience in a word or phrase. High school was “frustrating, random, surprising, interesting, chaotic, inconvenient, painful, stressful, regretful, underwhelming, eventful, tragic, toxic, eye-opening, horrible & exhausting’ all at once.” I don’t think it was what any of us expected, nonetheless, during a pandemic. Someone said high school would be rated “0/10” and “would not recommend it.” From my perspective, it was anything but the stereotypical high school experience.

One peer told me that she “never experienced the epic highs and lows of high school football.” Valid, neither have I. But I don’t think any of us came to high school looking for the stereotypical small-town “American” experience with football games accompanied by school spirit or the classic mean girls’ vibes with nothing to do besides shop, gossip, create burn books, and wear pink on Wednesdays. Dougherty is not your typical high school; we live in a bubble, we all have some privileges (and we should acknowledge them).

However, our community is blended & diverse, a collective of stories infused with ambition and the passion for being a changemaker. It doesn’t matter how many AP & honors classes you take. It doesn’t matter how high or low your test scores are. It doesn’t matter how much money your family makes. All Wildcats are uniquely different, each special enough to make history on a plethora of scales.

Think about it: when you logged onto a zoom call for a class, you made history. No one really knew what zoom was before the pandemic. Your first presentation in a remote setting? You made history. The first time you expressed your opinions on remote vs. hybrid learning or the school loop vs. google classroom debacle? You made history. The moment where you pressed “submit” on your college applications in a world where academics are turned inside out? You made history.

The moment where you texted a friend who looked sad during gov on zoom? You made their history. The teachers who worked, and still do, endlessly from their home without extra pay and still checking on their students? You made those student’s histories. The moment where a teacher like Ms. Decker wrote a letter to the student body, showing students how they are never alone, and still delivering tribune staffer’s their favorite foods on their birthdays? She made history.

History doesn’t have specific criteria anymore; this world showed us so; it’s almost as if we started over painfully during the most uncertainty. No longer are the people who write history old white men with no worldview; everyone has a story. We all document it somehow, whether it be Instagram, a blog, or even a journal. In this world, seeing a human outside IRL is a historic feat. This graduation ceremony alone is a historical feat.

It doesn’t matter what race you are. What your citizenship status is. Where you come from. What you have been through. What physical or emotional scars you have.Who you are. Who you love. Wildcats are empathetic, resilient, conditioned to write their own stories and give others a platform. No wildcat needs a stereotypical high school experience. Wildcats not only know how to make history; they are trained how to write it, whether it be on YouTube, Tiktok, in a medical office, in public service, in a restaurant, in a newsroom, on a casting set, on a stage, in a classroom, the list goes on. Wildcats are making history right now.

We are living history; we are all living in a navy-colored hall of fame. Congratulations, class of 2021. We made it; go teach others how to fearlessly and breathlessly make history. Thank you.”

I think I’ve left my mark, I’m signing off.

With love,

Daniela Wise-Rojas (formerly Daniela Wise)

Wildcat Tribune Social Media Manager, Media Leadership ‘21

Dougherty Valley High ‘21

Cornell University, College of Arts & Sciences ‘25

Note: If you would like to reach out to me and just make a connection about anything I wrote about, or are struggling with anything I wrote about and want to talk, send me an email at [email protected]. 🙂