Online learning heightens learning gaps across the school district

School librarian, Allison Hussenet, looks through books ready for curbside pickup as part of the library’s ongoing efforts to keep remote learners reading.

April 1, 2021

The SRVUSD Board of Education presented evidence of significant learning loss among students on Jan. 12, an issue that school staff are now working to solve.

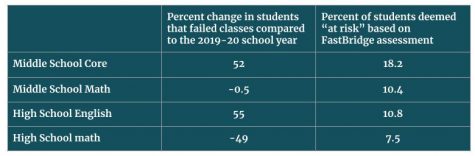

Compared to the first semester of the 2019-2020 school year, there was a 51% increase in the number of middle school students that failed English and a 0.5% decrease in middle school students that failed math. There was a 55% increase in high school students that failed English and a 49% decrease in high school students that failed math.

These numbers were not projected by the district. Curriculum Leader Debrah Petish said, “I was surprised that math grades got better and I was surprised that English got that much worse.” The decrease in students failing math was also out of line with national trends. Petish said that there is no definitive answer for what is causing these discrepancies because of the many factors at play.

The decrease in students failing math was also not uniform across different levels. Algebra One and AP Calculus BC teacher Kellie Judson said that in her calculus class, the numbers held steady and in her algebra class, there were more students who failed math than in a usual year. She also noted that she had more students doing “nothing at all” for her class than usual. Petish and Judson both emphasized that for many students, online school makes it easier for them to learn, which could help explain these numbers.

Another possible reason math grades have improved is that online school makes cheating much easier, but the district’s Director of Instruction, Christopher George, and Petish are both hesitant to place all of the blame on it. “I think a lot of people go to cheating and it could be. It could be that teachers are being far more flexible, as they should be, in a pandemic. It could be a lot of things,” George said.

George also said that during staff development, “we will be discussing cheating…part of the answer is how do we change the way we assess students so they can’t cheat.” He noted that on a multiple choice test, cheating is easier, but a one-on-one conference, where a problem has to be worked through verbally, is more secure.

Judson also explained that students are unable to cheat effectively if they do not have some level of understanding about the concept, so cheating cannot help all students avoid failing their math classes. She also said that her AP students are less likely to cheat because they have the AP test in mind, which they must be able to do well on without cheating.

Petish noted that because of academic dishonesty, as well as points given for completion or participation, grades are not always accurate reflections of what students know, so the district was unsure of how many students will be going into their next math and English classes unprepared. Thus, to get more information about these gaps, the district introduced FastBridge assessments at the beginning of the school year. The same board meeting presented the data: for middle school, 18.2% of students are at risk for English language arts, while 10.4% of students for math. In high schools, it’s 10.8% for ELA and 7.5% for math. Students deemed at risk are those who are unlikely to meet learning goals for the coming year.

These overall statistics are not particularly useful because there are no prior figures to compare them to. CAASPP testing, however, will give information that can be compared with prior years. The district hopes to administer them this semester, but the decision is the state’s to make and they have not given clear guidance thus far.

The more significant purpose of the FastBridge tests is “for the individual teacher to look and say ‘oh this student doesn’t understand operations so therefore we have to intervene and give her support in that specific area,’” Petish explained.

Judson, however, said that teachers were not trained in how to analyze the data about her students, so it hasn’t been particularly helpful. “It’s possible that I could jump on to the website and try and dissect that, but with the amount that I’m doing to maintain my students’ level in class, I haven’t had the time to do that”.

The main way that the district works to support students is the multi-level support system. Every student is assigned to a tier of support based on how much intervention they need to succeed. Petish is working closely with this system, making sure that the district is “working with our site leadership in creating some kind of robust support at the site level, because we really believe that during the school year, your teachers know your learning and your progression better than I do at the district.”

Judson echoed this idea, saying that support is much more site specific and geared towards specific students. She explained that the first step is identifying if a student is struggling in just one class or several, as those warrant different types of support. The initial intervention effort is reaching out to students, parents and counselors. The next level is to bring additional support outside of class time by having them come in during Student Support or work with student tutors.

The district is also looking to summer school as an additional intervention measure for students heavily impacted by online learning, but they have not determined what that will look like. It largely depends on the state of the pandemic and guidance from the state.

Another way that the district is working to address these learning gaps is by training school staff via professional development and training.

Much of this recent professional development is directed towards assessment reform, which the district presented as a way to prevent learning loss. George is working with teachers to discern how to grade students in a way that is “accurate, bias resistant and drives student learning.”

George emphasized that these conversations have been happening for several years now, especially with the formation of the Grading Reform Committee. Judson says that teachers actively seeking out ways to reform their grading systems may have been in these conversations, but full staff meetings about assessment reform started in February and most teachers are still in the initial stages of simply questioning if their grades are accurate. Judson explained that any concrete changes that come from these conversations will only surface next year or later.

The issues in traditional grading have only been exacerbated by the pandemic “If they [grades] were inaccurate before then they’re more inaccurate now. If they were demotivational before, if they were inequitable before, they’re only worse now,” George explained.

One of the issues worsened by the pandemic is inequities among different student demographics. The district’s Equity Coordinator, Ashley Gutierrez, said that because these issues were present before the pandemic, solutions should work to address them overall, not just in this specific moment.

“I think it’s important that when we’re trying to figure out how to support students, we’re looking really critically at our practices and thinking about all of the different reasons that a student might be struggling and come up with an intervention plan that meets all those needs.”

Petish and George both also emphasized that they are cognisant of how difficult these times have been for students and teachers. “Teachers have had to relearn everything in a short amount of time. And we don’t want to neglect that they’ve also had to relearn how to assess how kids are doing,” George said.

Petish echoed the same sentiment, saying that “I think that we have excellent staff, very motivated students and a parent community that is very involved.”

Judson also emphasized that “I think that everyone is doing the best that they can with the hand that they have been dealt at this point in time. I think that’s true of the teachers, administrators, the counselors, the district office and the students.”