Performative activism rises as traditional activism becomes a trend for social media

Modern-day protesting takes a turn as a new group of performative activists branch off from traditional activism’s past.

November 3, 2020

As an increasing number of Americans have begun to spread awareness about the injustices of our country, there has arisen a new group who has learned to capitalize on this “trend”: performative activists.

The meaning of performative activism has changed over the years, from its first use in the 20th century to the modern-day.

The term was first used to categorize a type of activism that relied on using performance arts to convey a certain message. A prime example of this is its use in describing the actions of the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp in 2015, which had protested against the use of nuclear weapons by wielding many decorative posters and banners and dancing in forbidden or traffic-ridden areas.

The activists of today have thrown away this interpretation of activism, as they have not only reverted back to traditional boycotts and protests, but taken dire measures such as looting stores and fighting back against the police (in large part due to their brethren’s role in the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor).

An important factor of the changes to modern-day activism is the use of social media. Leading figures of civil rights movements, such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Susan B. Anthony, had to be knowledgeable to organize wide-scale boycotts and protests, and educate the general public of societal issues. Today’s activists can hide behind the persona of an anonymous account to promote a cause, that they could be uneducated about, with a simple click of a button. This may seem like a minuscule action in itself, but the large communication network that the internet provides allows some posts to be shared thousands of times and viewed by millions, achieving mainstream popularity.

An example of one of these movements is #BlackLivesMatter, which has spurred nationwide attention that has perpetuated the rise of false activism. The Pew Research Center finds that on Twitter, “the hashtag has been used nearly 30 million times – an average of 17,002 times per day.”

From this popularity comes a new definition of performance activism that replaces the original term.

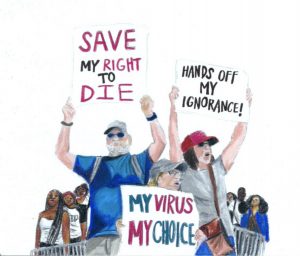

Performance activism is now defined as a phenomenon that draws on the success that traditional activists have received in order to further oneself in a short period of time. The key difference is unlike true activists, performative activists do not practice what they preach; they ironically do not educate themselves about the issues that they share while trying to educate others all the same.

While the motive behind opening these activism accounts is shallow, there is a disagreement about the effects left by them. Many believe that any activism is good as long as it still spreads awareness, regardless of a person’s education on the issue. The general opinion, however, is that activism is not a trend to capitalize on.

Hunter Griffith, a writer for University Star, explains potential harms of performance activism, “Each instance of misguided or selfish use of political struggle ultimately takes space and attention away from those fighting for real change and furthers the idea that being recognized for one’s intentions is what’s most important, and it is harmful.”

Furthermore, performative acts are seen as damning to the trust behind social media as a whole.

“The fluidity with which ideas are attached to and discarded has produced a context of shifting and obscuring meaning . . . Performance is not only an incredibly ineffective way to communicate a lasting sentiment or idea, but it also severely limits one’s capacity to discern whether the ideas and gestures of others are genuine,” Griffith says.

It’s now become a matter of a choice: whether to allow the success of activism to focus on the movement or around the activist themself.

Griffith draws the line between the courses of action that activists should take, as “it is one’s duty to do something by providing material support for those in need or do nothing if one seeks only to use the movement as a means of acquiring social credit.”