Striving for ethicality in an unethical world

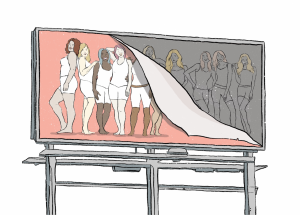

People struggle to use ethical judgement to defy norms of an unethical world.

May 28, 2020

A little over a year ago, I decided to go vegetarian. I’ll admit: it was really hard. Not only did I miss meat (and still do sometimes), but coming from a family that ate meat every day, I had to deal with the reactions of my friends and family, ranging from puzzled to critical. But perhaps the most frustrating part about this past year without meat has been my conversations with others, when I make the case for them to do the same.

The conversations usually go a little something like this: I bring up the topic of meat and we spar about the arguments justifying meat consumption (if you’re interested, some quick and easy resources that influenced my thinking were Kavin’s article about meat as well as this Crash Course Philosophy video—highly recommend!). Eventually, we get to a point where they agree with me that eating meat is unethical. But here’s the catch: “Honestly, I just can’t give up meat,” they’ll say, talking about the bacon, steak, or hamburgers too delicious to forgo. When I press them more on the topic, the conversation usually awkwardly fizzles out, ending with a halfhearted pledge that maybe, they’ll try eating less meat.

This is something that I’ve noticed beyond the context of meat. I encountered a similar sentiment when writing an article for the Tribune last year about disavowing artists accused of sexual assault, where people I talked to continued to listen to such artists without engaging with the arguments I made. This trickles down to our most everyday actions, like the success of fast fashion companies despite the well-publicized environmental and ethical wrongs they perpetuate.

As a quick disclaimer, while I’ll use my personal opinion on issues such as vegetarianism as a vehicle to provide examples and frame my argument, I’m not trying to pass judgement on these issues in this article. I don’t want to get caught in the weeds of what’s ethical or unethical, since that’s subjective (and way beyond the scope of one article). Rather, the core of my argument is why people choose not to act on their ethical judgements, not what those ethical judgements are to begin with.

A primary justification for inaction on ethical issues is the lack of difference a single person can make. Especially in the context of capitalism and the actions of corporations we cannot directly control, the depressing reality is that the impact of our individual choices is somewhat limited. However, many steps of progress in our society, whether it’s the end of slavery or women’s suffrage, also seemed nearly impossible at first. Every collective movement in history has been possible only because of a sum of individual choices. Thus, individually opting out of ethical choices because you believe a movement will fail is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Additionally, we should view the results of our actions not in the context of the entire world, but simply as they are. For instance, a single person going vegetarian still alleviates hundreds of animals’ suffering that they would’ve consumed in their lifetime, even if the global meat industry doesn’t collapse. When viewed in a vacuum instead of held to an near-impossible standard of worldwide impact, that result is still quite admirable. Overall, an action doesn’t need to have earth-shattering implications in order to be the right thing to do.

Perhaps the most common line of reasoning I’ve heard is that it’s impossible to be entirely ethical. People often question whether acting on our ethics leads us down a slippery slope where we notice ethical wrongs in all parts of our lives, yet can’t even come close to righting all of them. Just existing in a capitalist system that prioritizes profit above all else is probably unethical in some way. The clothes I’m wearing and the laptop I’m typing these words on undoubtedly have some negative human cost associated with them, given the exploitative labor practices of most major companies.

Even simple ethical decisions become highly complex dilemmas upon further reflection. Take vegetarianism, for example. I refuse to eat animals mainly because I think it inflicts unnecessary suffering on other living things, but going vegetarian hurts those who depend on animal agriculture for their livelihood. Even if I solely eat plants, the agriculture industry has caused environmental degradation as well and often depends on exploiting cheap labor. And, one of the hardest parts about going vegetarian for me has been my disconnect from an integral part of my Chinese culture: food. My ancestors didn’t have the privilege to eat meat regularly and my family came to America for a better life—part of that being the ability to view food and meat as an expectation, not a luxury. Is there not a degree of ethical wrong in rejecting their sacrifice and hard work, right in front of their faces?

It’s easy to get overwhelmed by the complexity of it all. The more you think about it, the more ethical and moral quandaries will present themselves in your everyday life, none of which have an easy solution. And speaking from personal experience, it can be mentally exhausting to constantly contemplate right and wrong.

However, it’s not productive to simply throw in the towel and live ignorant of our choices. On the most fundamental level, an unethical action doesn’t suddenly become right just because we could do better in other respects. More often than not, I find that this line of reasoning is used as a crutch to assuage one’s guilt at not acting on ethical wrongs they recognize. The sheer scale of problems in our world should inspire us to fight even harder for a better and more ethical future, rather than giving us an excuse to turn a blind eye. So, in the case of the clothes and laptop, while it’s impossible to buy absolutely ethical versions of these products all the time, the approach I’ve adopted is to research the track records of brands I buy from and find better alternatives, as well as perhaps buying less to begin with.

And, if you conclude after doing research that your behavior has been unethical, it’s absolutely okay to acknowledge that! For over 16 years of my life, I ate meat every day without a second thought. Even after I was initially questioned about it, I laughed it off and exhibited the same stubbornness that spurred me to write this article. It took me five to six months to actually make the switch. When I wrote the article about boycotting musicians who are sexual predators, I didn’t even realize that I listened to one such artist until a friend pointed it out. Somewhere down the line, I’ll definitely discover new aspects in my life in which I believe I could do much better. But this isn’t something to be ashamed of. What’s important is not that we’re always perfect down to the very last detail, but that we’re open to questioning our assumptions about the world, admitting that we may not have considered the whole story and acting on the conclusions we reach. We all have done wrong in the past, but that doesn’t preclude us from doing better in the future. It’s all about having forgiveness for ourselves and being willing to grow.

If there’s anything that I’ve learned over these past few years, it’s that to live ethically in an unethical world, the only thing I can really do is be willing to grapple with the tough questions and take action on the answers I find. With respect to the sheer scope of problems our world faces, I think it’s productive to examine the immediate changes we can control rather than being overwhelmed by the big picture. Collectively, we should all consider how our actions, big or small, affect more than ourselves. If you reach the conclusion that something is unethical, don’t just sit on that knowledge—act on it.

This is undoubtedly difficult; the “right” thing is usually not what’s easy, and in the short-term, you don’t get much in return except this fuzzy, abstract feeling that you did the “right thing.” But, while the result will not be that you are perfectly ethical, you will at least be more so. And, it will result in a better world, even if you don’t observe it firsthand. Although I have my opinions, my goal in this article is not to argue about whether specific issues are and are not ethical—that’s up to you to decide. What’s truly unethical is to ignore these dilemmas altogether.

As a final note, I am eternally grateful to the Tribune in part because as I learned to criticize the world’s injustices and hold people in power accountable through writing, I learned to do the same to myself. And along the way, the Tribune has given me an amazing community. People often say that the best friends are those who stand by you unconditionally, but I disagree. The Tribune has given me friends that support me, laugh with me, cry with me and perhaps most importantly, let me know when they think I’m wrong. Over these past few years, the Tribune has given me the tools and support system to think critically and demand accountability from others and myself. As I leave high school behind, I urge you to find for yourself what the Tribune was for me, whatever it is.

Linda Wu • May 28, 2020 at 11:10 pm

Amazing article!! I love the complexity it analyzes.

Ada Zhong • May 28, 2020 at 11:08 pm

So well written!