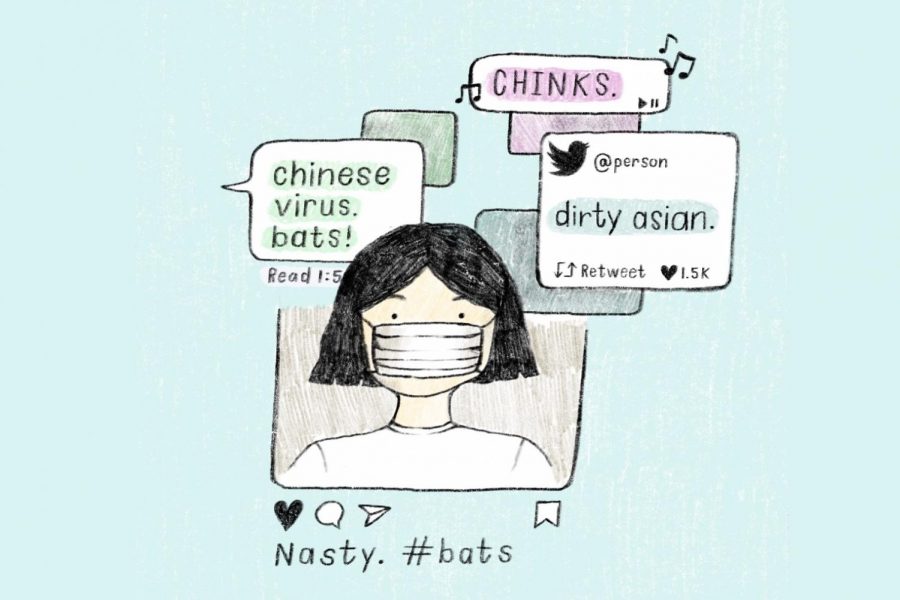

From xenophobia and racism a new virus is born

From social media to real life, Asians have faced severely harmful prejudice related to COVID-19.

May 3, 2020

“A guy came behind me, and as I turned around, he started spraying me with Lysol and calling me all sorts of names.”

“An older white man pushed my 7-year-old daughter off of her bike and yelled at my husband to ‘take your hybrid kids home because they’re making everyone sick.’”

These are just two among 1,135 anonymous reports compiled by the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council, telling the stories of Asians who have been harassed verbally and physically in the past few weeks. COVID-19 has proven not to discriminate based upon race, but it seems that people do.

Fear-based racism and xenophobia toward Asians is not a temporary attitude brought on by the arrival of COVID-19. The birth of Western xenophobia can be traced to the arrival of Chinese railroad workers in the Americas during the mid-19th century.

In the article “Yellow Peril” by Carrianne Leung and Dr. Jian Guan, the two explore some of the earliest evidence of discrimination toward Asian immigrants during that time. They found that Vancouver Chinatown was referred to as “an ulcer — lodged like a piece of wood in the tissues of the human body, which unless treated must cause disease in the places around it and ultimately the whole body.” Language like this prompted repeated “sanitation reform” interventions, which were actually “containment campaigns” aimed at suppressing the influence of Chinese culture on the native Canadian population.

But that was the 19th century. Times have changed, right? What occurred during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak of 2003 would indicate otherwise. That March, SARS was identified in Asia and quickly spread across the globe over the course of six months. Asians faced extensive prejudice and animosity, primarily in North America.

Leung and Guan’s article highlights how Canadian newspapers repeatedly used photos of Asian subjects wearing masks in their stories, legitimizing and intensifying public fear of Asian immigrants and disease. In fact, the article reports that out of 120 total SARS-related photos in the National Post, 50% of them were of Asians wearing masks. Anti-Asian rhetoric during SARS also caused a steep decline in business at Asian restaurants. In a Washington Post article, author Jenn Fang recalls how Pacific Mall, an indoor Asian marketplace in Toronto, became a ghost town during the SARS outbreak. Asian stores lost around 80% of their annual revenue in 2003, a similar statistic to what Asian businesses began to experience during the initial outbreak of COVID-19.

Although it has been 17 years since SARS and almost two centuries since the initial arrival of Chinese immigrants in North America, it seems as though anti-Asian rhetoric has barely aged. We are seeing the same story play out again, yet this time, popular culture and social media provide a new outlet for racism to flourish.

In a recent post on Instagram, an account by the name @antiasiansclubnyc wrote, “Tomorrow, my guys and I will take the f*cking guns and shoot at every Asian we meet in Chinatown, that’s the only way we can destroy the epidemic of coronavirus.” The same account went on to write, “Please do not take this negatively, we are trying to help our planet.”

The account has since been taken down, but racist tropes and hostility do not just exist on just one social media platform. On Twitter, rapper Lil Reese tweeted that Chinese people are “nasty” and that they “got the whole world f*cked up.” The tweet has dozens of thousands of likes and shares, not only displaying the compelling ability of social media to spread problematic messages to a massive audience, but also showing us that Lil Reese is only one of thousands of people with the same thoughts.

Although these are the more obvious instances of racism, there is content on social media that may not strike you as “racist” or “xenophobic” when they still are. Whether it a simple joke or a more subtle expression of discrimination, these implicit forms of anti-Asian rhetoric in the media are just as harmful.

In an informational Instagram post from UC Berkeley’s Health Center, the college identified a set of “normal” reactions that people might have in response to the virus. Among the reactions on the list from the health center was “xenophobia: fears about interacting with those who might be from Asia and guilt about those feelings.” This unacceptably suggests that it is justifiable to use the crisis as reason for racism.

In a new song titled “Spreadin’ (Coronavirus),” artist Psychs raps about trying not to catch the virus. In a specific verse of the song, Psychs sings “And corona was not a surprise, why? ‘Cause everything’s made in China,” implying that China should always be the first to blame no matter the circumstances. Not only does the music video for the song have 31,000 likes on YouTube, but it has also gained popularity on TikTok, with all kinds of people dancing along to the lyrics.

At first glance, these two examples may seem harmless, especially in comparison to more hostile remarks. However, no matter how severe it is, racism leaves its mark.

In fact, these types of cases are just as bad because they normalize discrimination and use social media and pop culture to disguise hidden hate and hostility they hold. When people see memes or posts that feature anti-Asian rhetoric and brush them off as “just jokes,” they tacitly endorse the underlying notion that Asians are to blame for COVID-19. Whether people realize it or not, these seemingly harmless behaviors can quickly manifest into real hate and violence.

Many people defend these posts, claiming that they are meant to be comedic and not taken seriously, which could help lighten the seriousness of the current situation and relieve some common feelings of anxiety. After people started calling out racist messages on an Asian woman’s TikTok, the confronted users claimed that they were only joking.

Though it may be true that some jokes and memes are not made with malicious intent, the negative impact remains. Continuing to allow these memes and jokes only facilitates the spread of racist ideas and reinforces the notion that racism is not harmful.

Even if online activity doesn’t directly cause hostility, the influence it has on people’s opinions and ideas can translate into real-life altercations. As Leung and Guan explain, when “media sensationalism and panic have been rationalized,” they become “justified.” Receiving justification online is what leads to action in real life. People become less afraid of the consequences when they believe actions that are unacceptable have good reason behind them.

This is why we see more than 1,000 accounts of in-person attacks against Asians recorded by the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council. Spurred by the internet, fear has become justified.

Yet this hate does not come without resistance. Tags such as #HateIsAVirus are spreading a more positive message. Michelle Hanabusa, founder of Uprisers — a community-based fashion brand in Los Angeles — has been promoting social awareness and representation for the Asian-American community in various ways. In late February, Hanabusa reached out to BetterBrave and AsianHustleNetwork and started the movement #HateIsAVirus to combat anti-Asian prejudice arising from the pandemic.

“People sharing their stories, writing #HateIsAVirus on their masks, or wearing a T-shirt is the way for us to spread awareness of what’s going on in our community. My friends who are outside of the Asian-American bubble, their algorithms are different on Instagram or Facebook; they don’t see anything about racism and xenophobia,” Hanabusa explained. “So, that gave me the clear indication that we need to hit people outside of our circle and create change through social media.”

Hanabusa hopes that others will follow in using social media to promote positivity and awareness rather than insensitivity. The official Instagram page, @hateisavirus, has over 3,800 followers as of today and has received support from influencers such as Steven Chen from BuzzFeed and renowned TV broadcaster Adrienne Lawrence. Additionally, #HateIsAVirus set up a GoFundMe page where almost $4,000 has been raised to help support small businesses run by Asian-Americans.

Hanabusa said, “There are so many people who are not even Asian who are really supporting this movement now, and I think that a lot of minorities can relate to it. I’m even talking to my lawyers right now to turn this into a nonprofit.”

Instead of using the internet to spread negativity, Hanabusa urges everyone to use technology to “pivot to help a community or cause.”

“We want everyone to spread this awareness with compassion. That’s the type of energy we need to create positive change — it’s not through rage. There’s different ways to partake and we want people to know that we’re here, we’re listening and we’re not alone.”

The internet can be a dark place, but it does not have to be. #HateIsAVirus and many other social media movements are proving that to be true. There are countless ways to use the internet for good, whether it be something as simple as resharing a positive post you come across or following the pages that are aimed at spreading awareness — it all counts.

We can also use the internet to promote other supportive ideas such as ordering takeout from local Asian-owned restaurants, joining virtual events aimed at fundraising for coronavirus relief efforts and Asian-owned businesses, and donating directly to organizations such as #HateIsAVirus to show solidarity toward the Asian community.

Regardless of our efforts, it is important to realize that change will be gradual. Shifting attitudes ingrained in American society for centuries is not going to happen overnight, and that is okay. But little by little, our efforts will add up, which is why we need to stay dedicated to the cause, and why we need to take advantage of the powerful tool that is the internet to provide the Asian community the representation it deserves.