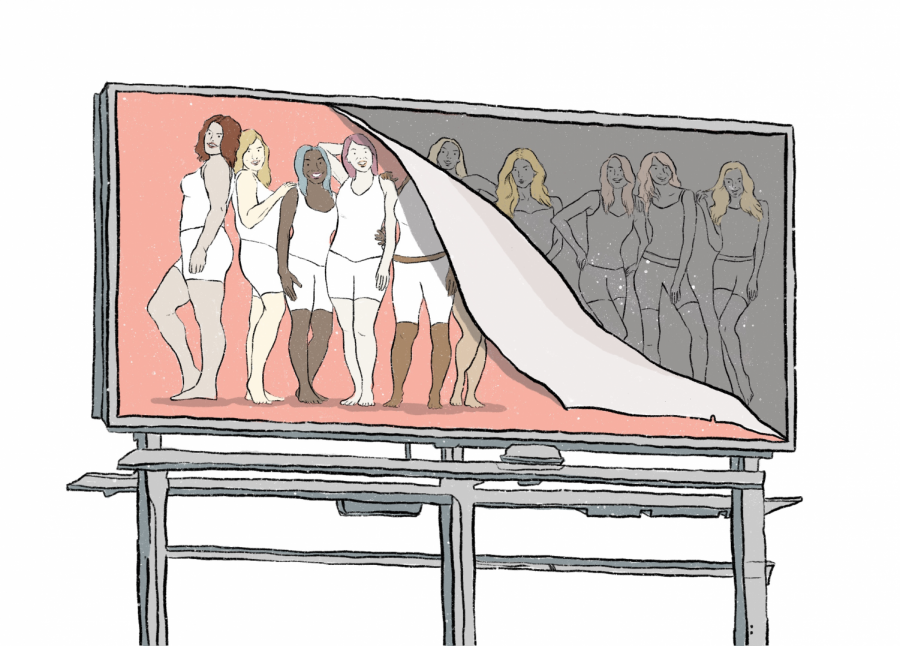

The illusion of inclusive marketing

The illusion of inclusivity marketing hides a history of corporate deceit.

December 1, 2019

Dear Reader,

There’s this one store in the San Ramon City Center that I’ve told all of my friends about. It’s this impossibly stylish clothing store, owned by an ex-supermodel, with a meticulously curated designer collection targeting the strata of women who would consider a $1,000 white cotton frock a “steal.” Occasionally, for fun, I’ll wander into that store and run my fingers along the clothing racks, like I’ve seen Emily Blunt’s character do in “The Devil Wears Prada,” feeling uber-chic in the process. Of course, I can’t actually buy anything.

High fashion — a phenomenon conceived in 19th-century Europe to elevate specific forms of fashion to the status of art — has always relied on its exclusivity as its biggest selling point. To be considered as high-fashion, fashion houses must have an atelier in Paris with at least 15 employees, present two collections a year at fashion shows and design (necessarily expensive) personalized pieces for clients, among other stringent requirements. While catering to rail-thin, lithe, and at least 5-foot-9 women was perhaps not its intended purpose, modern high fashion has comfortably occupied that niche.

But in 2019, a year in which fashion and beauty companies are increasingly coming under fire for their relentless exclusivity, corporate America has decided to break away from that narrative through a series of inclusive marketing campaigns intended to make us normal people feel like we too can rock that $2,500 zebra-print fanny pack. As campaign after campaign surfaces with “real,” “diverse” people representing previously inaccessible brands, Twitter lauds the companies for their transition to ‘wokeness.’

Which is all well and good. Except that by themselves, these inclusive marketing campaigns are just that: marketing. Far too often, corporations use these campaigns as a stand-in for true ethicality, without actually instituting social change from within.

In 2018, Everlane, an American clothing retailer that aims to democratize high-fashion and prides itself on its “radical transparency,” released an inclusive marketing campaign featuring a plus-sized model wearing the brand’s signature underwear line. While the campaign was praised for signaling social progress within the fashion industry, no one seemed to notice that Everlane hadn’t even released a plus-size underwear line in the first place. The campaign, while relevant and cool, was a sham. This sort of insincerity, when a corporation is able to appease consumers by only presenting an image of inclusivity, is not criticized nearly enough.

In a way, it is understandable why we want to buy into inclusive marketing campaigns so badly. It’s undoubtedly hard, if not impossible, to be a completely ethical consumer, so when companies run campaigns with buzzwords like “diverse,” “inclusive,” “flaws” and “feminism,” it’s often tempting to just buy the damn thing.

But being steadfastly uncritical of such glaringly clumsy campaigns halts true progress from within. Corporations are given a free pass to continue unethical practices under the guise of “inclusivity.”

Pamela Bump, a journalist who’s contributed to the Harvard Business Review, recently wrote a blog on HubSpot detailing “7 Brands That Got Inclusive Marketing Right,” which featured Proctor & Gamble as its top pick. Proctor & Gamble, a company which owns Dove, Tide and Gillette, recently ran an inclusive campaign that followed several African-American mothers over time preparing their children for racism in the world. The ad was wonderful, poignant and highly-acclaimed. But at the same time they released the ad, Proctor & Gamble was simultaneously conducting unethical animal testing in their facilities and using child-labor to manufacture some of their beauty products. This split between the company’s projected values and the realities of their inner workings was deeply disturbing. But online, the overwhelming praise the company received for their “inclusivity” drowned out criticism of their other human rights infractions.

#Inclusivity is trending and corporations have eagerly latched on.

The free pass of inclusivity marketing has become so prevalent that corporations seeking to hop on the trend are running campaigns with all the relevant buzzwords while not having an actionable message. For another Proctor & Gamble ad campaign, this time for Dove, the company set up pairs of doors in various cities around the world with one door labelled “beautiful” and the other labelled “average.” The ad followed diverse women as they chose which door to walk through, with the most common choice being the “average” door. The ad was clever, but the only solution to female self-hate it offered was buying more Dove products.

As journalist Amanda Mull noted in a Vox article, “…simply identifying the problem would get Dove full credit and move plenty of product, but the urge to talk about a broad cultural problem while refusing to name a bad actor left the blame squarely on the shoulders of the women who had the temerity not to love themselves sufficiently.”

I admit that my knowledge of advertising comes primarily from the TV show Mad Men, but the Dove campaign is a classic case of a glittering generalities advertising strategy: comes asymptotically close to real cultural criticism but ultimately settles in reveling in its own “edginess” without actually doing anything.

It’s not enough to point out problems in consumer culture or demonstrate understanding of them; there must be tangible change.

I’d like to clarify that I fully support inclusivity in consumer culture. It’s high time that high fashion sheds its elitism and begins to welcome all people into the fold. And I do believe that a key part of creating a more inclusive consumer culture involves inclusive media campaigns. The damaging effects of unrealistic media campaigns in fashion on young people has been extensively documented and must be changed. However, what I’m saying is that inclusivity is not campaign-deep. Featuring a token person of color in an inclusivity campaign does not justify a fashion company’s continued usage of primarily thin, white models on the runway, for example. And unless we realize this, refuse to acquiesce and demand more from corporations, we will not achieve true inclusivity.

So I’m asking you, dear reader, to be critical of the “inclusive” marketing campaigns you see all around you. Really evaluate whether the message of the campaign and the history of the corporation make sense or if they’re just co-opting social movements and language for sales.

I get that it can be hard to be a constantly vigilant and ethical consumer. Sometimes you’ll see a really cute pair of pants or a charming ad and you won’t care about what it all means. I get it. But as long as you’re willing to overlook corporate deceit, it’ll self-perpetuate.

So, if you see a trite “inclusive” campaign which means absolutely nothing, roll your eyes and call it the f**ck out.

Sincerely,

Sraavya