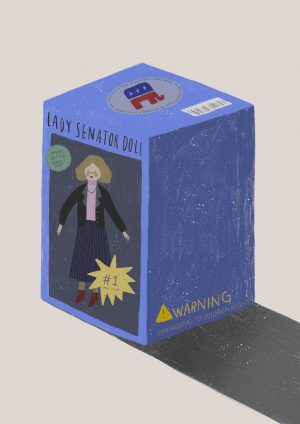

Periods, pills and pre-existing conditions: separating the stigma from birth control

April 30, 2019

The invention of birth control has historically been hailed as a catalyst for women’s rights and the freedom for women to plan out the course of their lives.

According to Mrs. Rebecca Uscian, English and former Social Justice teacher, “It gave women an option to choose when they can start a family. And that’s so important. We should have the option to decide that ‘I don’t want to start a family until I’ve established myself in my career field’ … It gave women access to plan their families to match up with their beliefs.”

And while birth control has this history, our modern conversation about birth control is quiet and filled with misunderstandings, which give rise to stigmas that surround the women who take it, and the medication itself.

In order to revitalize the conversation around birth control and remove the misconceptions around taking it, below are stories from real women who are taking or have taken birth control, revealing the realities of women’s health.

First, what is birth control?

According to WebMD, birth control is defined as “any method used to prevent pregnancy.” While this is still technically true, modern birth control has evolved into a variety of different forms that can serve health purposes beyond the commonly stated, becoming a common topic in the conversation about women’s health.

The most obvious and perhaps most common form of birth control is the birth control pill. This is the method typically mentioned during the conversation about birth control: a 28-day pack with three rows of seven pink “active pills” and likely a row of placebo ones.

Introduced in 1950 by Margaret Sanger, a fierce advocate for birth control, this method was also the first medically backed hormonal birth control.

The birth control pill works to prevent pregnancy in a couple of different ways. The combination pill, referring to the birth control pill that contains both a dose of estrogen and progestin, work by preventing ovulation — when the ovaries release an egg — so there is nothing for sperm to fertilize. Different pills contain different amounts of these hormones; according to Medical News Today, “doctors rarely prescribe high-dose combination pills because the low-dose pills work just as well and cause fewer side effects.”

The combination pill also thickens the cervical mucus and thins the lining of the uterus. This makes it harder for sperm to navigate through the cervix and decreases the likelihood of implantation, in the chance that an egg is fertilized. These latter two effects are due to the hormone progestin in the combination pill.

There is also another form of the pill called the “minipill,” a progestin-only pill, that also produces these effects but doesn’t prevent ovulation.

When used perfectly, the combination pill is 99 percent effective — 91 percent with typical use, which encompasses the times when people forget to take it or take it at inconsistent times. The minipill has percentages that are just a tad bit lower.

The selection for different types of birth control has expanded since the 1960s — all of them hormonal, with the exception of copper intrauterine devices (IUDs), which are effective 99 percent of the time because, according to Planned Parenthood, the copper invokes an inflammatory reaction that lasts for up to 12 years that is toxic for both sperm and eggs.

The hormonal version of the IUD also sits inside the uterus and releases progestin over the course of a few years, making it another long-term birth control option.

Another long-term birth control option is the implant, a small plastic rod that is inserted into the arm and releases hormones in a similar manner to the IUD. Both the hormonal and non-hormonal IUD and implant have an effectiveness of over 99 percent, and since they are incredibly low-maintenance, there is normally no discrepancy between perfect and typical use.

Other various hormonal birth control include the birth control shot, vaginal ring and patch; these options vary in their duration and effectiveness.

There is no medical evidence that any of these methods impact fertility long-term, and when birth control is removed, the ability to get pregnant should return almost immediately.

What does birth control do?

Birth control is mainly advertised to prevent pregnancy, but the way estrogen and progestin (a form of progesterone) interact with the body means that many girls may start birth control well before they have to worry about potentially becoming a parent.

Naturally existing estrogen and progesterone in the body interact with a woman’s reproductive system and are secreted by the ovaries, which, in turn, can be thought of as the crux of female reproductive health. These hormones are necessary for menstruation, fertility and puberty, so similarly the hormones in birth control can supplement an imbalance occuring in the body, as well as any problems associated with the aforementioned occurrences.

“I didn’t have a period for four months, and I was like, something’s wrong, like very, very wrong,” junior Sierra* commented about why she started taking birth control this year. So I decided to go to my doctor, and they said, ‘I think maybe birth control could really help regulate your period.”

She continued, “I also found out that the reason why I’m on this specific brand was because polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) runs in my family, and apparently this is really good for avoiding PCOS, which I didn’t know about.”

PCOS is a common hormonal disorder that causes enlarged ovaries and the growth of cysts, and is just one of many different diseases associated with the crux of female reproductive health. According to youngwomenshealth.org, birth control falls into the treatment of endometriosis, irregular or heavy periods, menstrual cramps, premenstrual syndrome (PMS), Primary Ovarian Insufficiency (POI), hormone replacement therapy, the prevention of some cancers and even stubborn acne.

Essentially, with most problems that can benefit from the existence of additional hormones, birth control may be prescribed to try to combat that problem.

“I started the birth control pill my freshman year of high school, mainly because I had an extremely heavy flow and bad acne,” senior Monica* said. “My doctor said that [the pill] would eliminate long periods, and because of the estrogen … I would get fewer breakouts.”

“The pills have helped reduce my acne, but the best part is that my period is so much lighter,” Monica*continued. “After starting the pill, I only bleed for three days and it’s light. I skip my period sometimes too, which is nice.”

For people unfamiliar with birth control or who are wary about its hormones, skipping a period may sound unhealthy, but rest assured: according to the National Women’s Health Network, skipping a period is just as safe as having a regular menstrual cycle, given that the woman doesn’t have any underlying medical conditions.

While these benefits are generally applicable to most forms of birth control, the copper IUD in particular can also act as a form of emergency contraception.

What side effects does birth control have?

Of course, like any medication, birth control is not a universal savior of women’s health, in the sense that there are side effects to consider, and it may exacerbate certain medical conditions if family history is unknown.

According to Planned Parenthood, people who have a history of blood clots or an inherited blood-clotting disorder should not use birth control, and it is important to bring this up to the doctor prescribing the medication. Other concerns include a history of breast cancer, heart attacks or other serious heart problems, migraines, uncontrollable high blood pressure or liver disease.

Women also report feeling various side-effects after being on birth control, to various degrees.

“I knew with birth control there were many positive effects like lighter periods, less acne, bigger boobs, but one effect that affected me the most definitely is weight gain,” Monica* commented. “I gained [a lot of] weight on the pill. I don’t think the pill caused it, but it’s harder to lose weight on the pill … I know some people are affected by mood swings; however, when I started birth control, I never really had them.”

“My biggest thing is nausea,” Sierra* described. “My first two months I always threw up and I got really emotional. I think one time I cried so hard when I was watching ‘Meet the Robinsons’ and my boyfriend asked, ‘Are you … okay?’ and I said, ‘I think I am.’”

Intermenstrual spotting is also a common side effect, especially in the first three months on the combination pill when the body is getting used to the adjusted hormones.

The medical informational guide that also comes with the birth control pill also lists a series of possible side effects that may indicate that this particular birth control isn’t right for the user — serious migraines, depression and any other irregular pain are often reasons for people to move off the combination pill and onto the minipill, in cases where the excess estrogen may cause these problems.

“Four or five years ago, I started getting migraines, so now I’m required to be on a special form of the pill called the minipill … because it can increase your risk of stroke,” Diana* said, an adult who began the combination pill when she was 22. “I hate [the minipill], because its not regular and the side effects are unpleasant. And it’s very strict in that you have to take it at the exact same time every day, and if you don’t, it messes with you. But the alternatives really suck, so I don’t know what to do.”

“The combo pill was much better and had very few side effects. [On the mini pill], the spotting is really annoying,” she continued. “I don’t feel as good on it … I get really moody right before [my period], almost as if it were a real period. And that’s the thing with birth control it’s not technically a real period, so you shouldn’t have the same effects. There was a two or three month period when I was off it, and I legitimately did feel better. Unfortunately, I went back to my regular periods, which were miserable, so that’s the trade off.”

With more long term options, such as the hormonal and non-hormonal IUD, as well as the arm implant, side effects differ due to the absence of estrogen, but they have side effects nonetheless. For the copper, non-hormonal IUD in particular, it’s common to have spotting, cramping and heavier periods, but they’re still not an ubiquitous experience. The hormonal IUD also may include the possibility of irregular periods and spotting, but for many women, the horror stories of the pain of inserting the IUD is actually what turns them off from getting it.

“[The insertion process] was horrible, actually. Now I’m really happy that I have it. I don’t regret it at all. I literally passed out twice. They said okay, we’re gonna get you some water and then waited until I was [okay]. And then I passed out again and I threw up. I had to have my sister come pick me up from the appointment,” Hannah* said, an adult who is currently on the hormonal Mirena IUD.

However, she does admit that she also passes out during blood draws, so she feels that she might just be more sensitive to medical procedures. And even with her horrific experience with getting the IUD inserted, she still encourages it as an option for women who would like to consider a long-term option.

“[The insertion process is] just really crampy and horrible. Obviously, it’s an intimate procedure so you’re scared … and even though I had the craziest case scenario, I’m still happy. I love not having to think about it every day and in terms of family planning, I don’t have to worry.”

“I have friends that were totally fine,” Hanna further explained. “They said, ‘I went in and it was inserted, and then I went for a run afterwards, and we were totally fine.’ So I have heard a lot of people that had no issues.”

The arm implant is similar to the hormonal IUD in terms of spotting and irregular periods being the main side effects, and similarly, the main concern is the invasiveness of the procedure to insert the implant.

“I don’t think there’s a good form of birth control out there. There are so many risks associated with it in general: stroke, heart attack etc.” Diana* commented. “There also isn’t a good form that doesn’t have side effects or doesn’t hamper your daily life in some way. ”

What about access?

The average price of uninsured birth control is around $50 per month. Luckily, with most health insurance plans and qualifications for government programs such as Medicaid, the cost of birth control is usually covered. Under the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare), most health insurance plans must also cover doctor’s visits that are related to birth control.

In cases of unemployment, or lack of insurance, however, this means that the costs of birth control pills can add up fast — to about $500 a year. Women can still receive birth control for free or at little cost from nearby medical centers as a college student or Planned Parenthood.

“My birth control from Kaiser is free because I have health insurance. However, if you are under 18 and do not make money, you can go to Planned Parenthood and register under the state of California to receive free or low cost birth control. Planned Parenthood prescribed me a year supply of pills which is awesome,” Monica*says. “My parents know I’m on birth control, but my doctor made it my choice to say whether or not to tell them. They are extremely confidential, especially at Planned Parenthood.”

While in most states, minors are able to acquire birth control from Planned Parenthood without parental permission, different insurance companies and health clinics have different policies of confidentiality that may require parental permission, especially if the minor is covered under the parents’ health insurance.

Because Planned Parenthood has often been in the spotlight for their controversial access to abortions, some women are wary of going there to receive a birth control prescription. However, the institution also provides tests and treatments for many other aspects of women’s health.

“Planned Parenthood gets put under this umbrella of an abortion clinic, but it also does amazing work for underserved women that might not have access to women’s health. Cervical cancer is a huge epidemic among women, and not having access to get regular check-ups is detrimental,” Uscian explained. “If you close [Planned Parenthood] down, you know who still gets check-ups? Wealthy women. You know who doesn’t? Poor women. And so by closing that off, you’re essentially saying, ‘Sorry, but you don’t deserve access to women’s health.’”

Diana* described her own experience with Planned Parenthood during a lapse in her insurance coverage:

“There was a time where I didn’t have any insurance, so I had to go to Planned Parenthood, and they were the nicest people. They were like, ‘Here’s a whole year of pills,’ and, ‘What else do you need?’ When people condemn Planned Parenthood, I just think of how incredibly kind they were when I didn’t have insurance, and didn’t make me feel badly about it, and they understood I had no insurance, no extra money, and they provided me with so much information and resources.’”

Other birth control options, such as the long-term IUD and implant, which requires a medical procedure to insert, cost an average of $1,300 without insurance coverage. However, in Hannah’s* experience with her insurance company, she only had to pay around $100 out of pocket.

What are our attitudes about birth control?

Medically, a birth control prescription falls into the category of “women’s health,” but its obvious connotations carry a lot of weight in the form of stigmas and stereotypes.

“My dad doesn’t know,” Sierra* said. “It’s only between my mom and I, because … there’s a big stigma about it. And, my dad will instantly think, ‘Oh, she’s sexually active!’”

Birth control is used for family planning and preventing pregnancy. But a common perspective is that all women on birth control take it solely for this reason, and that somehow, by taking this medication, they will automatically be associated with sexual promiscuity, or sex in general — an activity that comes with certain responsibillities people may not be comfortable with teenagers taking on.

“A lot of people always assume it’s for sexual reasons … I told some of my guy friends about it, because every month I usually change the time I take it, just to see which is the best time, and one of those times was 10 p.m.,” Sierra* said. “And I’m hanging out with my friends and they said, ‘Why are you taking that?’ and I answered, ‘It’s my birth control.’ And they were just looking at me like ‘[She’s a] slut.’ And I said, ‘Guys, can you not look at me like that?’”

While many women start using the pill because of menstrual problems, hormonal imbalances or any other health issue, women, including teenagers, also do take birth control because they are sexually active. And while everybody’s view of sex may vary, the stigmas that arise from the reality of sexually active teenagers still carry over to the people who use birth control as any other medication.

“There are so many ways birth control can help you, but even if it is for reasons where you don’t want to [get pregnant], why would you shame someone for it?” Sierra* mused. “Some people take it for their periods. Some people take it for sex. Some people need the rationalization that it helps their period. Birth control also helps transgender men. But we also need to remember that there’s still the option of people taking it for being sexually active and we need to be more comfortable accepting that women can be sexually active.”

Ultimately, among the myriad of birth control options and burdens of stigma, Uscian emphasizes the importance of agency when it comes to making decisions about personal health.

“It has to be your choice. You should be informed with your doctor. And you should also make sure that you’re not jumping on something new or a trial, or you want to look at the side effects and consider what those might be,” Uscian said. “Like any drug, you want to make informed decisions and talk to your doctor, and decide what’s right for you.”

*Names changed for privacy reasons