“The End” provides an explosive beginning to AHS “Apocalypse”

October 23, 2018

“I can’t believe we’ve come to this,” a newscaster cries as people swarm the streets and panic runs amok. Nuclear missiles have destroyed Hong Kong and London. The horror hasn’t even started.

With “Apocalypse,” Ryan Murphy and Brad Falchuk craft a masterful opener to the last season of the hit TV show “American Horror Story.” Murphy and Falchuk, no strangers to controversy, have previously critiqued Donald Trump and America’s polarized political landscape.

“AHS: Apocalypse” combines visceral, scary-real horror — horror that could plausibly happen — with the supernatural element that keeps fans in the fold.

This season was well-received by fans who had long awaited extensions to “AHS: Murder House” and “Coven,” two of the most popular seasons. The ending of “Murder House” featured a painstaking cliffhanger with the birth of a child who was rumored by fans to be the Antichrist, a rumor that may play out this season. The finale of “Coven” did not stray away from similar apocalyptic tones. The ending is set to eerie vocals as Cordelia Foxx (Sarah Paulson), the newly appointed supreme witch, welcomes recruits to her school of witchcraft promising to no longer just survive but to thrive. The crossover of these two seasons promises the return of favorite characters and riveting plot lines already engrossing viewers.

AHS’ had promised to welcome back veteran actress Jessica Lange, an interesting development with Lang swearing “Freak Show” (season four) was her last appearance in AHS. Her performances in the early arcs launched the show in critics’ eyes and her role remains a mystery. However, it’s suspected that it has to do with the ‘Antichrist’ from “Murder House,” as she played a key role in creating and caring for the demon baby.

“The End,” the first episode of the season, is a brutal, twisted experiment in utilitarian calculus. Fresh from a college acceptance to UCLA, ironically another brutal selection process, Timothy Campbell’s (Kyle Allen) celebration is cut short by the announcement of an imminent nuclear strike. Government agents break down the door as part of the Cooperative, announcing that Timothy’s genes make him an “ideal candidate to … survive.”

AHS’s horror is always human at its root, and viewers cannot help but feel Timothy’s mother’s (Dina Meyers) anguish as her son is ripped away in a perverse “Sophie’s Choice” scene. She begs for the Cooperative to take her other son, but “the end” is near. Only one can survive the blast. The scene is a direct parallel to just moments before, when a wealthy businessman facing an inevitable doom with his family in Hong Kong calls his entitled, oblivious daughter, begging her to survive within the Cooperative’s clutches. Meanwhile, the streets are crammed with cars driving nowhere, on a futile road. Where will the road take you out of the reaches of a nuclear missile? The mob mentality of the crowd is exposed and society’s darkness is shielded by a thin facade of politeness and order and wealth, like something out of “The Purge.” But it’s human, and that’s where the horror is.

Even within the Cooperative’s secret bunker, “Outpost 3,” implying the existence of further “safe” houses, the first scene a couple is seen on their knees among the radiation-soaked hazy field begging for life – not their life, as Murphy and Falchuk would have us expect, but the chance of life in a world destroyed. “Please, we won’t do it again,” they plead, and though the viewers can sense the inevitability, the firing squads pierce through.

The horror of being deselected is a critique of the opulence of the top 1 percent. In a hidden survival bunker, those not rich enough to pay their way in or not Übermensch-esque enough to score a spot are devolved into “grey,” their lowly status marked by their drab coats. Yet, by the same utilitarian mindset, each member of the bunker receive the same, bland, gelatinous “food cube” with all their needed nutrients.

“The End” is an obvious critique of vanity. Hair, an extended motif, is construed as the epitome of outward appearance – keeping said appearances up even in the face of death. Murphy and Falchuk once again questions our flawed conceptions of a meritocracy – who deserves to live? The ultra-rich, caught up in their pomp and hair, or the genetically superior? Murphy and Falchuk maintain that ability to flawlessly blend modern conflict into the horror genre layering deeper meaning into each scene. The ultra-rich are notably shown as impermeable, their pale ignorance blind even in the face of nuclear bombs. “It’s probably fake news. I’m calling Donald,” a rich old woman cries as her housekeeper runs away, thinking that the troubles of the people will slip away like water on a duck.

Claire Zhang

Claire Zhang

There’s nothing Murphy and Falchuk won’t stray away from. The themes of reproduction and survival of the most fertile, reminiscent of the “Handmaid’s Tale,” are juxtaposed with a gay couple. Murphy, Falchuk and AHS are incredibly inclusive and friendly toward the LGBT community; while not devoid of controversy, one only has to look to the peculiar orgies of “Hotel” and Countess Eli zabeth (Lady Gaga), slitting the throats of transphobic men to prove. But the stark presence and untimely, unfair death of Stu (Chad James Buchanan), a gay character, does not feel like erasure, as in “The 100’s” murder of a popular bisexual character, but rather a cruel critique of our values.

Much like our present world, Murphy and Falchuk presents this twisted meritocracy to expose its underbelly. It’s no coincidence that the inventor of the term “meritocracy,” Michael Young, coined it as dystopian satire, where the elite stratified society into a war on unintelligent people. The irony is that there’s no true merit-based system, as in our world. The utilitarian guarantees, such as that protecting from deadly radiation to ensure the survival of all, are false. Miriam Mead (Kathy Bates) and Wilhelmina Venable (Sarah Paulson) rig the game, killing Stu for the sake of bloodshed.

The show’s disfigured humor questions who exactly is watching the show; “The stew is Stu!” his lover exclaims. Some drop the spoons in disgust, but the rich old woman keeps eating. The indulgence of late capitalism is so rich that it is literally cannibalistic. She keeps pleading ignorance, in the same sort of way people know their iPhones are made with child labor or the shirt a person is wearing is probably made in a sweatshop. It’s clear that our standard of living is unsustainable and its evident that the world is an awful, unfair place. Whether one thinks Murphy and Falchuk commodify this thinking or critique it is a question of one’s own culpability. “It tastes like chicken,” she coldly remarks. After all, with her blinders of privilege on, it’s better than the nutrient cubes. It’s deconstructed scenes like this that give insight into society today that make AHS so unique.

The guests at the table are forced every night to dress up in formal clothes to dinners like this. Society tries to mask the evils, failing with disgusting irony. Pure, revolting horror, an “AHS” special: in the end, we’re left questioning if the real horror is out in the radioactive wasteland or in the bunker.

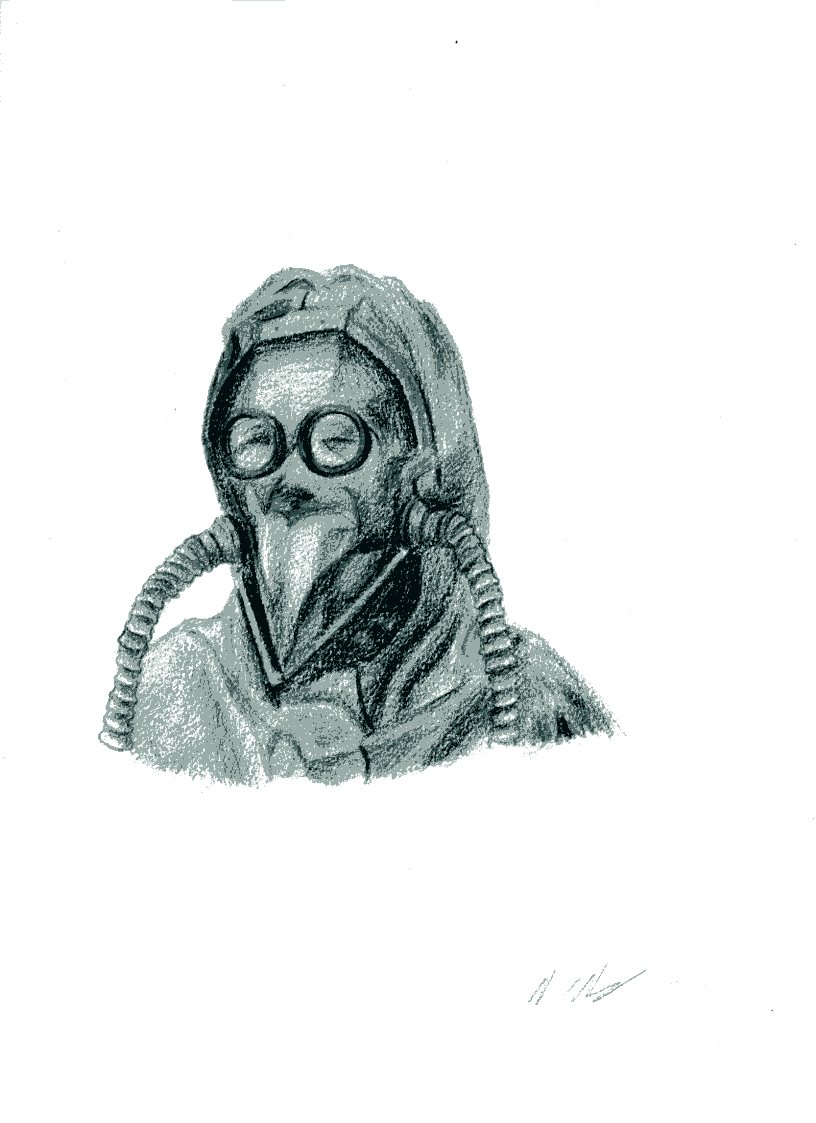

AHS continues its clever commentary with its costume design. Notably, the gas masks everyone wears to protect from the deadly radiation are reminiscent of witch doctor masks. Murphy and Falchuk wants you to know this – we’re living in the Black Plague. There’s no cure, and the witch doctors can only preach cures with an inevitable end. Venable rations food, but what’s the point of rationing if there’s no hope in sight?

The bewitching and supernatural elements to keep horror fans on their toes coupled with thought provoking commentary was warmly welcomed by fans of the previous seasons. “The End” provides a captivating introduction to “Apocalypse” that will keep viewers tuning into the show week after week, caught in a web of their own horror and disgust. Like Miriam Mead opines, “They made you think the system was a rock. It was a water balloon. One prick of the needle” and it’s “apocalypse.”