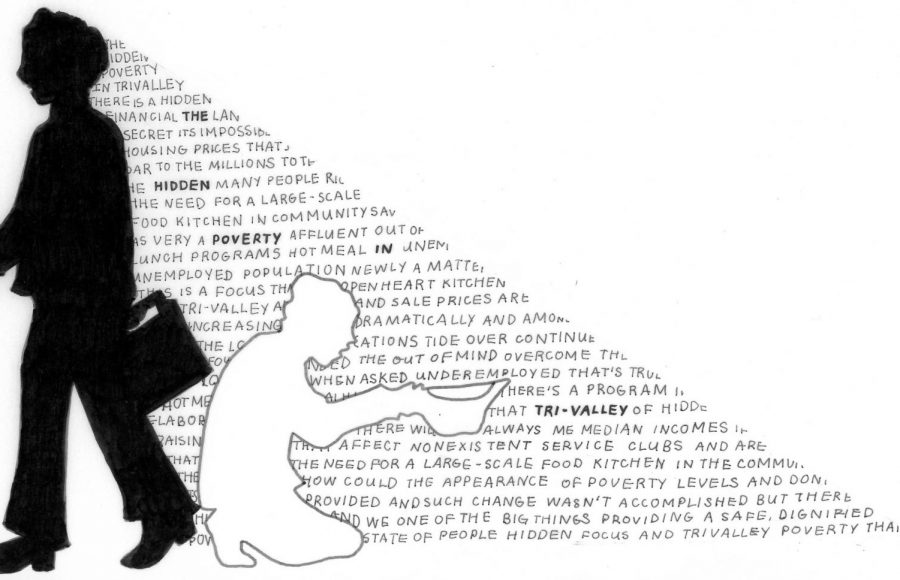

Poverty lurks behind the Tri-Valley’s gilded mask

October 26, 2017

The Tri-Valley, land of median incomes nearing to $130,000 a household, wineries and the not-so-rare occasion when three or more Teslas line up before one stoplight, has a secret.

For many, it’s impossible to believe that poverty of any kind can coexist with housing prices that soar to the millions and people who can afford to buy Coach purses in bulk. Even at Dougherty Valley, a high school where masses queue up to join one of the dozens of service clubs, collection bins for canned food drives remain conspicuously empty.

Among the 102 students surveyed, 85 percent felt that poverty was either nonexistent or barely an issue in the community.

In the same poll, when asked what word came to mind when “San Ramon” was heard, almost 40 percent immediately came up with some form of the words “privileged” or “rich”, with one anonymous individual explaining, “When I think of San Ramon, I think of people with a substantial amount of money. I don’t think of many people having any financial issues. Most in San Ramon can usually buy everything they want and more.”

The need for a large-scale food kitchen in the community seems almost nonexistent, except when the statistics actually begin pouring in; Open Heart Kitchen, the largest hot-meal program in the Tri-Valley, announced that they have consistently served over 300,000 meals in recent years, with the number further increasing to over 365,000 in 2016, a number completely contradictory to residents’ perspective on the area’s supposed affluence. So the question remains: how could the appearance of poverty levels and the reality be so at odds with each other?

Clare Gomes, the Operations Director at Open Heart Kitchen, explains, “That’s the thing — it’s hidden poverty. People think of the Tri-Valley as being a very affluent community and while that’s true, there’s also just as much poverty. There’s probably a little bit of thought process [within residents] that ‘it’s not in my neighborhood,’ and people don’t want to acknowledge that there is a problem.”

Founded in 1995 by a woman who provided soup once a week to the homeless population in Livermore, Open Heart Kitchen sought to counter this “out of sight, out of mind” mentality and help those in need overcome the shame of asking for help. Their relative success is shown in the venture’s expansion to provide three distinct meal programs — The Hot Meal Program, Children’s Weekend Bagged Lunch Program and the Senior Meal Program — at four separate locations throughout the valley.

When asked about how the recipients of the program changed with the times, Gomes elaborated: “We do get the homeless there, but we also do get single moms, single dads, seniors, veterans, the unemployed, the underemployed, grandparents raising their children. It is an amazing gamut of population that we serve. All cultures, all ages.’’

Such a change wasn’t accomplished simply by food. In fact, Open Heart Kitchen’s appeal lies arguably in its quintessentially unlike-a-soup-kitchen experience.

Newly appointed Executive Director Heather Greaux, explains, “It’s a matter of welcoming them as if they were a guest in your restaurant and not considering it a soup kitchen where you’re providing them a service for free. I think it’s important to treat people with respect, the same respect you’d give someone paying for a meal.”

Gomes adds, “One of the big things that’s important to us is providing a safe, respectful, dignified site for people to come and get fed.”

This focus transcends into creating a sort of social haven, especially for senior recipients, who are provided opportunities for regular interaction. Volunteers work to make the kitchen’s environment hospitable with their proactive attitude; Greaux recollects an incident where “I went to one of our sites, and there was a homeless woman and her kids; one of them didn’t have socks, and so someone came up to me and said, ‘Gosh, they don’t have any socks. What are we going to do?’ And then one of my employees came up with the socks, and I realized that she had already been out and found the socks for the child. It just showed me that she recognized the problem right away, without even being asked, and got what this family needed.”

While Open Heart Kitchen’s efforts are laudable, its increased relevance in the community signals a troubling development; as the area continues to develop, those previously safely situated in the middle class are struggling to stave off homelessness, with many quick to point fingers at the rocketing rates of house prices in the area. The East Bay has faced an influx of high-earning families from Silicon Valley, who were attracted to its (relative) affordability compared to cities like San Francisco, short commuting distances to tech hubs in the region and extremely well-rated schools. According to analysis by the Paragon Real Estate Group, the median house sale prices in the Tri-Valley more than doubled from slightly over $400,000 in 2001 to $913,500 in 2017, a dramatic increase also reflected in rent rates, which have outpaced the rest of the Bay Area. Many individuals now “struggle to keep their home and pay their bills and feed their children. There are more people than we realize in this community that are choosing between food and utilities, food and rent: they’re always having to cut back on something, so it’s important for organizations like ours to be in place to provide safety nets,” Greaux further explains.

Among those affected by the skyrocketing housing prices are children, who have to rely on non-profit programs or reduced school lunches for proper nutrition. Open Heart Kitchen’s Children’s Weekend Bagged Lunch helps almost 2400 students at 25 different locations tide over the weekend, an astronomical figure boosted by the recent increase of schools signing up and increasing the number of meals delivered to their students.

Housing and hunger go hand in hand, and as the wealthy continue to flock to the Tri-Valley, these problems appear to have no definite solution. But while poverty continues to be exacerbated, soup kitchens promise to adjust and fit the need of the community.

Gomes mentions, “what’s most rewarding is when someone has come to us in a time of need and they’ve gotten meals from us for a couple of months … then we don’t see them for a while and then they come back to us and then they tell us, ‘I have a job, I’m back on my feet and I was able to pay my bills because you provided me food and I didn’t have to spend my money on food that I could spend on my bills and rent,’ and now they’re self-sufficient and stabilized and for them to come back to us and say I was able to do it because of you. To me, there’s a success story.’’