America has always been referred to as “a nation of immigrants,” with the country being mainly composed of immigrants and their descendants. Although U.S. history is a confusing duality soaked in both violence and hope, one where we have both been welcomed and expelled, the statement holds true. Yet, the subject of immigrants themselves remains one of the most fragile social issues of our times. To assimilate, or not to assimilate, is the question that has long divided America, with no apparent solution. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t a better alternative: integration.

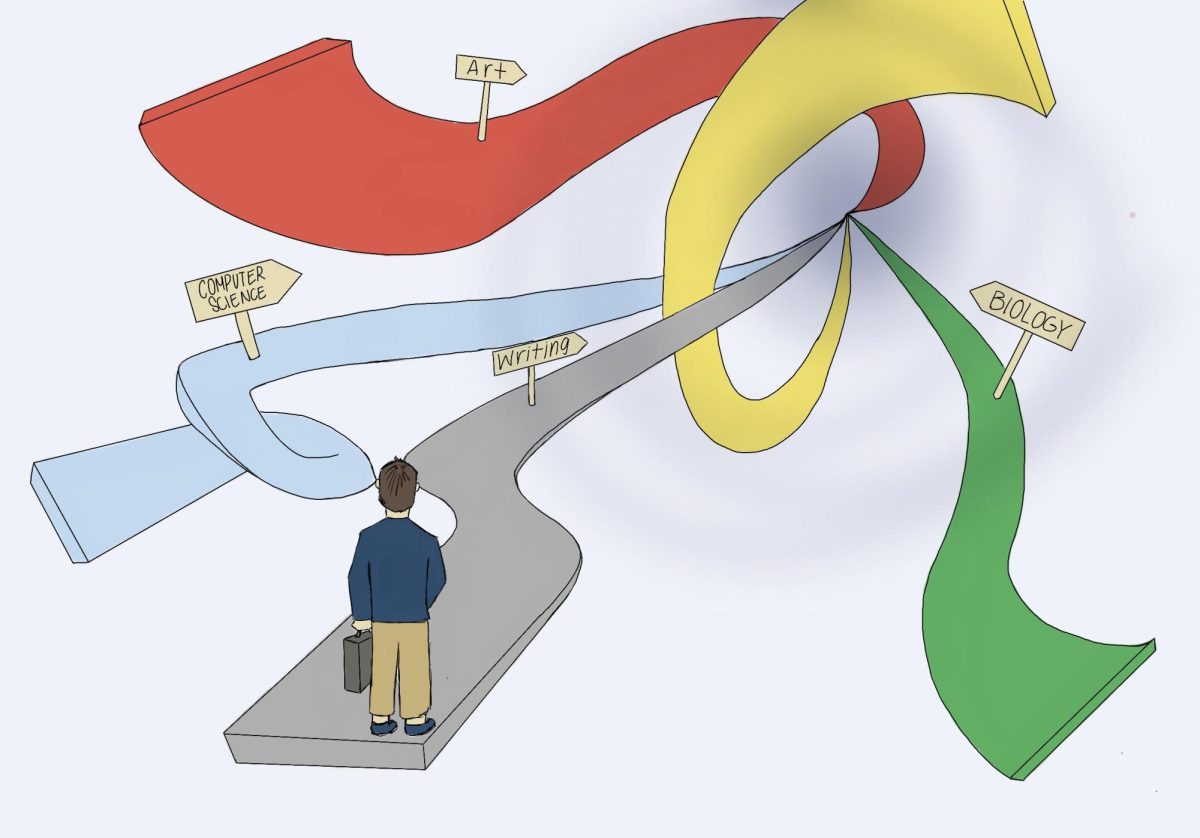

Ultimately, the purpose of both integration and assimilation is to help immigrants settle successfully into their new homes. However, the paths taken to reach that end goal are by no means the same. Assimilation is essentially the erasure of someone’s culture. Integration, on the other hand, is a form of participation that allows immigrants to retain the cultural habits and values they hold close to their hearts.

Even though America is the land of the free, when many of us isolate ourselves in our own cultural bubbles, mingling with only those from the same home country does more harm than good.

For instance, in the mid-19th century, large numbers of immigrants from China formed immigrant communities in America, interacting with only other Chinese people who spoke their native languages. There is, of course, nothing inherently wrong with building a haven among the people you feel you most identify with, but it is also important to note that their descendants generally interacted far less with mainstream American society. Out of the 14,500 people living in San Francisco’s Chinatown today, a vast 71% of the population does not speak English proficiently.

But is this really a bad thing? Well, for one, the younger generation will likely be exposed to far fewer opportunities than they might have otherwise. Hindered access to cultural exchange may limit the development of crucial skill sets, making upward social mobility even more challenging. Even today, Chinese immigrants still congregate there because of language barriers, which, in the long run, restricts their ability to interact with the broader society.

We can’t overlook the fact that Chinatown’s history is deeply rooted in decades of racial discrimination. Early immigrants banded together to create a safe haven where they could thrive without fear of anti-Asian violence. Chinatown is a cultural hub rich in heritage, but at the same time, the neighborhood undermines the needs of its people to build connections with those outside of their haven. Perpetual isolation will eventually erode bridges that can’t be rebuilt.

My own grandmother has seen the benefits of integration. In the 1990s, she left Nanjing, China, choosing to move to a small city in Oklahoma. Life as an immigrant was hard and unfamiliar at first, but she quickly adapted to her surroundings. She learned English, found a self-sufficient job and sent her daughters to school, gradually integrating into American society. Eventually, my grandmother moved, settling happily in a hard-earned home on the East Coast. Integration not only helped her survive but also thrive.

Her story reflects a larger trend: Research shows that the economic gap between immigrants and the native population tends to shrink over time. As my grandmother did, when immigrants acquire proficiency in the host country’s language, pursue further education and build social connections, they are better able to access and pursue greater opportunities, benefiting both immigrants and their host countries. Integration directly opens the door to these opportunities, allowing immigrants to preserve their cultural heritage while also participating in the community.

My intention is not to place all the responsibilities on immigrants themselves, but to somehow find a middle ground. Integration is obviously a two-way street: If there is no one to speak to, you can’t learn a language. My point is to take the best of both worlds and foster an environment where both sides can mutually grow and thrive together. For immigrants, social integration means developing a true sense of belonging within their host society. Equally important is the role of the native population. Integration can only happen when natives fully embrace them as genuine members of society.

It might seem like an impossible task, with differing metrics to determine integration and diverging opinions on what “best practices” should be kept. Think of it not as a checklist but as a potluck: one where everyone takes a step outside of their little bubbles and into the dining room, bringing plates of their favorite cultural foods before finally sitting down altogether to share a meal. That is the beauty of integration.