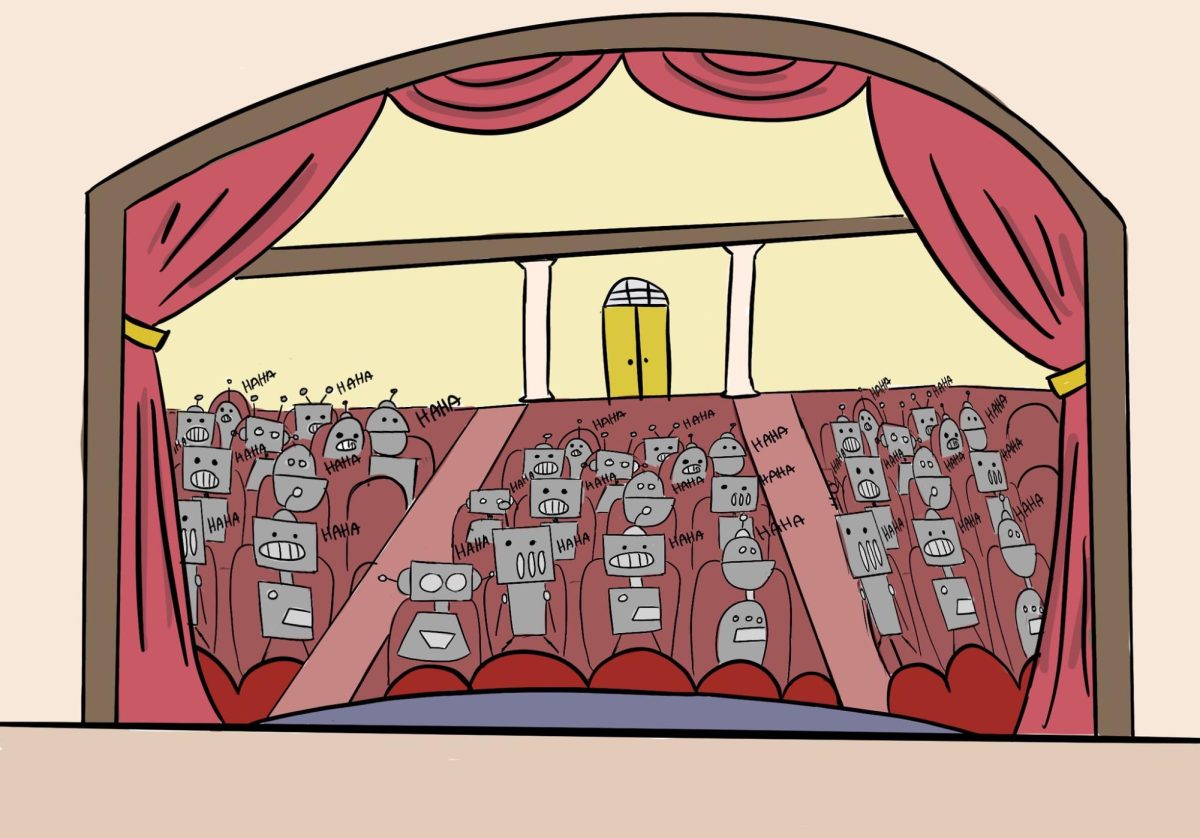

The most hated sound on television, or the industry’s best secret? The laugh track, recorded laughter added to a TV program to enhance the comedic experience, was a staple in comedy shows and sitcoms in the 2000s. However, it has all but vanished from modern television — and for good reason.

In 1966, almost every comedy on air was filmed in front of a studio audience, or at least producers pretended that they were. Shows like “The Andy Griffith Show,” “The Beverly Hillbillies” and “Green Acres” all used laugh tracks, but few viewers knew of the extent of the artifice behind this laughter. Many viewers feel like shows try to convince the audience that they are funny through laugh tracks. Furthermore, removing the laugh track exposes how superfluous canned laughter really is; actors have to leave a pause for audience reactions, resulting in overexaggerated facial expressions. Worse, laugh tracks are often so overused that they dilute good jokes — they’re like the boy who cried laugh — when the laugh tracks keep telling you to laugh when nothing’s funny, you don’t recognize the genuinely funny jokes.

Before television, live operas, ballets and comedy shows were the most common form of entertainment, where one could experience audience reactions in real time. Laugh tracks originated with radio shows, the first form of broadcast media, when American families would gather in their living rooms to enjoy entertainment. Studios used laugh tracks to give people the live experience at home and to convince audiences that their jokes were, in fact, funny. When single-camera TV shows came up, each scene had to be filmed from multiple angles, and this caused the live laughter to sound inconsistent as it was coming from different angles.

Additionally, audience laughter was simply unreliable; sometimes it was too loud, too long or they would laugh at the wrong time. To fix this issue, CBS sound engineer Charley Douglass started to “sweeten” the audience’s recorded laughter so it would perfectly fit the scene. “Sweetening” in the context of television is the usage of laugh tracks to enhance the laughter of a live studio audience. He would insert a laugh track after jokes that didn’t receive authentic laughter. Douglass even invented a physical “laff box” that held slots for 32 reels with 10 laughs each. It was called the “Audience Response Duplicator,” and could hold 320 laughs at most, producing different types of laughter. The Laff Box was patented and only available to Douglass, so throughout the 1950s, Douglass monopolized laugh tracks on television.

It took another couple of decades for other sound engineers to figure out how to use canned laughter, with widespread usage beginning in the 1970s. Ever since then, laugh tracks have become a staple in American comedies, even after multi-camera shots were introduced. Until the early 2000s, nearly every major show relied on a laugh track: “Friends,” “Drake & Josh,” “How I Met Your Mother,” “Big Bang Theory,” “Everybody Loves Raymond” and more — so much so that it’s become a hallmark in American TV. When sweetening became software, it also took a softer role and slowly began to go out of fashion. “The Big Bang Theory,” ending in 2019, was one of the last shows to utilize canned laughter before its demise.

So why has the laugh track disappeared almost completely from TV? Dead air on television was a taboo to be avoided at all costs. This was until the ‘90s, when single-camera comedies proved to be successful without the use of canned laughter, notably with HBO’s “Dream On” and “The Larry Sanders Show.” Other studios began to follow this method, leading to shows like “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” “Malcolm in the Middle,” “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia,” “Parks and Recreation” and more. The shift to comedies without canned laughter led studios to explore character development and focus on the plot more instead of saturating them with punchlines. It also allowed directors to explore the balance between humor and genuine stories in a TV show, so it could be more than just a comedy. Shows like “Arrested Development,” “The Office” and “30 Rock” give more importance to the jokes rather than the audience’s reaction. The result of not losing out on precious minutes due to laugh tracks is higher quality, funnier episodes.

Laugh tracks are still hanging on by a thread, and it won’t be long before we look back at them and wonder why they were ever used. Over time, audiences have grown distrustful of canned laughter, with many YouTube videos showcasing popular sitcoms with the laugh tracks removed. These videos expose the robotic and soulless nature of shows like “Friends,” unveiling not only the profound impact of the laugh tracks on an audience’s reaction but also the poor quality of the jokes. Straightforward comedies with constant, shallow punchlines are always there if you’re ever in the mood to laugh at something mindlessly. It’s hard to deny the influence of the laugh track as one of the greatest innovations of the television industry; at one point, it was hard to envision a TV sitcom without canned laughter. However, whether it’s for the better or worse, the downfall of canned laughter is a clear indication of the evolution of pop culture and the change in audience attitudes that comes with innovation.